The Air Force and Navy’s logistics capabilities—including airlift and aerial tanking—are insufficient for the needs of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, its commander told lawmakers last week, and the requirement needs to be addressed by more than just commercial stopgaps. He also endorsed the idea of small, uncrewed sustainment craft, as they could permit support to smaller and more dispersed units.

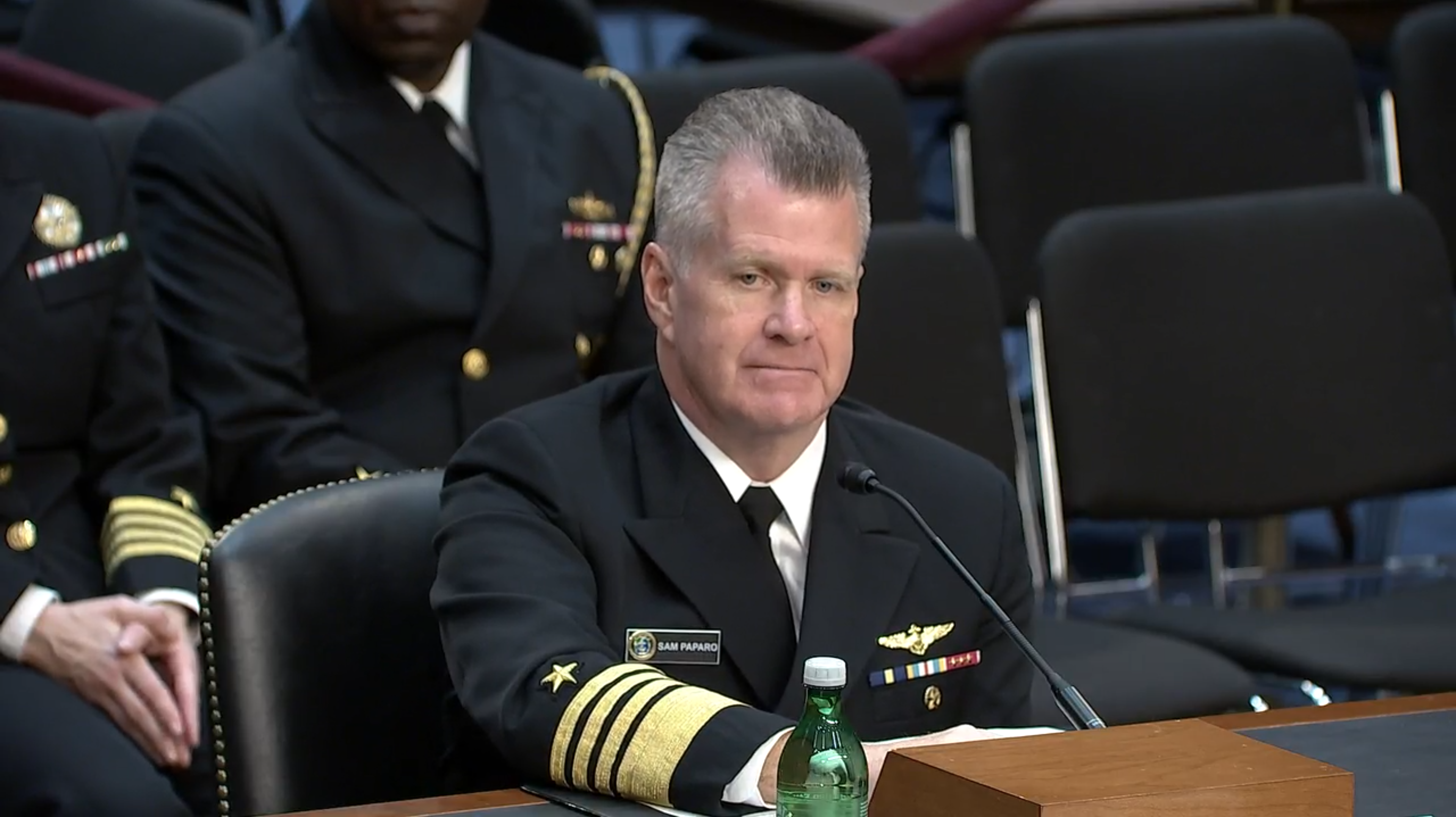

“We have … significant gaps in sealift,” Adm. Samuel J. Paparo told the Senate Armed Services Committee in an April 10 hearing, adding that the Combat Logistics Force—which includes both sealift and airlift—“in total is about 60 percent of the actual requirement.”

INDOPACOM makes up for that in part by hiring commercial tankers and “contracting other capabilities,” he said, but “when the unforgiving hour comes” and battle is engaged, only military ships and aircraft will be able to go forward into combat zones, he noted.

Moreover, “as I utter these words, 17 of those Combat Logistics Force ships are laid up for lack of manpower,” Paparo noted.

In addition, Paparo said, “we have to have many millions of pounds of jet fuel in the air for every capability. And so our tanker fleet is below what we need. We account for that with some contract air services as well.” U.S. fighter jets refueled off a commercial tanker in late 2023 over the Indo-Pacific, and Air Mobility Command has said it is working on an analysis into expanding the concept.

Still, Paparo noted the same issue: should conflict arise, the U.S. military will need its own aircraft to send into war zones.

To highlight the massive burden on airlift, Paparo said that moving a single Patriot air defense battalion from INDOPACOM to the U.S. Central Command area of responsibility “took 73 C-17 loads” to accomplish.

“That’s [just] one battalion of a force element,” he emphasized. “So our lift requirements must be paid attention to.”

On social media, former AMC commander Gen. Mike Minihan echoed Paparo’s point: “If [73] tails are required for a limited move like that, we are woefully unprepared for what large-scale operations against a peer adversary will demand,” he wrote.

To get after these shortages, Paparo said that “diversifying the tanker fleet is key,” as are “alternatives of lift capability that we can order into harm’s way.”

Asked by Sen. Rick Scott (R-Fla.) if he sees a role for uncrewed commercial airlift “in a contested logistics environment,” Paparo said it would open the door to new tactics.

“One of the precepts of unmanned is, never send a human being to do something that a machine can do,” Paparo said. “So … inherently, we’re moving in that direction, and I’d welcome the ability to execute that lift.”

He also said such a capability would “give me the ability to diversify the places” that sustainment can go directly, “bringing smaller payloads into simultaneously smaller maneuvering units, and would enhance our ability to sustain by the speed it would confer.”

Paparo also said the command is doing everything it can to smartly manage the logistics support, materiel, and pre-positioning of items it has.

“Over the top of all of this, we’re incorporating artificial intelligence tools with command and control tools, so that it’s not an on-demand system, but so that we are executing that absolutely indispensable joint function as effectively as we possibly can,” Paparo said.

“We are an AI-enabled headquarters, and that’s important too, but you can’t AI your way out of a materiel shortage.”