The U.S. and its allies intercepted American B-1 bombers coming across the Atlantic toward North America, in a NORAD-led exercise simulating an enemy attack on June 26.

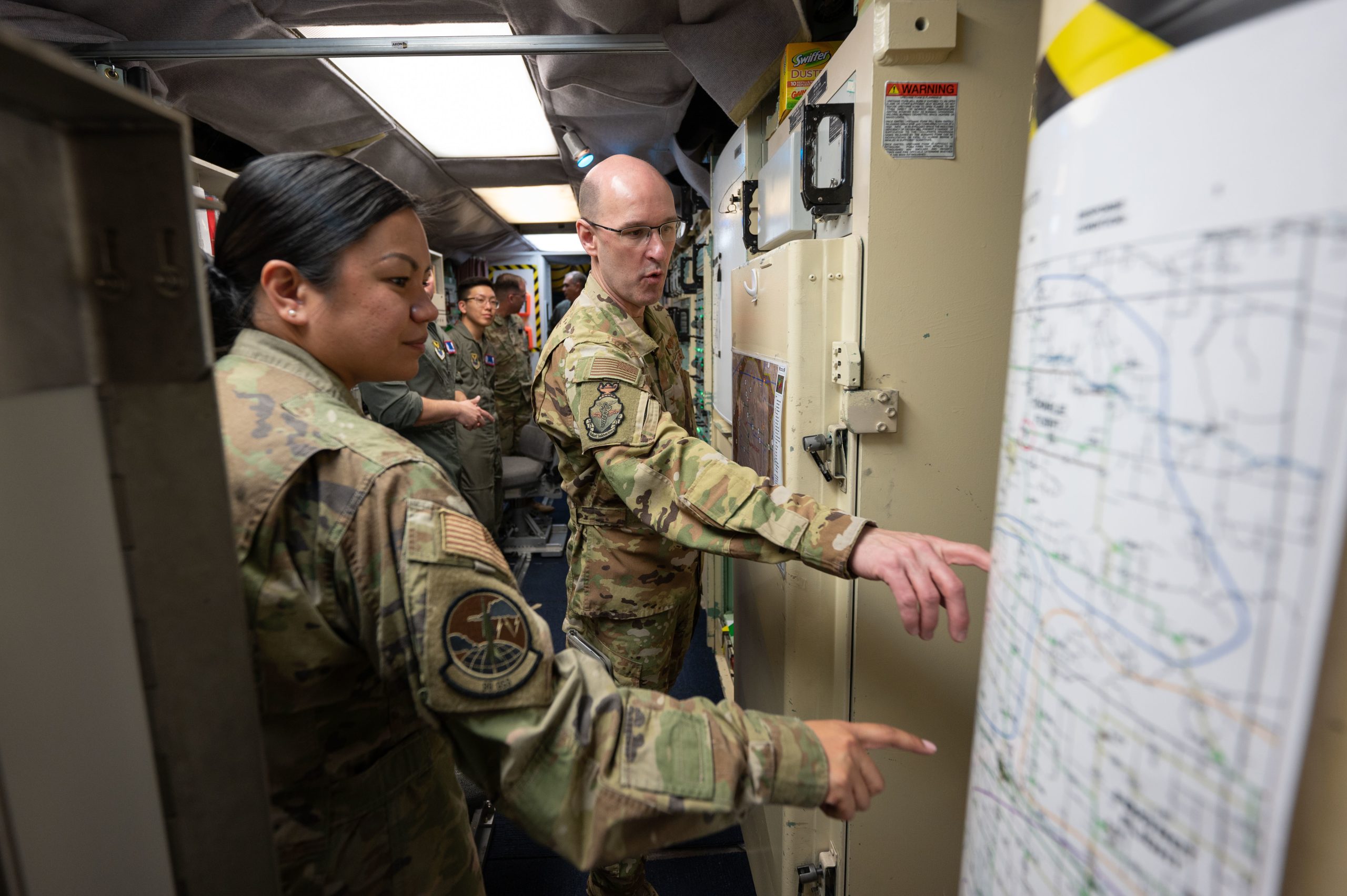

During an exercise dubbed Noble Defender, B-1 Lancers that were leaving Europe after a month-long Bomber Task Force deployment were successively tracked and intercepted by the U.S., Canadian, British, Danish, Finnish, Norwegian, and Swedish militaries.

A NORAD official told Air & Space Forces Magazine two B-1s were met in the skies by four U.K. fighters—two F-35s and two Eurofighter Typhoons. Denmark sent two F-16s, Sweden sent two JAS-39 Gripens, Norway sent two F-35s, and Finland sent two F-18s.

“All nations sequentially intercepted … B-1 Lancers in the North Atlantic region and off the east coast of Canada as it transited from Europe to North America on June 26,” NORAD said in a statement posted on Twitter.

Protecting from the simulated threat to the U.S. and Canada were two U.S. F-15C Eagles from Barnes Air National Guard Base, Mass., two Royal Canadian Air Force CF-18 fighters—a variant of the American F/A-18 Hornet—and a U.S. KC-135 Stratotanker, the NORAD official added. NORAD, short for North American Aerospace Defense Command, is a joint U.S.-Canadian effort.

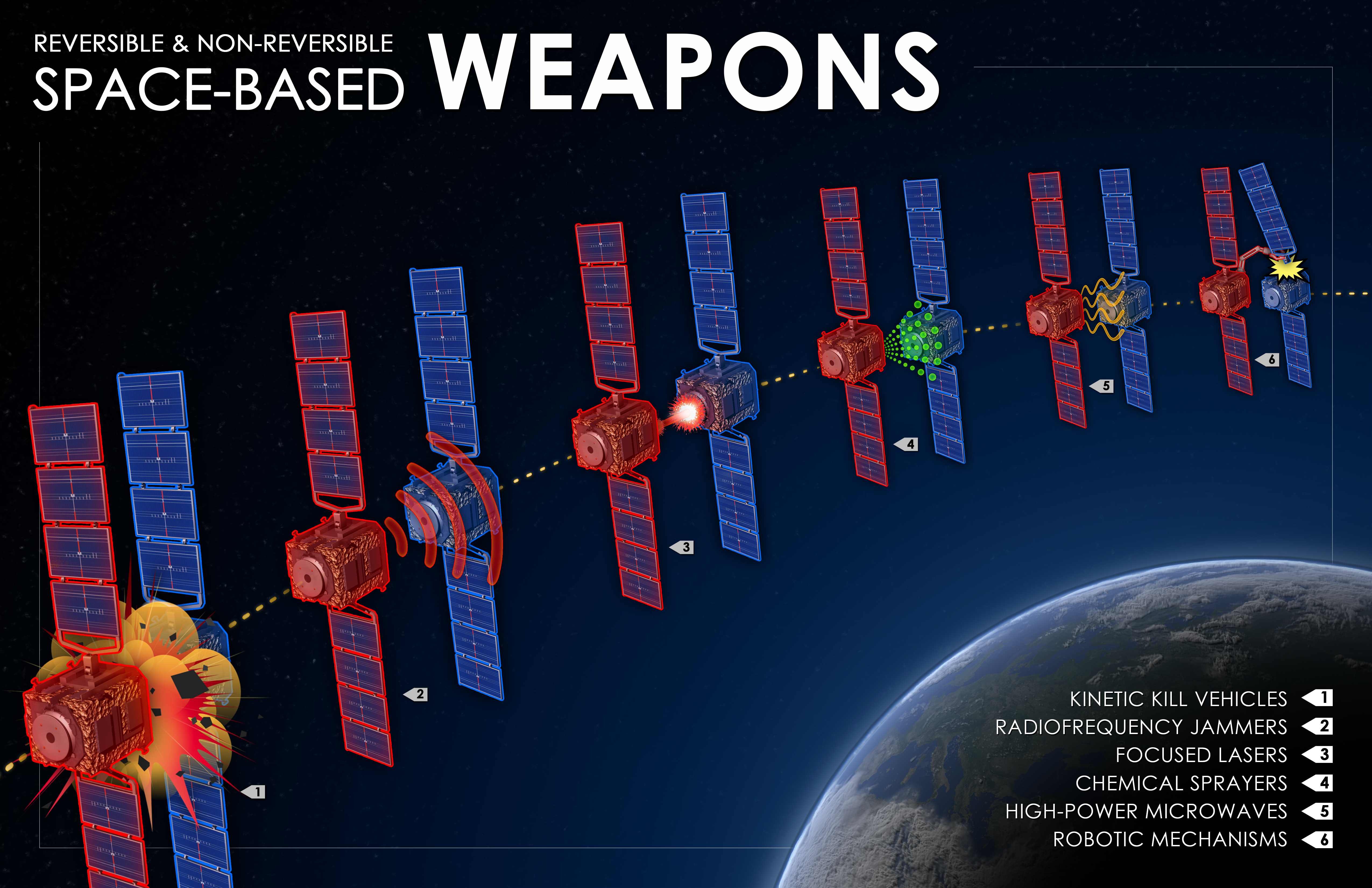

“NORAD units executed maneuvers designed to defend the eastern approach of North America from simulated cruise missile threats in this particular operation,” according to the 104th Fighter Wing at Barnes.

The NORAD official noted that the command holds regular iterations of Noble Defender, which vary depending on the specific exercise, to keep its forces ready

“These intercepts demonstrated a cooperative and collaborative layered defense to strengthen our ability to deter potential threats,” NORAD added in its statement.

The intercepts made a full-circle deployment for the B-1s assigned to the 7th Bomb Wing at Dyess Air Force Base, Texas. The “Bones” were immediately met by a Russian Su-27 fighter when they entered European airspace in late May. A total of four B-1s completed the BTF, which involved the first landing of U.S. bombers in Sweden since World War II, as the U.S. looks to signal its growing alliance with the prospective NATO member.

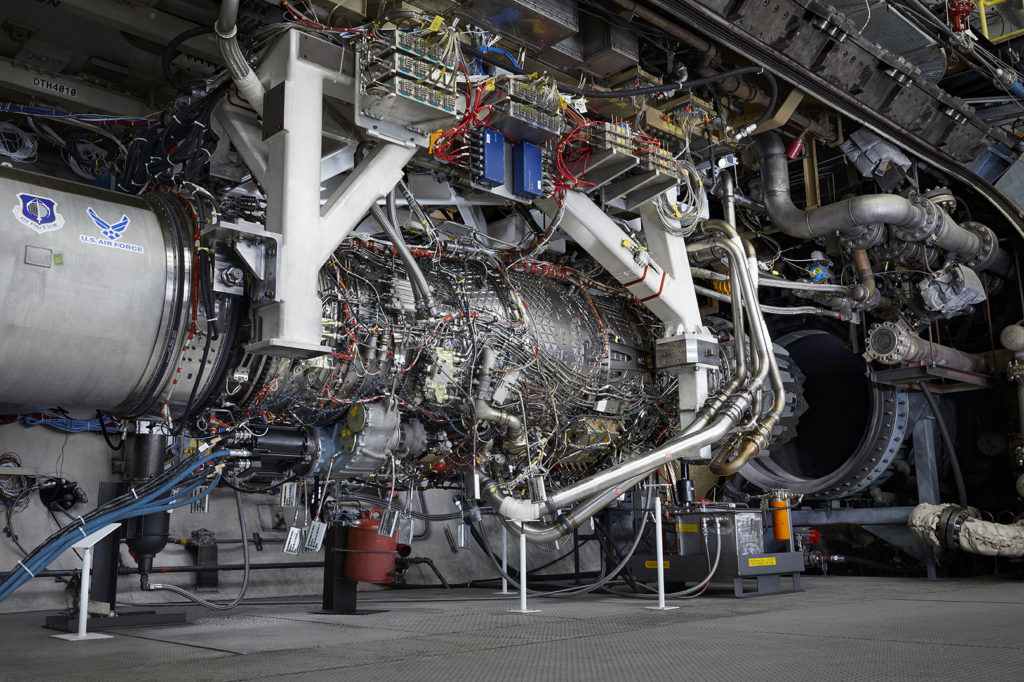

U.S. Air Forces in Europe said in a press release that the highlights of the deployment included “the historic landing in Sweden and the first-ever hot-pit refueling in Romania.”

“The landing in Sweden fortified not only the friendship between the U.S. and Sweden, but the collective defense of Europe,” the USAFE release added.

The aircraft also flew over the Baltics and Balkans, participated in an Arctic defense exercise, flew all the way to the Middle East and back in a live-fire launch of a JASSM long-range cruise missile and JDAM guided bombs over Jordan and Saudi Arabia, and participated in the Paris Air Show.

“Throughout their rotation, the B-1B Lancers have built critical relationships throughout the Arctic, Central, and Eastern European regions, which has enhanced the coalition’s ability to respond to incursions threatening freedom of maneuver and navigation,” USAFE said.