The U.S. military relies on allies to conduct operations around the globe. Now, the U.S. is pushing for greater cooperation with its partners in Earth orbit.

The head of U.S. Space Command, Army Gen. James Dickinson, took a weeklong trip to Europe June 21-27 to meet with U.S. allies, some of which are starting up their own space commands, SPACECOM said in a July 5 news release.

Dickinson visited U.S. troops at Pituffik Space Base (formerly known as Thule Air Base) in Greenland, before heading to the French aerospace hub of Toulouse.

U.S. military space officials have been making a concerted effort to enhance America’s cooperation with European allies. Russia’s war in Ukraine has highlighted the critical importance space plays in intelligence, command and control, communications, and guided munitions.

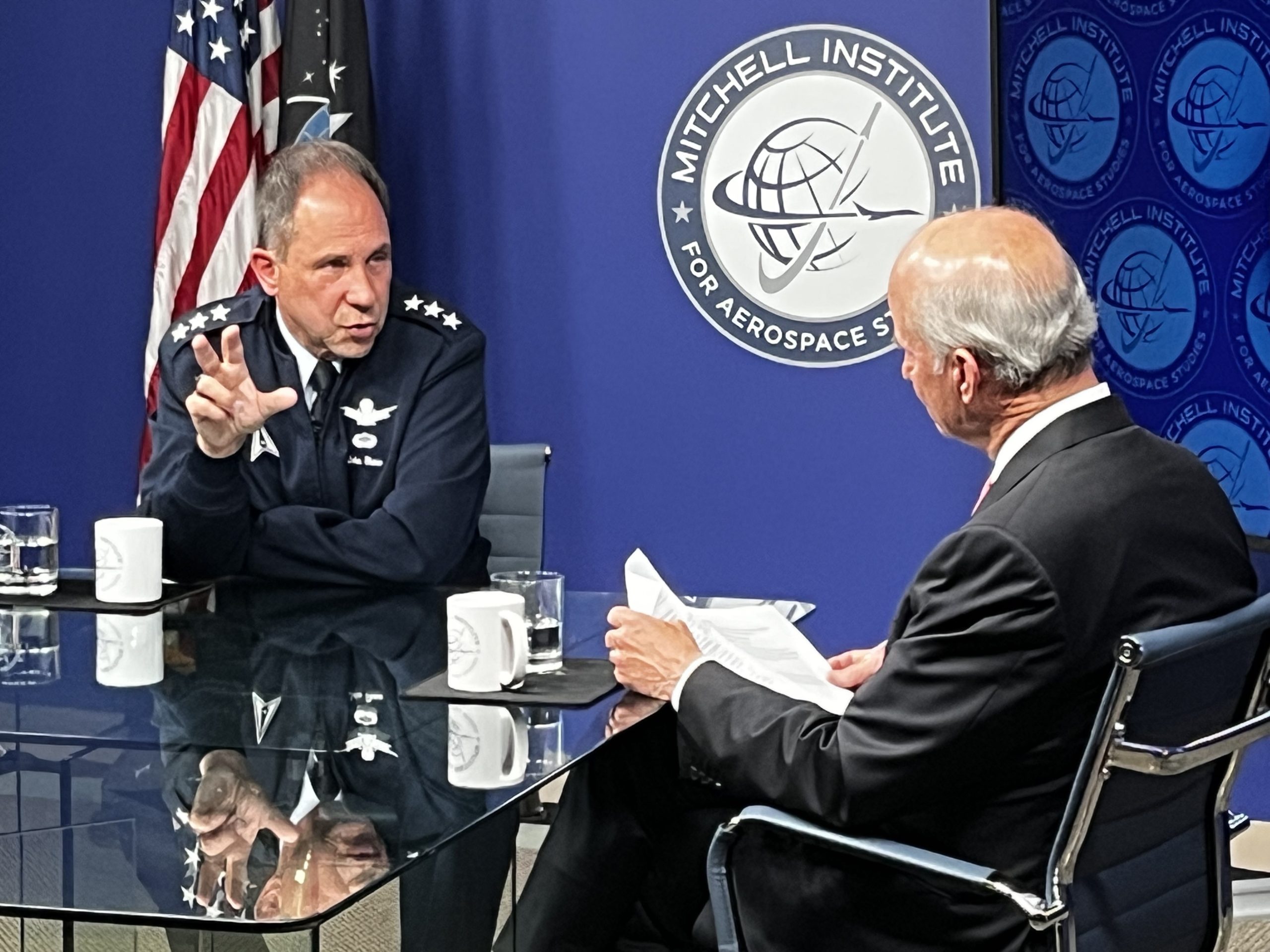

In May, U.S. Space Force Lt. Gen. DeAnna Burt, deputy chief of staff for operations, cyber, and nuclear—the service’s Chief Operations Officer—visited NATO headquarters in Brussels in a bid to reinforce U.S. support for the alliance’s burgeoning commitment to space as a military domain. Dickinson also made a pitch to NATO, sharing a “vision for the future of collaboration in space,” according to the command.

Dickinson “focused on the importance of space to the global way of life; the threats facing the domain; the criticality of continued cooperation in ensuring the safety, security, stability, and sustainability of the domain,” SPACECOM said.

Dickinson spoke to NATO’s Military Committee and visited NATO’s Space Center of Excellence, a body established as the “catalyst” of the alliance’s role in space.

NATO declared space was the “fifth domain” in 2019—the year the U.S. Space Command and Space Force were created. In 2021, NATO said “attacks to, from, or within space” could invoke the alliance’s Article Five mutual defense clause.

Space Force will create its component inside U.S. European Command to transfer its existing space operations, part of U.S. Air Forces in Europe, into a component separate from the Air Force.

Dickinson also met with British officials, following Burt’s trip to London a month and a half earlier. Britain, too, has a space command, and the U.S. and U.K signed an agreement last year to work together even more closely in space.

“From a security perspective, an increasing number of countries are looking to use space to enhance their military capabilities and national security,” the Secure World Foundation wrote in its 2023 Global Counterspace Capabilities report.

Dickinson’s visit reinforces America’s push for the U.S. military and its European allies to marshal their forces against common threats such as Russia, which conducted an anti-satellite (ASAT) test in 2021, a move which the U.S. has repeatedly pointed to as an example of a tangible threat to space operations. China has conducted an ASAT test, mostly recently in 2007, and is bolstering its space capabilities. The U.S. also blew up one of its own satellites in a test in 2008, but has since pledged not to conduct direct-ascent kinetic anti-satellite tests.

“The meetings held, and the information shared this week, will continue to lead to stronger partnerships and integration in the future, ensuring a safe, secure, and sustainable space environment for all,” Dickinson said in a statement following the visit. “The bond between Europe and North America has made the North Atlantic Treaty Organization the world’s strongest military alliance, and I’m proud to witness how the alliance is making progress in integration in space.”