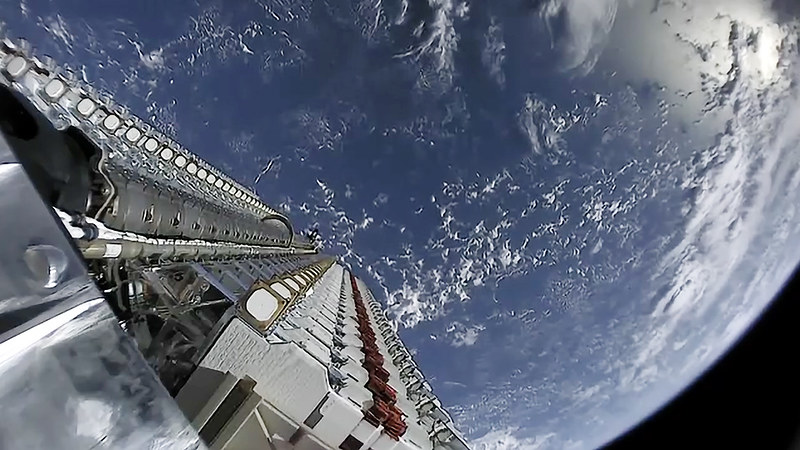

The rapid proliferation of commercial satellites is revealing increased potential for counter-satellite military operations and collateral damage.

SpaceX reported that its Starlink satellite internet service was jammed in Ukraine after the start of the war, and Viasat reported hackers attacking its satellite internet service there around the same time. In the wake of Russia’s debris-generating test of a ground-launched anti-satellite weapon in November 2021, operators with satellites in low Earth orbit saw risks increase as more than 1,500 new pieces of debris were scattered in that region.

The Russian act intensified calls to establish norms of acceptable behavior in space, and the U.S. government pledged not to perform any future debris-generating tests in space.

To help inform efforts to establish norms, the not-for-profit Aerospace Corporation’s Center for Space Policy and Strategy studied other areas where civil and military activities converge. The study, “Commercial Normentum: Space Security Challenges, Commercial Actors, and Norms of Behavior,” published Aug. 23, notes that commercial satellites could make attractive targets in a space war and suggests that commercial operators should be involved in the issues raised as a result. The paper lists factors for companies to weigh when deciding whether to take an active role in establishing norms and ideas for how they might do so.

Aerospace’s Robin Dickey, the report’s author, writes that commercial participation in establishing security norms could be more important in space than in other domains because “the physics of debris propagation in space make it much harder to limit the effects of any single accident or conflict.”

Adding to the complexity and risk is the emerging intermingling of civil and military uses of satellite assets. The Space Force is increasingly interested in incorporating commercial constellations and data into its activities, both as a means to extend situational awareness and to ensure resilience in space in the future. Chief of Space Operations Gen. John W. “Jay” Raymond has called America’s and allied space industries a “great advantage” and said the Space Force must harness and leverage the “explosion of business that’s going on.” Commander of U.S. Space Command Army Gen. James H. Dickinson has said he is most interested in how commercial space firms can improve space domain awareness.

The risk, both to commercial entities and the U.S. military, is how military uses for those systems could turn them into legitimate military targets. “Were conflict to significantly escalate in space, the potential lack of distinction between military and commercial satellites could result in targeting of even commercial satellites that do not provide military services,” Dickey writes. Because they’re uncrewed, commercial satellites could also be seen as lower-threshold targets, making their destruction “less escalatory” than attacking crewed assets in other domains.

Dickey draws comparisons with past instances in which militaries targeted civilian property, organizing them into three categories:

- Collateral damage from attacks on military objectives. Landmines roughly equate to how ASATs scatter destructive debris. The International Space Station provides an example of how the debris affects satellites: NASA’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel reported in July that out of 681 conjunction notifications the ISS crew had received in 2022, to warn of closely approaching objects, 505 traced back to the Russian ASAT test.

- Attacks due to misidentification or misinterpretation of a commercial activity. At least six commercial airliners were shot down before clear norms were established for mitigating against such commercial targets in the midst of combat.

- Deliberate targeting in war. Historically, commercial maritime shipping has been targeted during military conflict, justified because such ships either carried legitimately targeted supplies or helped support military activity economically. In space, deliberate jamming, cyberattacks, or the “disruption of sensors” with directed energy could similarly apply pressure to commercial activities.

Dickey makes the case, in part, that because companies have a stake in space security, they should also get a say in establishing the security-related norms that might otherwise seem like the purview of governments.

But because norms will only work to deter bad behavior according to the extent that they’re accepted around the world, Dickey concedes that they may prove most useful in justifying a response—“providing a legal of political point around which other space actors can rally if a state goes rogue.”

Practices such as establishing minimum cybersecurity standards for satellites; transparently sharing mission data between the commercial sector and governments—even competing ones; and implementing formal lines of communication in case of problems all could help protect satellites and avert disaster.

Dickey’s paper proposes three styles of approaches to consider:

- Protect all civilian/commercial assets. In this circumstance, any attack on commercial assets would be ruled out, regardless of the satellite’s purpose. Determining what constitutes an attack would also be necessary. “Are commercial satellites that sell services to militaries viable objectives?”

- Protect all essential space services. In this approach, only certain kinds of services would be protected. The risk is that this plan would “exclude numerous commercial satellites from the highest degree of normative protection.” But it could get closer to legal and political common ground.

- Protect only those commercial satellites that do not provide military services. This could be done by conveying to other countries “intentions and activities to de-escalate misunderstandings.”

Establishing normative behavior does not assure that satellites will never fall prey to military attack or collateral damage, Dickey notes. Norms “should not be the only approach to mitigating potential threats. However, they can be an important piece of the larger puzzle.”