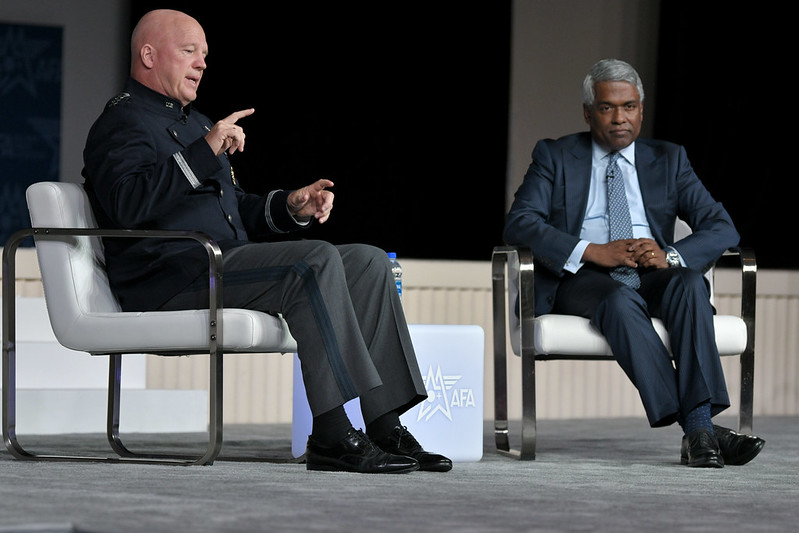

Gen. Mark D. Kelly, commander of Air Combat Command, delivered a keynote address on the “Air Force Fighter Enterprise” at AFA’s Air, Space & Cyber Conference, Sept. 21, 2022. Watch the video or read the transcript below. This transcript is made possible through the sponsorship of JobsOhio.

If your firewall blocks YouTube, try this alternative link instead.

Voiceover

Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome the Executive Vice President of the Air and Space Forces Association, Maj. Gen. Doug Raaberg.

Maj. Gen. Doug Raaberg

Good afternoon. Air Combat Command is the primary force provider of combat air power to America’s war fighting commands. ACC’s mission is to organize, train, and equip combat-ready Airmen to control and exploit the air on behalf of the Joint force. In short, be prepared to close the kill web.

To do that, ACC must accelerate change to grow an even more lethal, capable fighter force to defeat a peer threat. The commander of Air Combat Command is responsible for leading and paving the way for both the change in capability and the capacity to defeat the burgeoning threat from China and Russia. Ladies and gentlemen, please give a warm welcome to the commander of Air Combat Command, Gen. Mark Kelly.

Gen. Mark D. Kelly

Thanks. Well, good afternoon and welcome back from lunch. It’s great to be back here at AFA amidst fellow Airman friends and warriors and again, thanks to the Air Force Association for the opportunity to talk to you today about the Air fighter force, kind of where it’s been, where it’s at today, and where it’s going.

Last year, I got up here and talked about the Air Force’s ‘4+1’ fighter roadmap with the four being F-22 for air superiority, which needs to stay dominant until we can facilitate a hot handover with NGAD. The F-35 and the Block 4 capabilities that we need to penetrate adversary airspace and execute air defense take down. The F-15E and EX to provide the long-range big payload and disruptive fifth-gen sensors for day-to-day competition and homeland defense. And the F-16, which remains our capacity fighter for contested competition, homeland defense, and global force management and the plus 1, A-10, which has served our nation well but is severely limited in today’s world of increasing peer challenges.

Our fighter force has always faced and continues to face a mix of challenges and opportunities. Those challenges are presented by our adversaries, budget realities, political realities, global demands, technical aspects, and readiness equities. To get the correct fighter force mix, we have to engage all the enterprise dynamics at play.

Today, like yesterday, we need our fighter force to go further. We need to sense further in a more robust electromagnetic environment and we need to engage adversaries at long range. That engagement range, advanced sensors, and weapons requirement combined with operator proficiency and readiness defines high-end capability. And the hardest thing that an Air Force does, the hardest thing that an Air Force does, that helps define a nation’s combat power is maintenance and sustainment. While sustainment also contributes to an Air Force’s true capacity, it’s what I’ll focus on today. So why capacity?

First of all, capacity is not more important than high end capability like NGAD or advanced weapons like JDAM or advanced mid-band RF or long wave IR sensors. But the specifics of advanced platform sensors and weapons are difficult to discuss in open venue.

The other reason is capacity matters a lot. Capacity matters to our Joint force, which is organized, trained, equipped, operate with air superiority and not remotely, not remotely designed to operate without it. Capacity matters to our allies and partners who look to the United States to fulfill treaty obligations and lead coalitions. Capacity matters to our elected leaders charged to raise and support our forces and who provide direction and resourcing through the National Defense Authorization Act. Capacity matters to our strategic adversaries who are committed to winning the sensing battle, the readiness battle, the high end capability scrum and unquestionably, unquestionably defeat us with greater fighter capacities.

A bit about our capacity readiness and peer competition journey over the past three decades to review how we arrived at the present day. We deployed to Desert Shield, Desert Storm in 1990 with a portion of our 4,000 fighters that were organized, trained, equipped to fight the Soviet Union.

The Air Force went to Desert Storm with at least seven significant advantages over any other air force on the planet. We had an aircraft capability advantage. We had a fighter capacity advantage. We had an advanced sensor and weapons advantage, a combat readiness and warfighting credibility advantage. We had uncontested logistics, uninterrupted command and control, and adequate air base defense.

Thirty two years ago, our fighter capacity, combined with these other six attributes allowed us to deploy from around the globe without risking our ability to compete forward, our ability to respond to crisis without risk to our homeland defense requirements. Although Desert Storm technically ended on 28 February 1991, the Air Force fighter force, along with many of our fellow service and joint partners, never left the Middle East. But lacking a peer adversary, we significantly reduced the fighter capacity required to support that 24/7, 365 CENTCOM effort.

We continue the reduction in our fighter capacity through the ’90s and on 9/11, essentially one decade removed from Desert Storm, we had divested from 134 fighter squadrons down to 88. For a lot of obvious reasons, 9/11 was a huge inflection point for the entire nation and our military. Throughout the week immediately following 9/11, we understandably executed a week of crisis, action, global force management sourcing.

While that pace of force element sourcing was expected from 12 to 19 September 2001, we probably couldn’t predict at the time that we’d follow that first week with another 1,000 weeks of crisis action global force management sourcing, where we deployed our force from across the globe at a rate that exceeded our ability to generate the force. Whether it’s money, muscle, tissue, morale, or combat power, if you expend it at a rate that exceeds your ability to generate it, that rarely ends well. We literally ate the muscle tissue of the Air Force in the form of reduced fighter capacity, reduced readiness, putting hard miles on older aircraft, driving more extensive sustainment efforts.

While the collective we, we the U.S., might have overlooked the impact to our conventional combat power, our peer adversaries definitely took note and they saw a once-in-a-century opportunity to increase confrontation and secure gains at minimal risk. With this increased competition in our two pacing theaters, it’s understandable that today, the INDOPACOM commander considers the PACAF-assigned fighter squadrons as essentially threshold forces required to execute his day-to-day combatant command theater campaign plans.

With Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine and threats to NATO, it’s understandable that the EUCOM commander also considers the USAFE-assigned units as threshold forces required to fulfill NATO commitments and execute his combatant command theater campaign plans. This increased peer competition requiring combatant command exclusive utilization of their assigned fighter squadrons has left a smaller U.S.-based fighter force to fulfill rotational requirements to CENTCOM, to respond to crisis, execute homeland defense, and POTUS support.

A little bit about that peer competition. Whether it’s international airspace, high seas, outer space, the Arctic or cyber space, the majority of peer competition occurs in the global commons. While sometimes aggressive, most of this competition is professional as nations convey their national perspective and their intentions.

The most intense area of competition is when and where a nation seeks to migrate a common area into a new national sovereign. There’s a lot of reasons for this. Access to resources, area of influence, and the fact that once they subsume a common area into their sovereign space, it is significantly harder to compete against the nation in that new sovereign space.

Competition in the global commons often precedes competition of the highly contested sovereigns. It’s important to delineate between forces that compete in the global commons and forces that can actually compete in the highly contested sovereigns. It is that stark increase in pure competition in the sovereigns, it should garner undivided attention because competition in the sovereigns runs the risk to escalate into conflict in the sovereigns.

This is why you need a high-capacity, highly cable air force to keep adversaries out of your sovereigns and to retain the capability to punch into their sovereign space. That’s why we designed to build SR-71s, RQ-170s, F-117s and B-2s, to operate over sovereign territory, built cyber capabilities to punch into sovereign networks, advanced fighters to establish air superiority across contested airspace.

If you’re going to be a resolute world power, you have to compete not just in the global commons but also in the highly contested sovereigns because if you can’t compete in the highly contested sovereigns, you can’t fight in the highly contested sovereigns.And you have to recognize the correlation of capacity, readiness, competition, and risk.

Since we’re at AFA, and since I only have 40 minutes with you, we’ll limit the timeline discussion to 32 years and limit the force element discussion to Air Force fighters, a rather narrow scope of time and combat power, but the relationship of conventional capacity, readiness, competition, and risk could be discussed over a timeline of centuries across numerous capabilities for any service across any war fighting domain.

As discussed, we’ve become smaller over the past 31 years. There is little risk to becoming smaller if there’s a commensurate decrease in deployment taskings and global security risks. The exacerbating challenge of getting smaller over the past 31 years is also getting older in terms of airframe life. The slide’s a little counterintuitive, as newer is up top and older is towards the bottom of the graph. There’s a lot that goes into readiness equation and one of them is airframe life. As airframe life directly drives your overall sustainment capability by aircraft downtime for maintenance, down for supply, down for depo repair, and down for modernization.

One of the other readiness levers is aviator flight hours and exercises. This decrease in flying hours added to the decrease in our fighter capacity, an increase in aircraft age, represents a significant impact to our nation’s conventional deterrence.

Accordingly, we should not remotely be surprised at how our strategic adversaries have responded to decrease in conventional deterrence. Nature abhors a vacuum, and unfortunately so do geopolitics. While I’m not going to beam off in a Newton’s third law of every action, there is corresponding opposite reaction, there is an unambiguous contrast of conventional deterrence and over peer competition.

A quick visit to our peer competitors would likely have detailed information on the third Taiwan Straits crisis in 1996, as well as the Mischief Reef incident. Then, PRC introduces the Su-27 into their air force. Four years later in 2000, they add the Su-30 to their arsenal. In 2001, a Chinese J-8 collides midair with a U.S. Navy EP-3 resulting the loss of the J-8 and emergency divert of the EP-3. U.S. Navy boat incident occurs in 2001, and in 2005 Chinese introduced the Chengdu J-10, their first production fourth-gen fighter.

Soon after, they field the PL-12 air-to-air missile to directly compete with U.S. fire power. More high seas confrontation with the U.S. Navy ship Impeccable incident in 2009. 2014 to ’16 saw the height of PRC island building in the South China Sea. Russia annexes Crimea in 2014. Also, in 2014, the Chinese introduced their advanced flanker, the J-16. In 2016, the PRC deploys surface-to-air missiles to the Paracel Islands. That same year, Su-35 enters service with the Chinese air force. In 2017, the J-20 China’s own fifth-gen fighter enters service.

Soon after, they introduced the PL-15, long range missile, which greatly challenges U.S. long range missiles. USS Decatur incident occurs in 2018. 2021 starts a spike of aircraft incursions in the Taiwan Air Defense Identification Zone. 2022, Russia invades Ukraine on 24 February, exactly 31 years to the day of the Desert Storm ground invasion. Last month, PLA live-fire drills are executing in response to Speaker Pelosi’s CODEL visit.

At this juncture, some folks may surmise that I’m trying to make a case for 134 fighter squadrons of 10-year-old aircraft, where pilots get over 20 hours a month. While that wouldn’t outright be wrong, it would completely miss the point. The point is, in 1990 what nation state would want to challenge that level of conventional combat power? What nation state wants to pick a fight with an Air Force of 134 highly cable fighter squadrons that are organized, trained, equipped, and honed to a fine edge to fight a peer adversary.

The answer is no nation in their right mind, and accordingly, when you have conventional overmatch, strategic risk is low. But that’s not where we’ve arrived in terms of conventional deterrence and that’s not where we’re headed with respect to peer confrontation.

By any measure, we have departed the era of conventional overmatch to arrive at growing strategic risk. We’ve seen an increase in peer confrontation from Russia, to drive the nations of Europe to increase their defense budgets, to rapidly change national policies, to assist Ukraine and for Finland and Sweden to apply to join NATO.

Similarly, the discussion for our nation, in our nation’s air force, is how. How after 30 years of increased peer confrontation do you best contribute to our nation’s conventional deterrents to better manage strategic risk? To solve any fighter force challenge, you must engage in work—the range, sensor, weapons, readiness, sustainment, enterprise, as well as capability and capacity. We don’t have time to discuss all those equities, and it’s challenging to discuss high-end sensors and weapons in an open forum, but that said, capacity also has to be carefully navigated also due to releaseability concerns.

Every service has classified readiness metrics provided by the undersecretary of defense for personnel and readiness. Combatant commands have operational plans that are also close hold. Our own internal TACAIR study was classified and global force management, once you tie specific units, specific locations and specific timelines, outstrips this venue.

However, the Air Force We Need study, the 386 operational squadrons directed by the 2018 NDAA was unclassified and correctly highlighted that the Air Force needs 62 fighter squadrons. So accurate and unclassified studies do exist for our discussion.

In basic terms, the fighter aviation arm of Air Force has to do four main tasks. We have to compete forward across the globe. We have to respond to crisis wherever it presents itself. We have to protect the homeland, including the president, and we have to be ready to fight, which requires a robust training regimen.

As we compete forward, we first have to compete per the National Defense Strategy in our pacing theaters. With China growing more confrontational every day, the INDOPACOM commander requires 13 fighter squadrons to execute his combatant command theater campaign plans. The EUCOM commander tasks six fighter squadrons, and it’ll grow to seven, to fulfill our NATO obligations and execute theater campaign plans, amidst Russian aggression in Europe.

As mentioned, we can’t dive into the specifics of global force management in terms of exact units, numbers, dates or locations, but we’ve had seven, eight, upwards of nine fighter squadrons in CENTCOM at any one time just in the past few years. As we don’t have any permanently assigned fighter squadrons in CENTCOM, those units are rotational through our four-bin Air Force Force Generation readiness construct.

For ease of explanation, if, and that’s an if, we only had two fighter squadrons in theater for CENTCOM commander tasks across each of the four bins of AFFORGEN, that would require eight fighter squadrons for CENTCOM, so 28 fighter squadrons is required to compete forward day-to-day across the globe.

To respond to crisis, we have immediate response force options for the secretary of defense. Again, I can’t say exactly how many fighter squadrons we provide for crisis response options, but it’s called SECDEF options plural, not SECDEF options singular. We’ll just say two fighter squadrons across the four bins of AFFORGEN requires us to have a minimum of eight fighter squadrons dedicated to respond to crisis.

Those eight immediate response force fighter squadrons added to the 28 compete forward fighter squadrons is 36 fighter squadrons, but before we compete forward and before we respond to crisis, we have some must-pay bills here at home. Homeland Defense is the National Defense Strategy’s number one priority. The Air Force has protected our nation skies for decades from a high of 5,800 fighters on alert in 1958 to a low of four armed fighters on 9/11.

In 2010, the Air Force operated 18 alert locations across the continental United States, Alaska, and Hawaii. Our homeland defense lay down has not changed dramatically since then and the specifics are not releasable, but for day-to-day capacity requirements, while these alert sites do not need an entire fighter squadron to execute their homeland defense operations, the Air Force needs eight fighter squadron equivalents to ensure the skies of our nation remain safe.

Those eight fighter squadrons combined with the previous 36 that are required to compete forward and respond to crisis brings us to 44 fighter squadrons. Related but completely separate from Homeland Defense is support to the president. Everyone knows that there’s top cover for key presidential events—State of the Union, Summit of the Americas, United Nations General Assembly, Camp David, et cetera. While this is related, it is not the same as Homeland Defense and is a completely separate force element that provides POTUS support.

Our Air National Guard and our Air Force Reserve fighter squadrons are mobilized to execute most of our POTUS support requirements across a 24-month cycle. When they’re done with that unique no-fail mission, they often go straight back to Homeland Defense at their home station. The eight fighter squadrons that rotate in and out of POTUS support added to our compete forward force, our respond to crisis force, our homeland defense force, totals 52 fighter squadrons.

Whether it’s new F-35s in the Lakenheath or Vermont, Madison, Alabama, et cetera, or as new units receive the F-15EX, we always have units in conversion and modernization. If there is an insufficient number of units in conversion, that means your fighter force is either getting smaller, getting older, becoming less capable, or all three.

When these units are training new maintainers or aviators or resetting sustainment infrastructure, they are not available to deploy unless there’s a national emergency. Those eight fighter squadrons combined with our compete forward force, respond to crisis units, homeland defense, and POTUS support total 60 fighter squadrons. So 60 multi-role fighter squadrons is the simple, unclassified math required for day-to-day ops, not combat.

A few things as we navigate this challenge and chart a way ahead in an increasingly dangerous world. We don’t have 60 multi-role fighter squadrons. We have 48 fighter squadrons and we have nine A-10 attack squadrons. The beauty of the A-10 and it’s a beauty, is that there are sons and daughters of our nation over the past 20 years of counterinsurgency ops are alive today because the A-10 showed up to an intense troops in contact close air support fight, so the Hog has rightfully earned its spot in the Combat Aviation Hall of Fame.

But today, permissive airspace is drying up. All of our pacing theater campaign plans, Homeland Defense, POTUS support, Baltic air policing, much less a high end fight, requires multi-role fighters. With 48 fighter squadrons working to execute the requirement of 60 fighter squadrons and with the must pay bills of Homeland Defense and POTUS support, we take a hit in our compete forward effort, a hit in readiness, a hit in modernization, and a hit in our respond to crisis requirements where the crisis that they’re responding to is often a crisis of insufficient fighter capacity.

This is an acute issue for our Air Force and we are not the first nation to face this challenge, nor are we the only air force currently facing requirement-to-resource disconnect. The Germans face this challenge in 1942 and they developed some incredible weapon systems in their strategy to win World War II. This effort realized a generational leap in capability. The first rocket-powered fighter, ballistic missile technology, unmanned aerial vehicles, the first fighter jet and the first operational jet bomber, which, by the way, was the last German aircraft of the war to fly over the U.K. in April 1945.

These capability advances are truly remarkable, but the fatal flaw on the German strategy is that they accomplished these incredible capability advances at the expense of both their fighter capacity and their combat readiness and were completely destroyed by overwhelming Allied capacity.

Our nation, our Air Force are at their finest when we’re faced with a big challenge. We have one now and that’s to field a combat credible conventional deterrence in the face of overt peer confrontation. The requirement for 60 multi-role fighter squadrons for day-to-day ops around the globe is not going away anytime soon.

That’s one of the reasons that the Air Force We Need study accurately determine that we need 60-plus fighter squadrons. That’s also the reason that former Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson’s Senate testimony that, “The Air Force is too small for what the nation’s asking it to do,” is still factual. In terms of the how, first, follow the fighter roadmap, with a minimum of 72 new fighters a year to a highly capable, high capacity, multi-role fighter force.

Second, when you’re working this topic—range sensors, weapons readiness, capability, sustainment capacity, all of it matters. The strength of your fighter force is only as strong is your weakest attribute. Third, when you’re operating in a tough neighborhood, travel with friends who know how to fight. We have to leverage key security pacts like AUKUS, key alliances like NATO and key partner agreements to keep a coalition fighter capacity and capability advantage.

I didn’t have time to talk about it today, but we have to accelerate the combat collaborative aircraft research and development as well as the requisite autonomy authority and resilient comms that they’re going to need to address our fighter capability and capacity challenges.

Finally, we must realize that our multi-role capacity fighters that execute our capacity missions, they free up our high-capability fighters, our long range killers, that are need to execute peer competition and close our long-range kill chains. With that, thanks again to AFA and for your time. I’m happy to take any questions at all. Thanks.

Maj. Gen. Doug Raaberg

You got a packed audience, so why don’t I just take the questions for you.

Gen. Mark D. Kelly

OK.

Maj. Gen. Doug Raaberg

This is not rehearsed by the way. What we’d like to do is pick up from last year’s presentation, which Gen. Kelly just addressed, and that’s the fighter force. And we still had some folks in the audience back then that I’ve kept the questions. I’d like to touch on a few of those, sir. The first one is, since the 60 fighter squadron replacement that you laid out just now, it is day-to-day ops, what is the quote capacity solution for a major theater war?

Gen. Mark D. Kelly

Well, major theater war is aptly named because it’s going to consume a majority of anything and everything you thought you had enough of—your fuel, your weapons, your aircraft, your equipment, your Airmen, your money, your time, your focus and resourcing in major theater war from a force that is considered healthy is still going to drive challenges and it’s going to require some pretty quick discussion, some prioritization, and decisions.

Rapidly, it’ll be evident that, well, the chess pieces you have are the chess pieces you have. In terms of the fighter force, as I described, as 48 fighter squadrons and nine attack squadrons. We’re going to put them exactly where we’re told to put them, but it goes a little bit to former Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld, I think it was 2003 or 2004 when he stated, “You go to war with the military you have, not the military you want or wish you had.”

As we resource a major theater war from a capacity limited force, by definition it’ll require utilizing units that were originally intended for some other task and purpose. First one that comes to mind because it’s often the first one that comes to mind to our great friends and the joint staff is utilizing units that were intended for another theater.

Today, as we sit here, our F-22s are deployed from our pacing theater at Elmendorf over to EUCOM to help buy down the risk brought on by Russian aggression. Second way is to utilize units that were intended for another timeframe. When theater risk spikes, the theater forces engage that, we augment it with units that are earmarked for this time period, our commit bin, but if the risk still outstrips that, there’s going to be people that peek over the fence and look at the other bins of our AFFORGEN model, ones that are earmarked for six months and a year down the road who do not have the requisite rest or the requisite readiness. And if we choose to use them, we could do that, but we would continue decades of overconsumption of the Air Force.

Similarly to that, the third way would be to utilize unit that are intended for another rung of your escalation ladder. We don’t normally mobilize, activate our garden reserve at the first spike of risk, but you could, but you wouldn’t have that option in reserve for your forces in reserve.

The fourth option would be to utilize units intended for frankly a completely different mission within your peer fight requires. You could send in your 9, 8, 10 attack squadrons, and Hog pilots are incredibly courageous, brave, skilled warriors. They’re going to go and their performance would make our nation proud. Guarantee it.

But I would offer that while every human endeavor in a shooting war requires some semblance of individual courage, skill, and the acceptance of individual risk, if the gap between your theory of victory and your force construct needs to be bridged by extreme skill, extreme courage and the acceptance of extreme personal risk, that’s probably, in my opinion, a key indicator you need to look at your theory of victory or your force construct.

Probably, the last one, at least the last one I could think of is, and because it’s often the last option chosen by militaries that are on their final leg, is to utilize units intended for your institution, i.e. your institutional force. For the fighter force, that means you could commit all, part, or some of your formal training unit, operational test, aggressors, weapons school, et cetera. If you use part of the supply chain in there, it’s probably not going to break glass, but if you’re leaning heavily, heavily on this course of action, my opinion is, and history would tell you, a thousand years of history would tell you, that you’ve probably migrated past the juncture where you’re trying to win and you’ve essentially, I’d say, pulled the goalie and you’re trying really hard not to lose.

These are decisions we would make and we’d expect to make in major theater war. One of the themes of the brief that hopefully came out is we are just challenged by having to make those decisions day in, day out, in our day-to-day fight. Thanks.

Maj. Gen. Doug Raaberg

Sir, let’s take a second question here. That since you referenced to Germany’s capability development, absent a parallel capacity surge on their part is an example from 80 years ago, let’s bring it to today, do you believe that it translates well to today’s challenges?

Gen. Mark D. Kelly

Well, short answer is absolutely, yes. I believe it translates. It frankly doesn’t matter if it was 80 years ago or 80 days ago. A nation’s strategy almost always, almost hinges on three rather timeless foundational criteria that most folks that’ve been doing this for three decades are aware of. That’s first of all, national will, commitment, sense of urgency. Number two is a nation’s ability to identify and develop true war winning capability. Three is the nation’s ability to produce those capabilities at scale and sufficient capacity.

As far as the question goes, Germany, one, they were facing an existential threat. There’s some natural motivation, sense of urgency and commitment. Number two, their research development, science technology, engineering enterprise was world class. Matter of fact, it was the world standard in almost every line of effort, shy of nuclear physics. It’s proven out by what they developed under fire.

Their Achilles heel was essentially what the RAF and the Eighth Air Force bombed day and night, which was their production capacity. They couldn’t produce that scale, at least not any scale that would appreciably changed the difference. If folks don’t have my affinity, they’re more aligned to my wife, the lack of affinity for history, they want a more contemporary example, there’s a reason why Secretary Kendall, Chief Brown and others often reference China.

Three of those reasons are one, very well-articulated, unambiguous national commitment and their worldview of their autocracy at the top of it. Number two, their research development, science technology and engineering enterprise, well-developed to identify and develop true war winning capability. Three, they’re resourcing strategy to produce those capabilities at scale. That doesn’t mean they’ve had an easy or short path. They’ve been working at this for decades, decades and they’ll get together, I think it’s next month, mid-next month, to do their 20th National Party Congress.

It’s mostly a political get-together, but they’ll be breakout sessions if not official, unofficial. They’ll assess essentially that slide, their ability to produce the airspace, cyber, and naval force to fight the U.S., as they’ve done in every National Party congress, which they do every five years. Those discussions generate, I’m sure we’re not invited, significant amount of discussion, debate, decisions. Their decisions in the past that have seen them cut their ground force in half to resource the airspace, cyber, naval force they need to fight the U.S.

I think it’s 300,000 they’ve cut just in the last five or six years, I think, so don’t quote me on that and definitely don’t misquote me and say Kelly recommends the U.S. to do the same thing. The fact of matter is, the Chinese example and the German example are simply statements of fact, and we’ve been running parallel processes in our nation, the exact same timelines. As a matter of fact, 80 years ago when the German Reichstag was directing the Luftwaffe to develop game-changing capability, the War Department was directing the U.S. Army Air Force to produce more winning capacity to the tune of roughly 2.3, 2.4 million Airmen, just shy of 80,000 aircraft.

As that process runs its course in our nation today, and it does, if we’re told to accelerate the development of NGAD, our sixth-gen air dominance fighter and produce it at significant scale, that’s how we’ll execute and we’ll defeat any force on the planet. If that process runs its course and we’re told to commit billions of dollars to refurbish 35- and 45-year-old airplanes, that’s how we’ll execute. I apologize, the short answer to your question is yeah, I do believe that any industrial nation’s journey through this force buildup and strategy is applicable to help inform our journey.

Maj. Gen. Doug Raaberg

Sir, final question. Obviously the Space Force and the Air Force is observing and oriented on the current events that you just laid out in your presentation. What do you think the lessons will be for the fighter force coming out of the Ukraine conflict?

Gen. Mark D. Kelly

OK. I believe, this is a personal opinion, I believe that institutions and individuals will largely, I’d say focus, highlight, and learn what they want to learn out of the Ukraine conflict. I think our great Army partners will highlight that you shouldn’t take an undisciplined, untrained, unprofessional, unprotected, unresourced, undisciplined armor column and race it to another nation’s capital.

I believe our shipmates in the Navy, finest Sailors on the planet, will highlight fleet defense and sea control. I believe our brother and sister Guardians will highlight the incredible contributions of our unblinking ISR constellation, our communication infrastructure, our precision navigation and timing infrastructure in LEO and elsewhere. I think all those observations will be accurate.

I think folks that are in the know, and that’s the key word is in the know, of what our cyber and our intel Airmen have done in this conflict for the defense of Europe, support of NATO and frankly the bastion of defense of freedom and democracy in Ukraine will know that this conflict was their finest hour by every sense of the word.

To your question, fighter force, I frankly think it’s more of a question for the nation that we should have. We should elevate it out of fighter force, out of bomber force, out of ISR force and ask ourselves, as contributors to the national discussion is if a nation wants an air force that can establish air superiority at the time and place of its choosing, execute air defense takedown at the time and place of its choosing, execute persistent global decision attack at the exact same time and place of our choosing, set the conditions for a low-casualty, 100-hour ground campaign comparable to Desert Storm, well then you need the first-class Air Force.

If on the other hand, that’s considered too fiscally challenging or you’re constrained by legacy budgetary rules and makes it unobtainable and you’re OK, and, it’s not an or, and you’re OK with months, more like years, of bloody trench warfare and a grinding artillery duel with thousands of casualties on the scale of Ukraine or World War I, you don’t need a first rate Air force. A second rate Air Force will handle that just fine.

But as we visit all of our great Airmen here at AFA and I get the privilege of going over with Gen. Finerty to visit the great elected leaders we have on the Hill, and they work hard, their staffers work hard, they commit a whole lot of their life and energy away from home here. We, by definition, whether you’ve been wearing the cloth of the nation for 36 months or 36 years, you owe them by law you best military advice.

When this topic comes up of a first rate Air Force or a second rate Air Force, I would offer that one—or they’d be voters and taxpayers—one, choose wisely. Two, choose knowing that China’s building a first rate Air Force. Three, finally, I’d say choose knowing what we knew before 24 February, and that is when it comes to a nation’s blood, treasure, stature on the globe, the only thing more expensive than a first rate Air Force is a second rate Air Force. Thanks for your time. Appreciate you being here.

Maj. Gen. Doug Raaberg

After a combat sortie, there’s only three words you want to hear in the debrief, you crushed it. Let’s give Gen. Kelly a big hand. Thanks very much.