The ability to achieve air superiority and control airspace over a war zone is a key U.S. military strategy, and in some cases has been the primary means of achieving military objectives, such as when NATO intervened to stop Serbia’s war in Kosovo and the counter-ISIS campaign in Syria. But in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Russia’s failure to control the skies has provided a back-to-the-future moment highlighting the critical value of air power.

Russia’s air force is the second largest in the world, but has proven incapable of achieving air superiority against a much smaller foe. Ukraine has cleverly deployed air defenses, including shoot-and-scoot S-300 mobile systems and using man-portable Stinger missiles to attack low-flying aircraft seeking to evade air defense radar. Now, with the battle shifted to the vast expanse of eastern and southern Ukraine, it has become an artillery and infantry war.

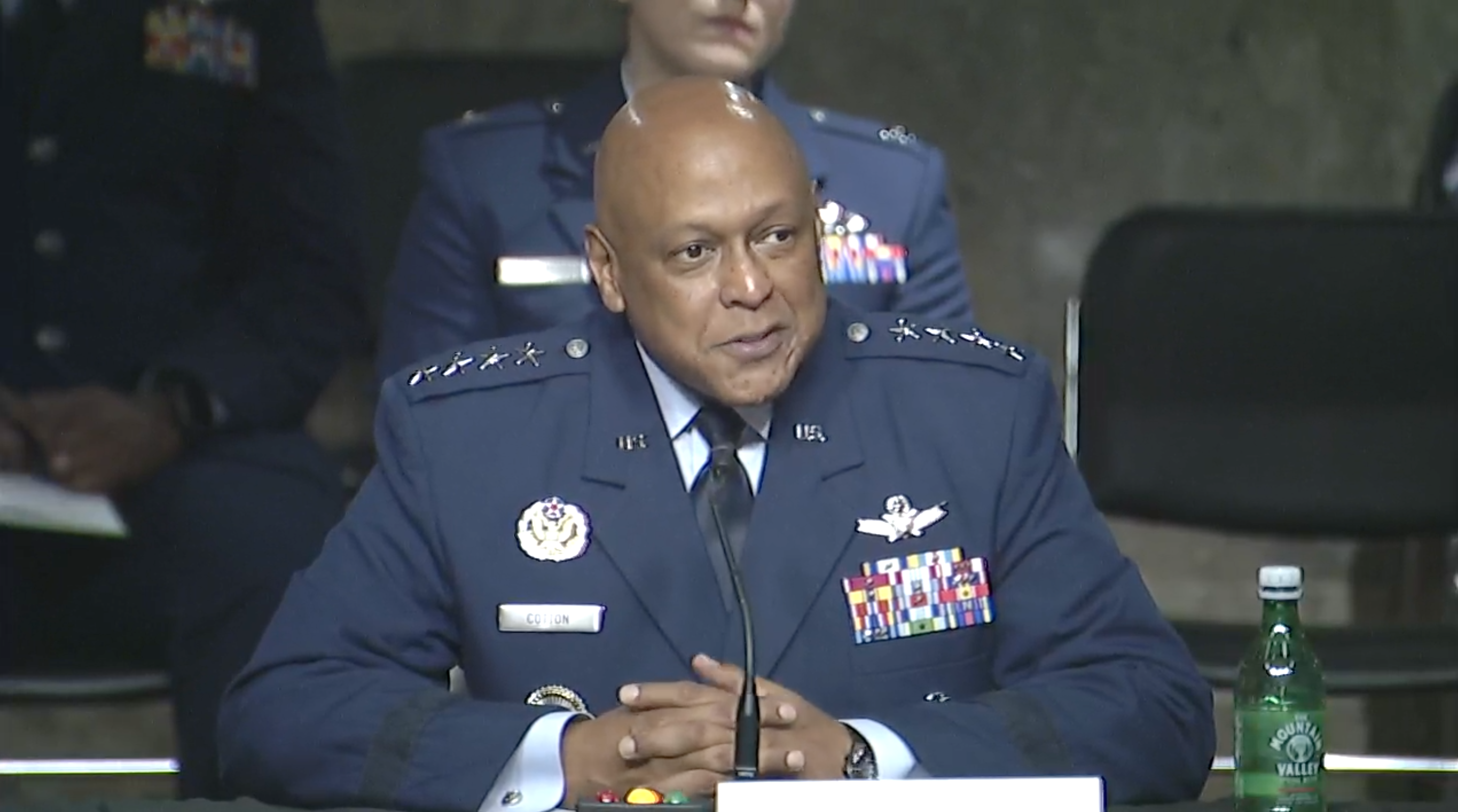

“Neither side has air superiority,” said Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr. at the International Air Chiefs Conference in Washington, D.C., on Sept. 16. “It’s turning into a complete land war, including with artillery. You can almost harken back to [a] World War I type of warfare, where it’s just moving things back and forth.”

The role of air power continues to be the subject of debate. Advanced, large air forces have rarely interacted, even in war. In Syria, where the U.S. and Russians are engaged in missions in support of different sides of the conflict, the two air forces operate a deconfliction line which is used daily, Ninth Air Force commander Lt. Gen. Alexus G. Grynkewich confirmed to Air & Space Forces Magazine.

In Ukraine, Ukraine is employing Turkish-made Bayraktar and off-the-shelf commercial drones to combat Russian armor, but not to police the sky. They are better suited to the kinds of roles aircraft were used for in WWI, such as reconnaissance and artillery spotting.

Russia’s inability to establish its will over a smaller nation has sparked some to question the conventional air superiority arguments, raising questions of how the U.S. would engage in a conflict against China, which like the United States, sees achieving air superiority as key to its military doctrine. Some commentators have even raised the heretical notion that air denial, rather than superiority, should be the objective.

“Typically, we think of superiority as a duality,” Lt. Gen. S. Clinton Hinote, deputy chief of staff for strategy, integration, and requirements, said Sept 6. “We are going to use the space, and we’re going to deny its use to others. The barriers to entry for denial, for denying the use of airspace, are much, much lower these days than the barriers to entry for extending control and keeping control of the airspace.”

Hinote said the U.S. Air Force must prepare for a conflict in which denial, not control, is the objective.

Brown’s take on the topic: “You’ve also got to think about the doctrine and how our Western air forces are operating,” Brown said. “We have freedom on how we operate as part of the planning team.”

Instead of demonstrating the need for fundamental rethinking, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has shown “the value of air power [and] what it could and can do,” Brown said. Experts argue Russia’s failures in Ukraine are more directly tied to its failure to employ airpower effectively than to its smaller rival’s prowess.

Editor’s note: This story was updated at 11:55 a.m. Eastern time Sept. 19 to clarify Brown’s remarks on denial of air superiority.