Collins Aerospace has spent more than a half century developing electric power generation technologies that power aircraft around the world. Alongside its industry-leading engineering teams, Collins credits development of next-generation electric technology to its strategic partnerships. As technology continues to evolve in support of aircraft electrification, key relationships position Collins to help advance hybrid-electric propulsion technologies in support of sustainable aviation across both military and commercial sectors.

Advancing electric power systems for the military and beyond

Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL)

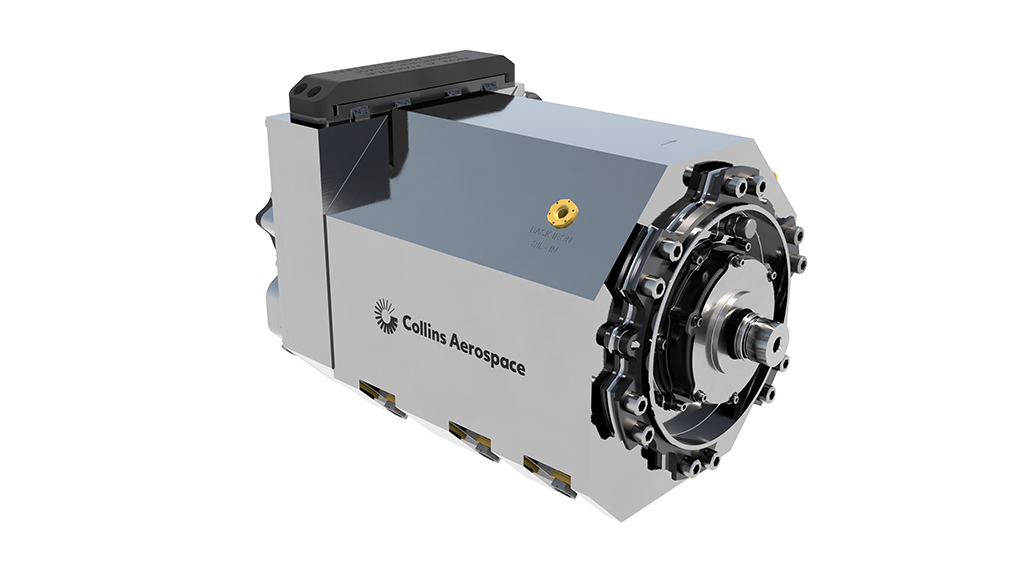

Collins is currently developing a 1-megawatt electric generator for the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) as part of its Advanced Turbine Technologies for Affordable Mission-Capability program. The low-spool generator could have multiple applications for future manned and unmanned military platforms.

“We have a long history of working with the Air Force Research Labs and they do a lot of the cutting-edge technology for equipment that ultimately ends up on aircraft,” said Todd Spierling, Principal Technical Fellow for Collins Aerospace.

With the addition of advanced mission systems, avionics and high-energy weapons, the next generation of military aircraft will require an order of magnitude increase in electricity that current aircraft require today.

“Next-generation military aircraft will require increased power and operational capabilities to perform their missions, and we’re extending the work we’re doing with electrification to more and more defense applications,” Spierling said. “So how do we do that? What does that equipment look like, and how do we supply that power to the airplane?”

Collins Aerospace has been working with AFRL for several years now on the design and manufacture of the 1MW generator, which could be used to power these systems safely and efficiently. Collins is now moving into the building stage – and this piece of hardware will be one of the first pieces to be tested in The Grid.

The Grid is Collins’ new next-generation electric power systems lab located in Rockford, Illinois. The lab will be used to develop high-power, high-efficiency motors, motor controllers, generators and distribution systems, in addition to providing a space for extensive electric system integration.

Partnering on UAV technology

In collaboration with Pratt & Whitney, Collins is advancing hybrid-electric propulsion technology through a number of demonstrator programs addressing a range of aircraft applications from advanced air mobility vehicles to single-aisle airliners. For example, the Scalable Turboelectric Powertrain Technology (STEP-Tech) demonstrator aims to advance technologies for distributed hybrid-electric propulsion systems for smaller aircraft such as high-speed eVTOL and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). The program completed its first engine run and integration test in early 2023. At the larger end of the scale, Pratt & Whitney and Collins are developing a hybrid-electric GTF engine demonstrator, as part of the SWITCH project, supported by the European Union’s Clean Aviation initiative.

As both Collins and Pratt & Whitney are businesses of RTX, the companies are uniquely placed to leverage collaboration between their closely integrated engineering teams, helping to accelerate the development of technologies for both commercial and military applications.

“When I think of aircraft electrification, what does it mean for the industry? What does it mean for our customers?” states Eric Cunningham, Vice President of Electric Power Systems at Collins Aerospace. “It means we’re going to start doing things differently and how we architect not just the systems, but the entire aircraft. If I think about what we did on the 787 and F-35 by going to a more electric architecture, Collins was the company that put those systems in place. And so, we’ve got a history of not just doing a component or two here and there, but we have the unique capability to integrate the entire electrical system including the generation, the control, the distribution, the emergency power.”

Military aircraft and the future fleet depend on the ability to execute unique mission profiles, pushing range, lethality and mission readiness. Demonstrator programs like STEP-Tech provide important opportunities for maturing technologies and exploring avenues to apply aircraft electrification to future applications, including military. The collaboration between Collins and Pratt & Whitney combines decades of expertise from each business’s specialties to execute advanced aviation systems utilizing electric architectures.

Cutting-edge advancements powered by partnership

With more than 100 years in military aviation innovation and advancements, Collins Aerospace understands the importance of partnership to truly transform the future of aerospace.

“We talk about this being the third era of aviation, when we went from piston engines to gas turbines and now to electrified propulsion. So, it’s a time to enter the industry when there there’s dramatic revolutionary things happening as opposed to periods of time when it’s more evolutionary,” muses Spierling. And these advancements couldn’t happen without the many partnerships that drive the future of electrified aviation.