The conflict in Ukraine is emerging as a critical test bed for new weapons technology, and while efforts to provide fighter aircraft to Ukraine remain stalled, those constraints do not seem to apply to advanced unmanned aerial systems (UAS).

The latest U.S. aid package for Ukraine, announced Feb. 24, includes an array of new UASs. Valued in total at about $2 billion, the aid comes out of the U.S. Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative (USAI), which funds purchases directly from industry rather than taking supplies from American stocks.

Caitlin Lee, senior fellow for UAV and autonomy studies at AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, said the UASs represent a natural evolution of new equipment for Ukraine.

“I think what you’re seeing is the U.S. building on the success of smaller drones in Ukraine and leveraging that as much as possible in the absence of the ability to send a larger aircraft, manned or unmanned, into the battle,” Lee said.

Neither Russia nor Ukraine have been able to achieve air superiority in the conflict, leading both sides to turn to drones to as a lower-risk means to attack ground targets from above. Russia has made extensive use of Iranian-made kamikaze drones to attack Ukrainian infrastructure, providing a novel and cost-effective solution to countering Ukrainian air defenses while still achieving air-to-ground hits.

Ukraine has also employed drones, including Turkish-made Bayraktar TB2s, and quadcopters for artillery spotting in the slugfest now taking place in the eastern part of the country. Ukraine has also used off-the-shelf drones to drop explosives, a tactic ISIS has used against U.S.-backed forces in Iraq and Syria.

The new UASs the U.S. will provide include systems either still in testing or that have only been used sparingly to date by U.S. forces. These include Switchblade 600s, Jump 20s, ALTIUS-600s, and CyberLux K8s. Only the Switchblade has been promised in past aid packages.

Pentagon Press Secretary Brig. Gen. Patrick S. Ryder said in a press briefing Feb. 24 that unmanned systems are now “part of the modern way of warfare.”

“I think it’s become apparent to everyone in the last five to seven years, you know, especially as we saw groups like ISIS starting to use drones and now especially in this conflict, the significant impact that drones have.”

Ryder cautioned, however, that the drones would likely not arrive until late spring or later, well after the fighting is expected to pick up. He declined to specify either precise numbers or timing of deliveries.

Drones to Come

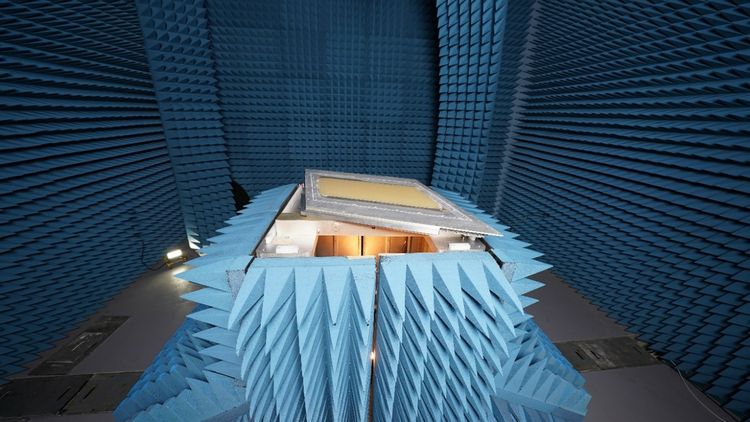

ALTIUS-600 is a small drone that can fly over 270 miles. Its manufacturer Area-I, a subsidiary of defense startup Anduril, promotes the craft as a modular system with a nose cone that can be fitted with an array of sensors or payloads. The drone is tube-launched and recoverable. The U.S. Army has tested the system in multiple forms, including launching them from the ground, from helicopters as air-launched effects (ALE), and even operating together in swarms. ALTIUS has also been tested as an electronic warfare platform. Anduril says the company has recently added a loitering munitions capability to the platform. It is unclear exactly what payloads and launchers Ukraine will receive along with the drones.

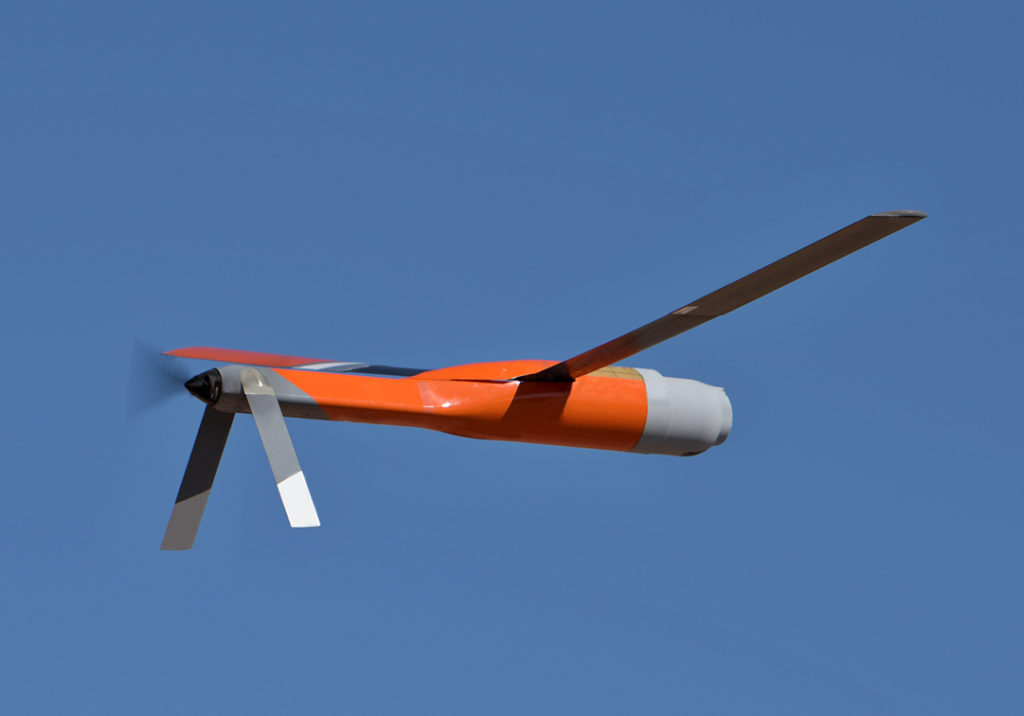

The AeroVironment Jump 20, is a vertical take-off and landing drone that can perform surveillance missions for over 14 hours with a range of around 115 miles, according to its manufacturer. It has already been fielded for U.S. Special Operations Forces, and the U.S. Army has awarded a $8 million contract to begin to purchase Jump 20s to perform tactical missions for American troops. Its design appears conventional with fixed wings and a propeller at the front. But it also features smaller propellers that are vertically mounted, which eliminates the need for runways and is one of its selling points.

The Switchblade 600 has a longer range and bigger warhead than the tube-launched Switchblade 300 drone already used by Ukraine. Like the Jump 20, it is made by AeroVironment. The Switchblade 600 can carry a 30-pound payload around 25 miles for about 40 minutes, making it well suited for anti-armor missions.

“Patented wave-off and recommit capability allows operators to abort the mission at any time and then re-engage either the same or other targets multiple times based on operator command,” says AeroVironment.

Little public information is available about the CyberLux K8, produced by 23-year-old Cyberlux Corp. Among the company’s products are small quadcopters, a type of drone that Ukraine has already extensively employed.

Lee cautioned against concluding that these new systems signal a new way of waging war for the U.S., saying instead the systems could prove useful in specific situations.

“The threat environment really hasn’t driven us toward some of the smaller commercial solutions. But I think we’re starting to see the value of doing that for allies and partners,” said Lee. “The kinds of technologies that we’re seeing have some success in Ukraine are probably not the same kinds of technologies that the U.S. might need were we to engage directly in a conflict with a peer adversary like China.”

Notably missing from the new-U.S. provided drones is the MQ-9. Ukraine has asked for Reaper drones, and its manufacturer, General Atomics, has pledged to provide them from its own stocks.

“Imagine if Ukraine had access to UAVs that had an order of magnitude more payload, twelve times the range, the ability to fly across the entire county of Ukraine and stay aloft for over a day,” said retired Lt. Gen. David A. Deptula, dean of the Mitchell Institute. “I’m talking about the MQ-1 Gray Eagle and MQ-9 Predator, of which the U.S. has dozens sitting in storage crates in the western desert not in use, or planned for use, by any U.S. agency.”