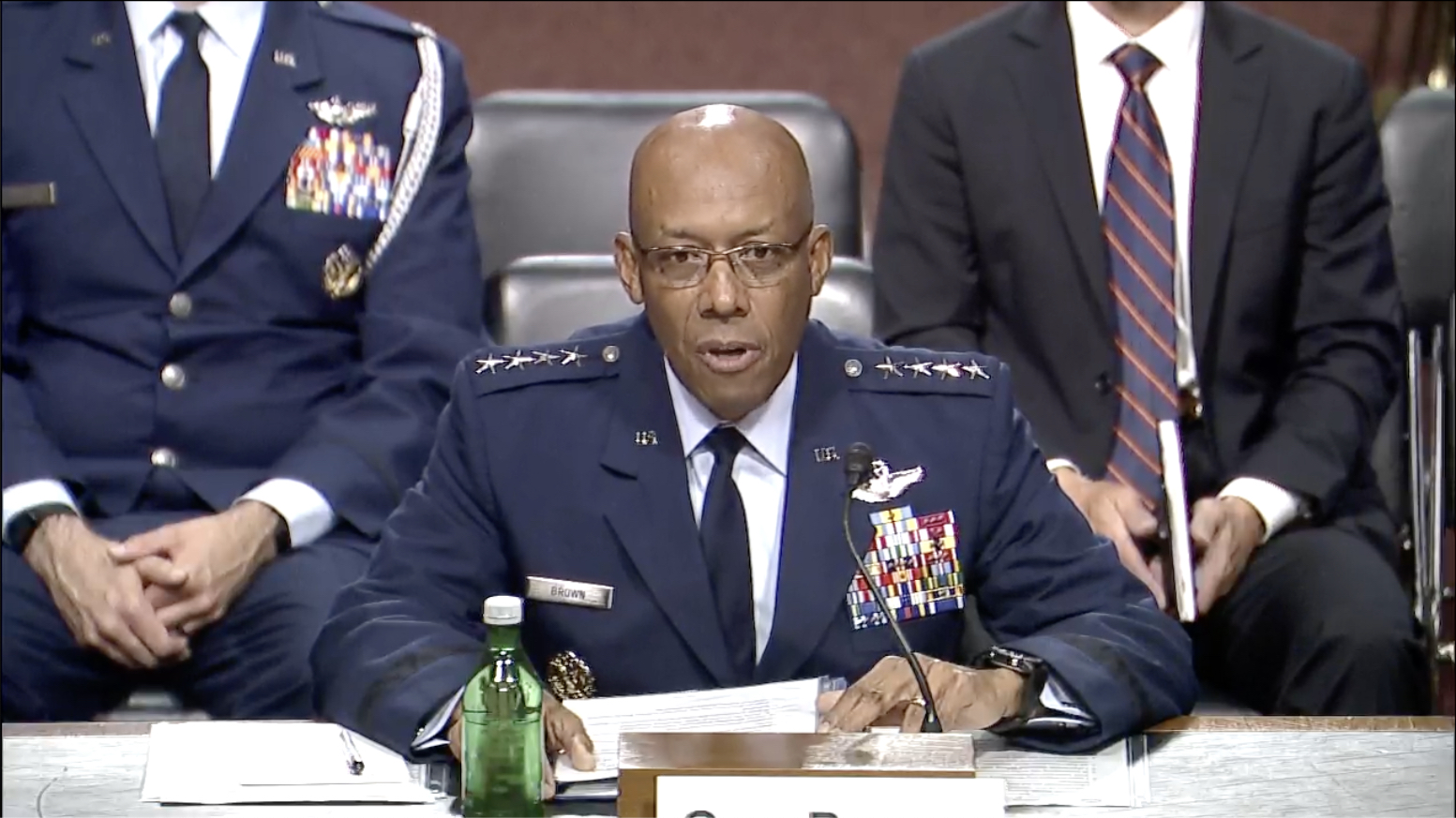

The Air Force is trying to work with Congress to shift funds around after the service was forced to pause bonus programs and permanent change-of-station (PCS) orders due to a budgetary shortfall, Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr. confirmed July 11.

But lawmakers have yet to approve the request, and it is unclear if and when that approval might come.

On July 10, the Air Force announced that in order “to avoid exhausting funds” in its military personnel account, the service would not award any new pause selective reenlistment bonuses, aviation bonuses, and assignment incentive pay. All pending PCS orders with a departure date past July are also being reviewed, potentially delaying moves for some Airmen. An Air Force official told Air & Space Forces Magazine the budget shortfall was due to higher-than-expected PCS costs due to inflation and other additional retention and recruiting bonuses this year.

Normally, the Air Force could go to Congress and get authorization to shift money around if there is a shortfall in one area, such as personnel, Brown said during his confirmation hearing to become Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

“Part of this is for us to be able to work with Congress to get the reprogramming in place,” Brown said, noting that the Air Force hopes it “can reverse and minimize the impact to Airmen and their families throughout this fill the rest of this fiscal year.”

A service official told Air & Space Forces Magazine the request for reprogramming is still pending before Congress. The reason why is under dispute.

Sen. John Hickenlooper (D-Colo.) released a statement July 11 saying the “House Armed Services Committee has placed a hold on the reprogramming of funds for all Military Departments. While DOD has requested approval for several requests, the Air Force is first impacted due to a budget shortfall.”

Hickenlooper’s statement and multiple media reports indicated the hold on reprogramming is tied to the basing decision for U.S. Space Command, which is under review by Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall after years of disputes and controversy.

In a statement to Air & Space Forces Magazine, HASC chairman Rep. Mike Rogers (R-Ala.) claimed Hickenlooper is making a “partisan, parochial, and untrue misrepresentation of HASC processes. The Committee is continuing to review reprogramming requests from the Department of Defense.”

Back in early 2021, Huntsville, Ala., was selected as the permanent location for SPACECOM, moving the combatant command away from its temporary home of Peterson Space Force Base, Colo. Alabama lawmakers, including Rogers, have signaled they might use the power of the purse as a bargaining chip to prevent the Department of Defense reversing the decision to move the command to Alabama.

“Chairman Mike Rogers’ decision to block the Department of Defense from routinely reallocating funds is dangerous and harmful,” Hickenlooper said in a statement. “This is not how our nation should make basing decisions. Period. It is, however, how you penalize our troops for the sake of narrow political interests.”

Regardless, as long as the reprogramming request is not approved, the Air Force is reviewing pending PCS orders for Airmen whose projected departure dates are Aug. 1 or later and approving some on a “priority basis,” but others will be delayed. Those who have already received orders will be allowed to move. Airmen who have already signed a contract or been approved for certain bonuses will continue to receive them, but the Air Force is no longer accepting new Airmen into affected bonus programs.