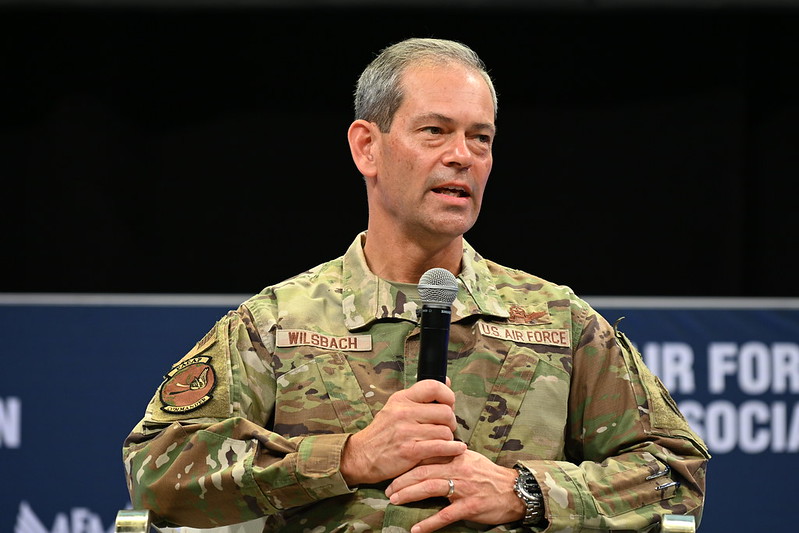

The Air Force is proposing a large budget investment in pre-positioned equipment to lay the groundwork for its agile combat employment concept, which calls for USAF forces to be widely dispersed and frequently moving to complicate enemy targeting, Pacific Air Forces commander Gen. Kenneth S. Wilsbach reported.

He also forecast a major investment in uncrewed and “attritable” aircraft and decoys, both to bolster USAF capacity and to present an enemy with a large number of must-shoot targets that would rapidly draw down enemy magazines; and pitched for cargo UAVs to provide logistics support to far-flung ACE operating locations.

“There’s quite a bit of money in the [fiscal year] ’23 budget, when we finally get to start pre-positioning equipment, and parts, supplies, food and water, fuel, those kind of things,” Wilsbach said during a March 14 Mitchell Institute webcast. This will alleviate an excessive demand on airlift, he said, because “if you pre-position those things, at least initially, [those are] places that you don’t have to have airlift going in, immediately supplying parts and supplies, etc. So, we’re going to have very robust pre-positioning at numerous locations around the theater.”

The ACE concept of employment was published in December and tells wing commanders how to “train to it every day” and how the concept will be implemented in PACAF and U.S. Air Forces Europe; and “what the expectations will be,” he said. “That document has been instrumental in allowing everybody to get ready and be able to win when you get there.”

In the recent Cope North exercise out of Guam, ACE concepts were employed at 10 different operating locations, incorporating several countries, he said. The exercise “moved those assets around … on a daily basis,” and they were commanded and controlled at the same time.

Japan and Australia are both keenly interested in developing their own compatible versions of ACE, he said, “particularly the Japanese, who are really trying to expand their envelope and ACE … on mainland Japan. So that’s really exciting for us, because we intend to do ACE with them, if we ever have to.” Australia is doing similar things, and is a “great partner” in the concept.

The two enabling concepts for ACE are logistics and command and control, he said, because of the “contested environment.”

There won’t be enough C-17s to go around to service all the operating locations, he said, meaning C-130s will carry a greater share of the burden. That makes sense because exercises so far have found that most of the airlift required is to carry small, line-replaceable unit parts and other objects the size of a jet engine or smaller.

“If we’re relying on the C-17 fleet to do this, we’ll run out of C-17s very quickly,” he said, especially since the strategic transports will probably be needed for noncombatant evacuation operations and to move forces into the theater. There aren’t enough C-17s even when the C-17s of allies are added to the mix.

“And you would waste the capability because, like I said, often it’s just a line replaceable unit that has to go out to an island somewhere, and you don’t need a whole C-17 to take a piece that big. So, C-130s will be a big factor in this.” A C-130 squadron at Yokota Air Base, Japan, is “frequently [doing] ACE iterations, and … they participate in the exercises as well.”

Wilsbach said he’s been “advocating for a few years for something even smaller than a C-130” that could take a person or an engine or a few parts.

“Perhaps it might even be an unmanned vehicle … but have a lot of them,” he said.

The concept is similar to the C-47s of World War II, he explained.

“There were … thousands, maybe, of C-47s, and they were all over the Pacific. And they weren’t fast, but they can carry a lot, and they tackled the logistics problem of the Pacific by having a lot of tails to … move equipment.” Although “it got there at 120, maybe 150 knots … it worked. We could have something like that for ACE, where you don’t have to have it going 500 knots,” but the logistics effort wouldn’t “eat a lot of tail numbers to be able to get the small bits of equipment and pieces to the various spots that we intend to deploy from.”

The flip side of the ACE coin is communications, Wilsbach said, calling it “pretty difficult to do” and fragile because lines of communication can be cut.

“What I’ve been asking for—and what we’re working on and approving—is a meshed, rather than network,” model, he said. He made the analogy to the human brain, which, if injured, “figures it out and finds different paths” to move messages and information around, and heal itself.

“It just happens,” he said, and with artificial intelligence and machine learning, the same will be true of the communications system the Air Force is now building for ACE.

“We want it to be self-healing so that operators aren’t working the comm gear, they’re operating and [figuring] out how to create airpower effects and executing those airpower effects, not switching frequencies and figuring out where the comm could go through.”

Wilsbach said that “if you tackle those two things—logistics and communications—ACE becomes a little more easy. It’ll still be difficult, but it’ll be easier than if we struggle with those two aspects.”

More UAVs Needed

Uncrewed aircraft will also be critical to the fight, Wilsbach said.

China’s ability to defend itself is “very robust” because of its elaborate anti-access/area denial air defense systems, he noted. The only way to “stress” those defenses is with large numbers of attritable aircraft, he said.

“What I would advocate for is to make the manned aircraft ‘exquisite’” in their capabilities “and the uninhabited aircraft … less exquisite, slightly more attritable, so that we can have more of them,” he said.

China would have to target decoys or unmanned aircraft coming toward it “because they’re not exactly sure” what those platforms are, he said, and “they’ll shoot weapons at [them] and use up their weapons.” Employing such swarmed, massed aircraft “could give you an advantage because [China would] use up their resources, shooting things that you don’t care that they shoot down. So that would be a capacity that I’m very interested in, as we go into the future.”

Not all of these unmanned aircraft should be stealthy, he said; otherwise, China would not see them and use up weapons against them.

“You give them a lot more targets to defend against,” he said. The Chinese would ignore these aircraft at their peril, because they would be equipped with sensors and weapons that could penetrate and destroy Chinese assets.

“All of these assets will have some kind of capability, whether it be a sensor … weapon truck, jammer … and they should swarm as well, so they should talk to one another and collaborate not only amongst themselves, but also with the manned platform that they’re supporting,” Wilsbach said. All this will present China with “many more dilemmas than they can handle at any given time. And what we’ve seen in exercises is, when you amass the effects, and we amass the number of weapons that are going after a particular target, they’ll be able to shoot down some—because as I’ve said, they have really good defenses—but they won’t be able to shoot them all down. And it’s the weapon that creates the final effect that you’re looking for that counts.”