The Space Force’s first rapid satellite launch was so nice, it’s next goal is to do it twice.

Space Systems Command and the Defense Innovation Unit awarded two contracts for the Space Force’s next tactically responsive space mission, dubbed Victus Haze. The deals, announced April 11, go to True Anomaly of Centennial, Colo., and Rocket Lab of Long Beach, Calif.

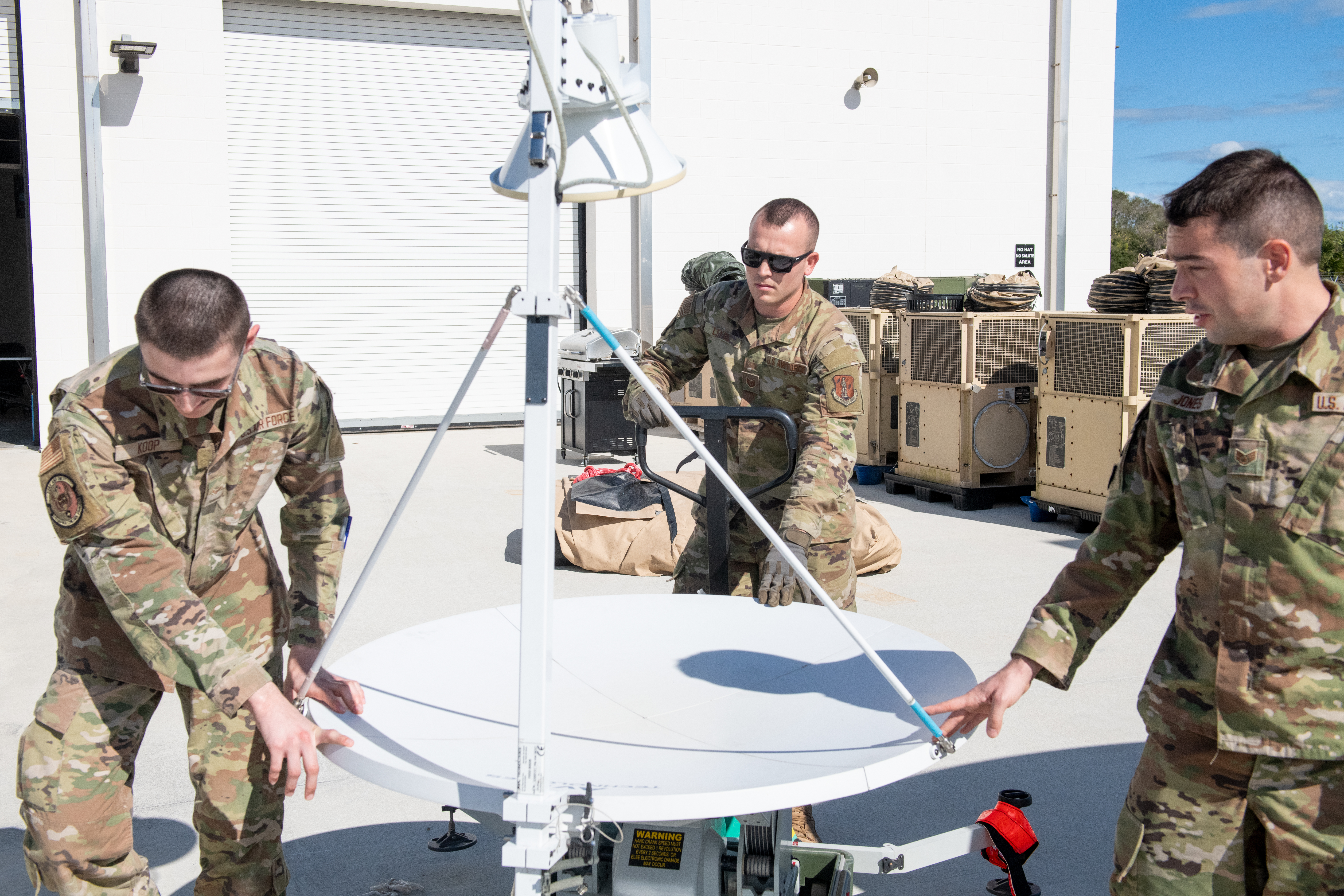

Each company will build a satellite and a command and control center for rendezvous and proximity operations by fall 2025. After that, the spacecraft will go through a series of steps to prepare for launch.

True Anomaly’s bird will launch from either Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Fla., or Vandenberg Space Force Base, Calif., on a “rapid rideshare” rocket, according to an SSC statement—presumably a SpaceX vehicle. Rocket Lab will launch its own satellite using its Electron rocket, either from either Mahia, New Zealand, or Wallops Island, Va.

“While this is a coordinated demonstration, each vendor will be given unique launch and mission profiles,” SSC announced.

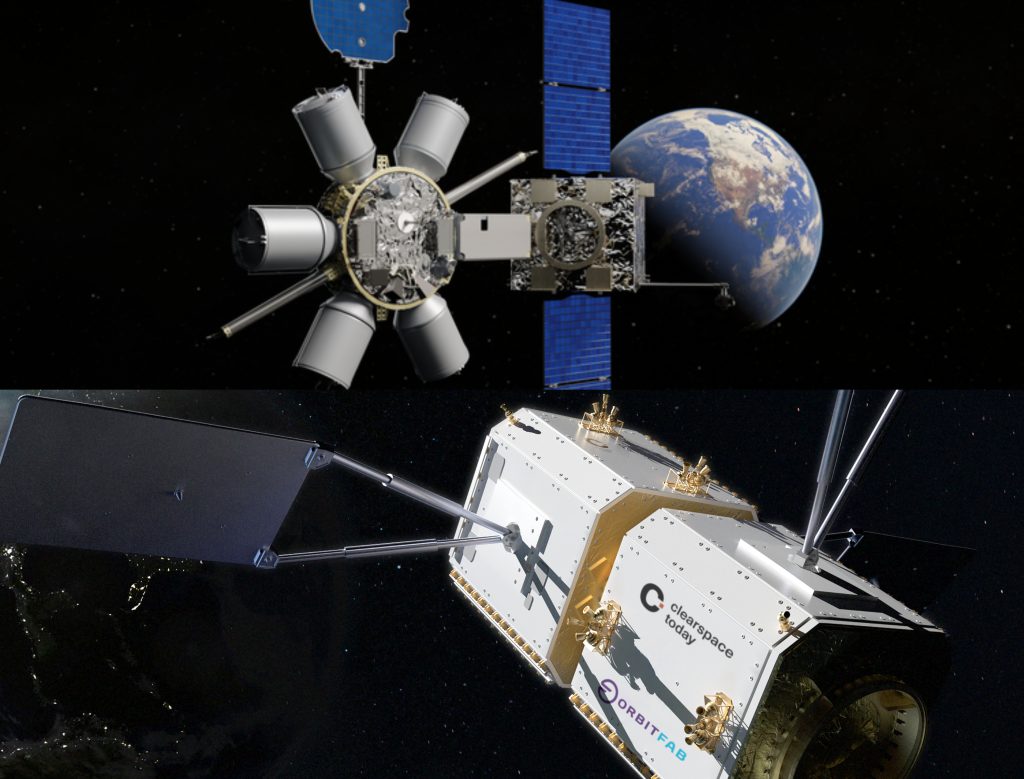

Once in orbit, the two spacecraft must demonstrate “dynamic space operations,” maneuvering in orbit and performing domain awareness work.

The Space Force is sharing the cost of the True Anomaly satellite, with USSF’s SpaceWERX innovation arm each contributing $30 million to the project. Funding for the Rocket Lab contract, valued at $32 million, comes through the Pentagon’s Defense Innovation Unit, whose mission is to help the Pentagon embrace and field new technologies faster. SSC’s Space Safari program office will provide programmatic oversight and execute the mission for both satellites.

“It’s an honor to be selected by the Space Systems Command to partner in delivering the VICTUS HAZE mission and demonstrate the kind of advanced tactically responsive capabilities critical to evolving national security needs,” Rocket Lab founder and CEO Peter Beck said in a statement.

“The space domain is one of the most challenging environments in which to test and train, and we applaud the service and Congress for their dedication to the TacRS mission set, which is increasingly necessary for deterrence, space domain awareness, and dynamic space operations,” said True Anomaly CEO and cofounder Even Rogers in a statement.

The Space Force hinted at conduding a double demonstration in its 2025 budget request, noting that Victus Haze would include “multiple mission components.” Following Victus Haze, the Space Force wants to “provide initial operational capabilities” for tactically responsive space, the budget documents say.

TacRS seeks to ensure the Space Force can launch satellites and get them into orbit and operational in a crisis or as a new tactical requirement emerges. The whole idea is to “demonstrate, under operationally realistic conditions, our ability to respond to irresponsible behavior on orbit,” said Col. Bryon McClain, SSC’s program executive officer for Space Domain Awareness and Combat Power, in a statement.

Victus Nox, the first TacRS demonstration, set out to prove the Space Force and its industry partner, Millennium Space Systems, could build a satellite in 12 months, enter a “hot standby phase” as contractors waited for an alert notification, then launch. That test worked: After receiving the alert, the satellite was transported 165 miles, tested, fueled, and mated it to the launch vehicle, all in just 58 hours. After that, the team went back on alert, waiting for final launch orders and orbital parameters. Once those came in, the satellite launched in 27 hours in September 2023.

Chief of Space Operations Gen. B. Chance Saltzman has repeatedly cited that success with pride—and a clear warning that Victus Haze must go even faster.

“I still think we have margin in the schedule,” Saltzman said earlier this year. “And so in Victus Haze, we’re going to set some standards that say nope, we’ve got to compress this more. Five days from warehouse to on-orbit operations is pretty fast. But in the grand scheme of things, when you’re moving at 17,500 miles per hour, five days is still a long time, and a lot can happen in five days. And so I’m going to be pressing the team to continue to reduce that critical path down to hours and hours and hours, rather than days.”

Space Force officials have noted the demonstrations have also shown the service how it can cut down on bureaucratic processes and move faster when needed.

More TacRS demonstrations are in the works. Budget documents cite a third mission, Victus Sol, envisioned to launch in late 2025 or early 2026, and a fourth mission is envisioned to get underway sometime in fiscal 2025.