The Pentagon plans to use U.S. Air Force C-17s and C-130s to deport 5,400 people currently detained by Customs and Border Protection, officials announced Jan. 22, the first act in President Donald Trump’s sweeping promise to crack down on immigrants in the country illegally and increase border security.

And that may not be the end of the Air Force’s role in implementing the new administration’s policy to more tightly control the border.

“Right now, we also anticipate that there could be some additional airborne intelligence surveillance support assets that would move down to the border to increase situational awareness,” a senior military official told reporters.

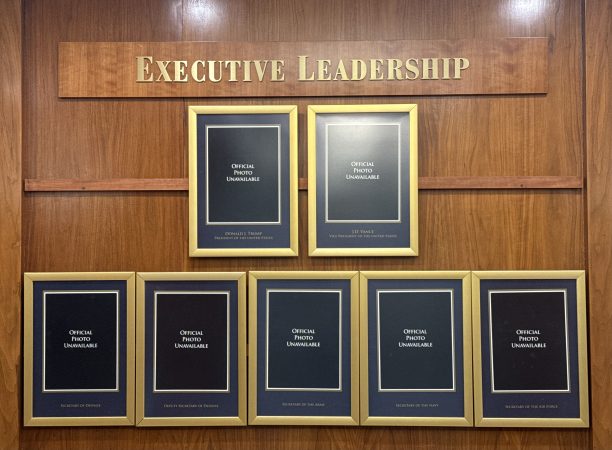

Acting Secretary of Defense Robert Salesses said in a statement that 1,500 Active-Duty troops are being sent to the southern border to take “complete operational control of the southern border of the United States.” Ultimately, as many as 10,000 could be deployed, the senior military official added.

“This is just the beginning,” Salesses’ statement noted.

The deportation flights will be carried out using two USAF C-17s and two C-130s, according to the Pentagon. Those aircraft, along with their aircrew and a handful of other personnel, will deploy to San Diego, Calif., and El Paso, Texas. C-17s from Travis Air Force Base, Calif. have already landed in El Paso and San Diego, people familiar with the matter told Air & Space Forces Magazine, a development confirmed by open source flight tracking data. Officials are still unclear where the thousands of people will be deported to, the Pentagon said.

“The State Department has the decision-making and has the relationships that they’re working with those countries that will ultimately be the source … to where these flights are going,” a senior defense official said.

The Pentagon said that the Department of Homeland Security would provide “inflight law enforcement,” not military personnel.

If additional airborne assets are deployed for surveillance along the border, they will be drawn from a variety of services and not just the Air Force, U.S. officials said. “This will be multi-service,” the senior military official said.

“Tactical UAS” could be used to “provide localized intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance in their particular area” and Army MQ-1 and Air Force MQ-9 drones could be deployed as well. Crewed surveillance aircraft are also an option under consideration.

“You have manned platforms that could fly in support as well—so that is still not fully decided yet,” the senior military official said.

The 1,500 troops that are being sent include 1,000 Soldiers and 500 Marines. They are joining some 2,500 service members already deployed to the southern border.

“These forces will work on the emplacement of physical barriers and other border missions,” the senior military official said of the new deployments. “First operations for them should commence within the next 24 to 48 hours. They’re moving right now as we sit here.”

UH-72 Lakota helicopters, in fact, have already started flying missions.

The operation will be led by U.S. Northern Command, which Trump charged to “seal the borders” by “repelling forms of invasion” in a Jan. 20 executive order.

U.S. troops are prohibited from performing law enforcement duties under the Posse Comitatus Act. But Trump said in his executive order that their use is justified because he has declared a border emergency to stop “forms of invasion including unlawful mass migration, narcotics trafficking, human smuggling and trafficking, and other criminal activities.”

Trump has directed that the heads of the Pentagon and Department of Homeland Security report back within 90 days on whether they think the 1807 Insurrection Act should be invoked, under which U.S. troops could be used to put down domestic violence.