The ‘Hawks’ of the 6th Attack Squadron train pilots and sensor operators how to fly the MQ-9 Reaper drone at Holloman Air Force Base, N.M. There are six stars and six lines indicating the speed of the goshawk mascot as it drops a Hellfire air-to-ground missile. (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

The 19th Space Defense Squadron, based at Naval Support Facility Dahlgren, Va., honors its Navy ties with the ‘Space Kraken’ embracing the Space Force Delta. The three stars represent the unit’s connections to the Air Force, Space Force, and Navy, a unit member told Air & Space Forces Magazine. (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

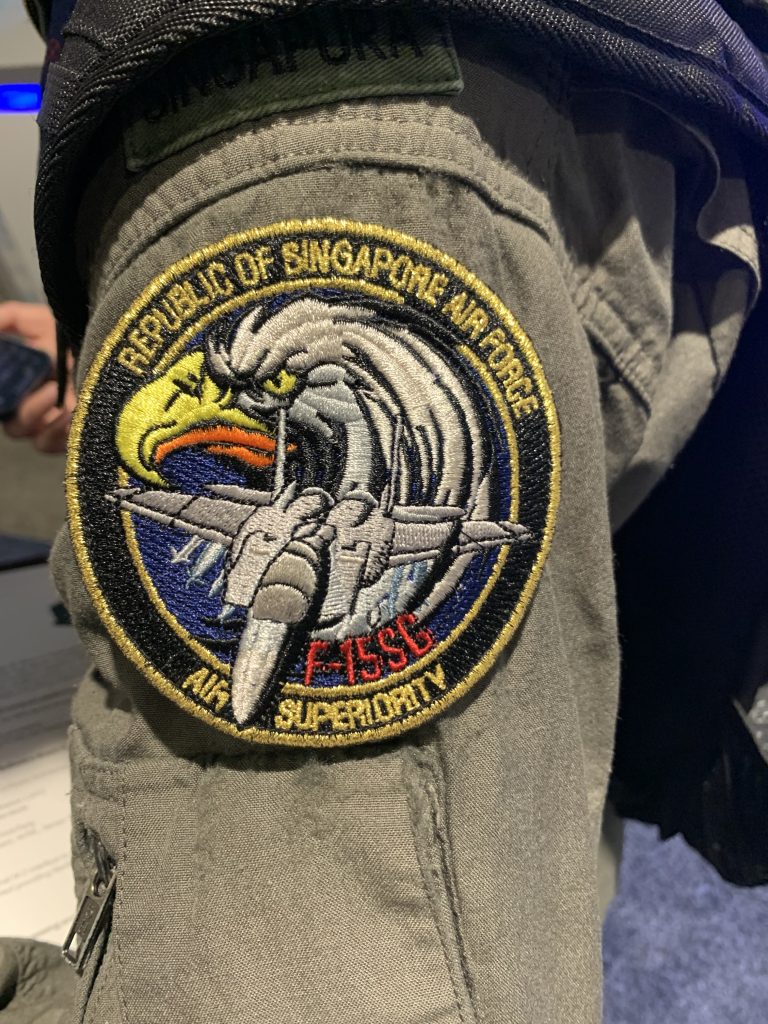

The Republic of Singapore Air Force’s 149 Squadron flies the F-15SG, a variant of the F-15E Strike Eagle. The unit has a history of winning the RSAF’s ‘Best Fighter Squadron’ Award, according to The Straits Times. (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

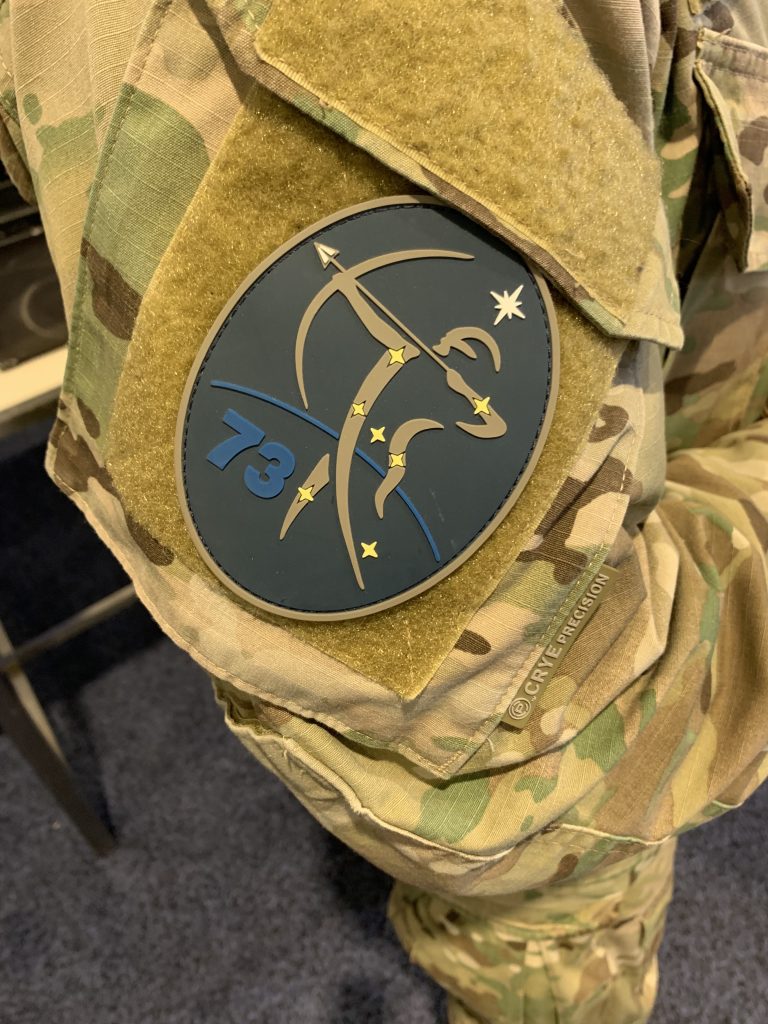

The “Space Hunters” of the Space Force’s 73rd Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) Squadron observe targets and other points of interest with the vigilance of a hunter. (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

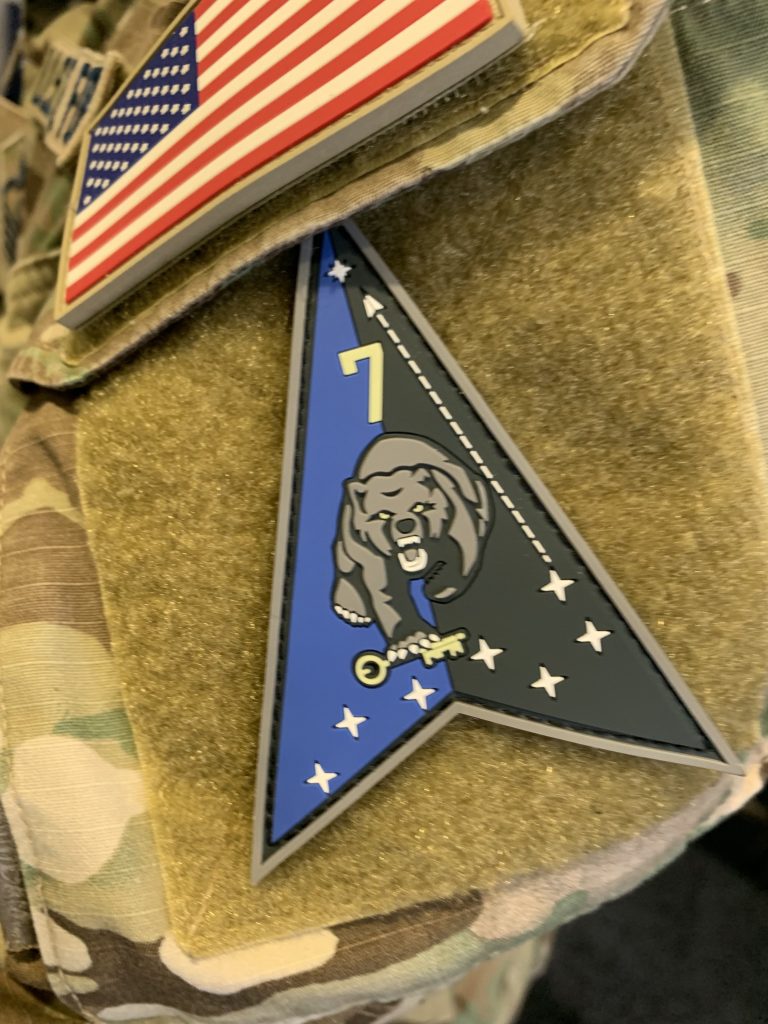

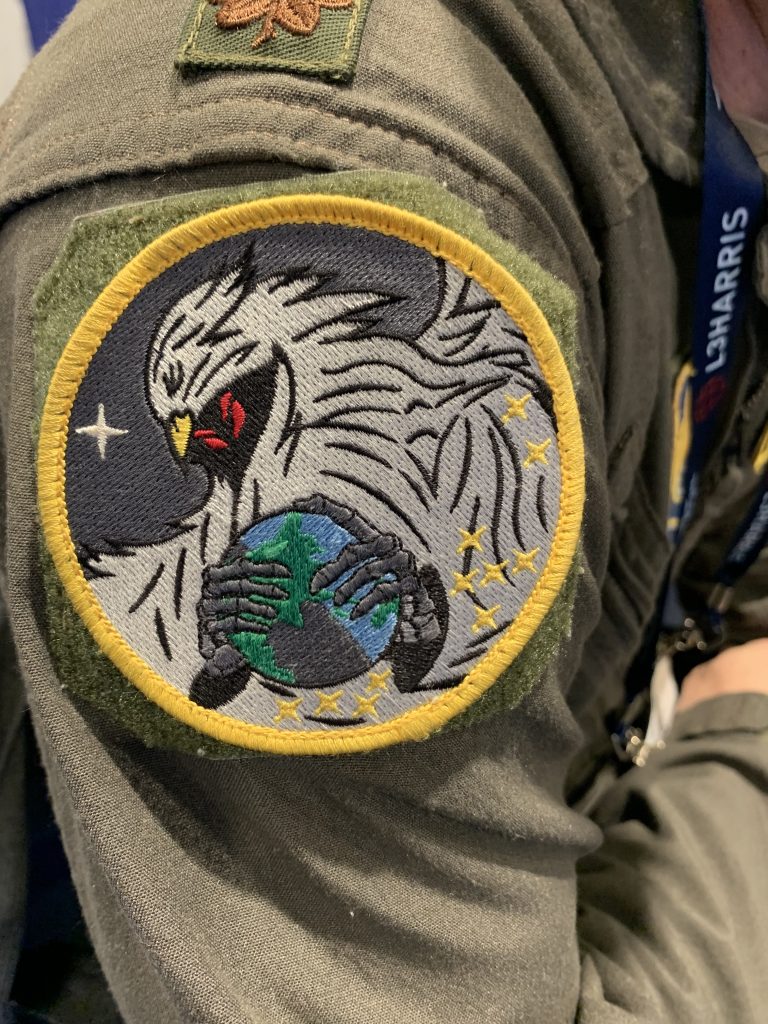

Space Delta 7 oversees the Space Force’s ISR efforts. The black and blue colors represent the unit’s orbital, airborne, and terrestrial aspects, the 7 stars form the constellation Ursa Major ‘Great Bear,’ the bear itself symbolizes “unyielding tenacity,” and the key it holds is a common emblem of the intelligence community, which seeks to “unlock” the adversary’s secrets, according to the Space Force. (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

The Travis Air Force Base, Calif.-based Phoenix Spark innovation cell empowers Airmen to use computer-aided design, 3D-printing, software coding, small drones, and other technologies to solve problems and accomplish their mission. (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

The 60th Aeromedical Evacuation Squadron has a long history of moving sick or wounded patients to higher care. Pegasus, the mythological flying horse, helped carry the Greek god Zeus’ thunderbolts, symbolizing the 60th AES’ duty to transport injured service members. The rainbow represents the unit’s mission, which often occurs after the storm of battle has passed. Semper Primus means ‘always first’ in Latin. (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

The Air Force F-35 Integration Office oversees the jet’s operational integration across the service and represents the Air Force when working with the F-35 Joint Program Office. (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

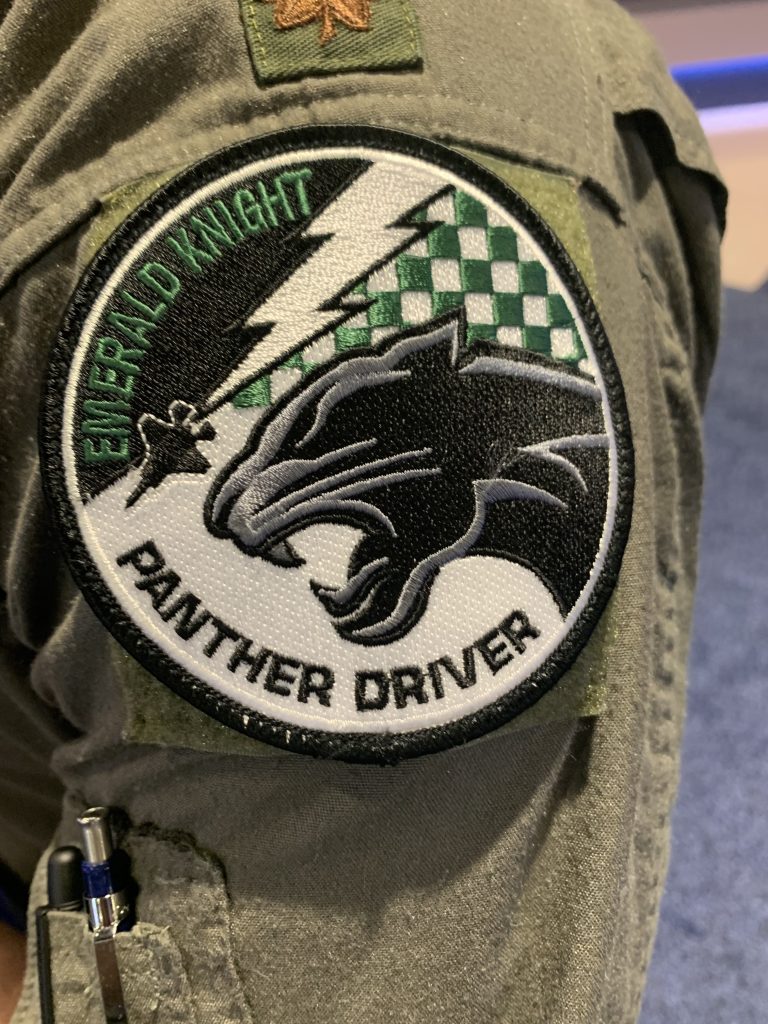

‘Panther’ has emerged as the unofficial nickname for the F-35 Lightning II fighter jet, as demonstrated by this patch worn by visiting ‘Emerald Knights’ of the 308th Fighter Squadron, an F-35 training unit at Luke Air Force Base, Ariz. (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

Only pilots who have flown the U-2 Dragon Lady reconnaissance jet solo can wear this patch. The ‘1500’ represents this pilot’s flight hours in the U-2, while the phrase ‘solum volamus’ means ‘We fly alone.’ (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

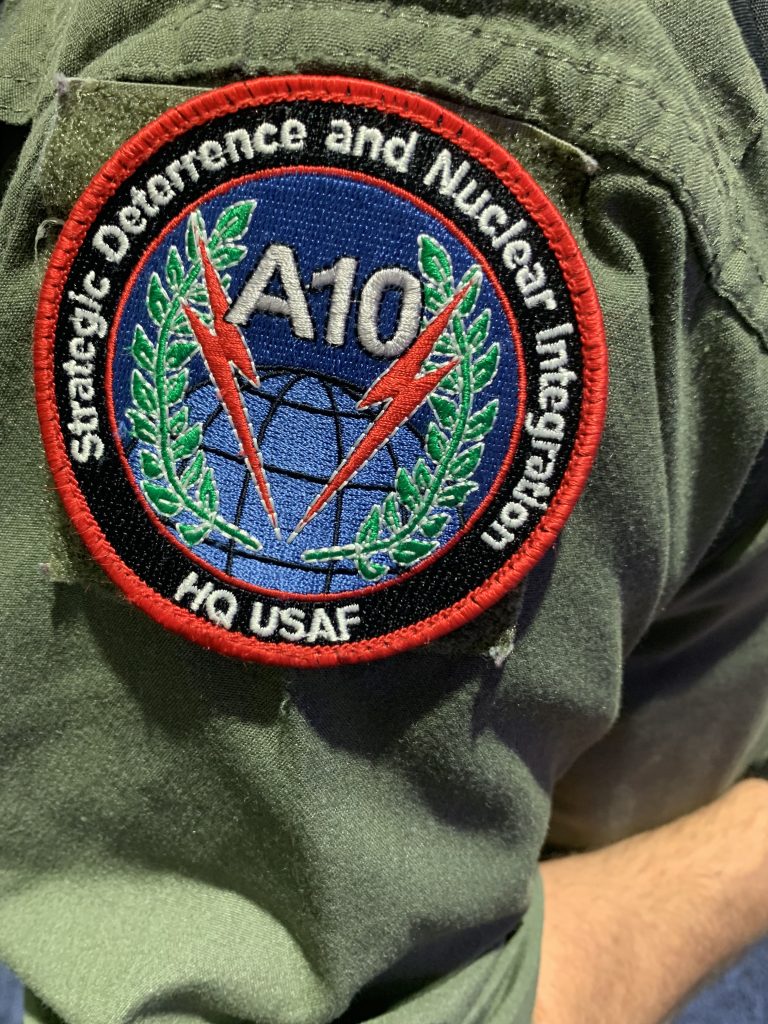

Not to be confused with the A-10 Thunderbolt II attack jet, the ‘A10’ Strategic Deterrence and Nuclear Integration Office is a Headquarters Air Force position that oversees the Air Force’s nuclear weapons systems and works with the rest of the military and the government on a range of nuclear-related missions. (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

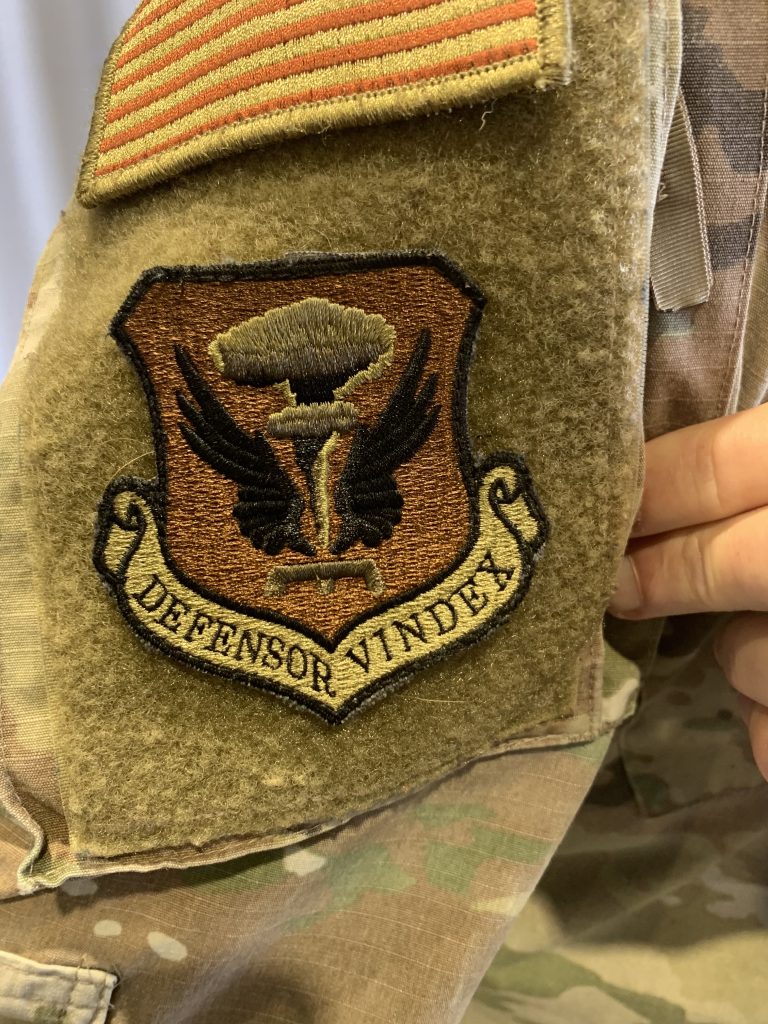

The 509th Bomb Wing flies the B-2 Spirit, a stealth bomber capable of carrying nuclear weapons. The unit dates back to World War II, where it dropped the first atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan. The mushroom cloud represents that mission, the upside-down ‘E’ is a symbol from European heraldry which means eldest son, symbolizing that the 509th is the oldest atomic-trained military unit in the world. ‘Defensor Vindex’ means ‘Defender avenger,’ as nuclear weapons can be used to “protect and retaliate” according to the wing website. (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

The patch of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations of the U.S. Air Force, often referred to as the A3, reflects how the position oversees the branch’s operations across air, space, and cyber domains. (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

The history of the 41st Intelligence Squadron dates back to the 1950s. The key is a common symbol of intelligence units, but the reasons behind the Viking helmet and ax were not immediately clear. (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

Only about 100 Airmen have graduated from the 315th Weapons Squadron, the Air Force’s ICBM weapons school, but this patch-wearer is the 95th graduate. Though the symbolism of the skeleton was not immediately clear, it sure looks great. (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

Another former World War II bomber squadron, the 452nd Flight Test Squadron most recently flew the RQ-4 Global Hawk reconnaissance drone. The squadron is assigned to Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

Originally a World War II bomber squadron, the 586th Flight Test Squadron now tests advanced weapons, sensors, and other technology while flying modified T-38C jet trainers and C-12 turboprop aircraft out of Holloman Air Force Base, N.M.(Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

The F-15E Strike Eagle can attack air and ground targets in all weather in the day or night, and that ‘anytime, any place attitude’ is captured in this ‘day/night’ F-15E patch. (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

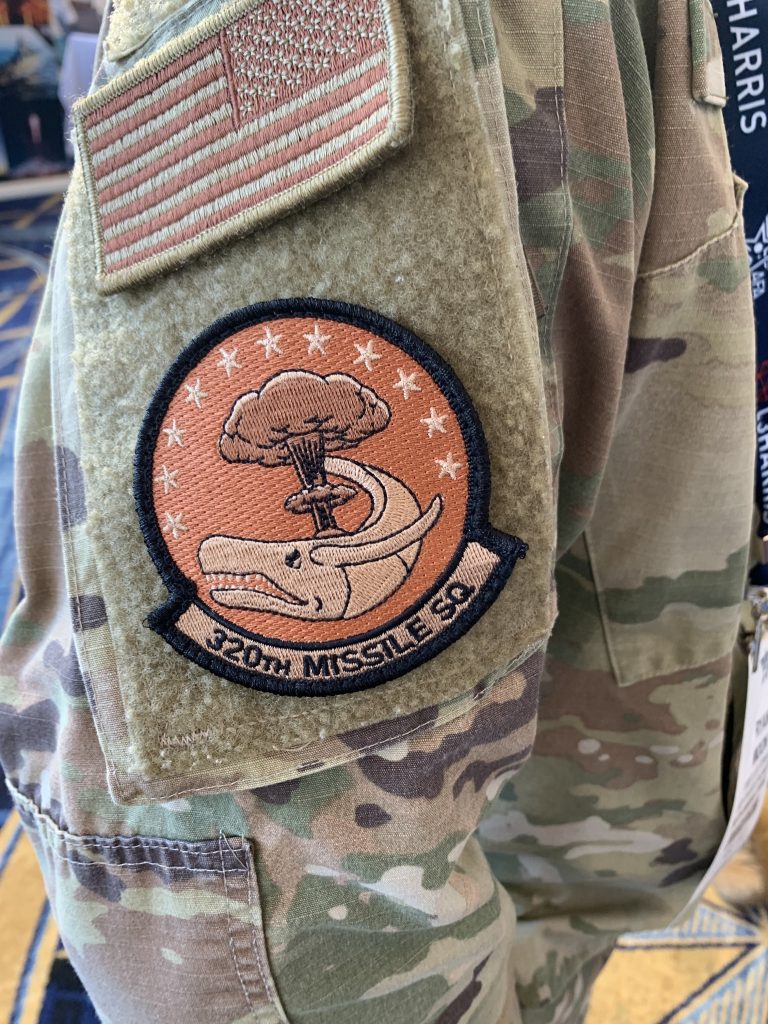

Like the rest of the ‘Jolly Rogers’ of the 90th Missile Wing at F.E. Warren Air Force Base, Wyo., the 320th Missile Squadron started as a World War II B-24 bomber squadron. According to a unit history, one B-24 nicknamed ‘Moby Dick’ downed four Japanese planes, sunk three ships, and at one point returned from a mission with 200 large bullet holes. (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

The Greek Titan Atlas had a heavy responsibility holding up the heavens for eternity, and so do members of Striker Titan, a professional development program that provides graduate-level education on the Air Force global strike enterprise for noncommissioned officers. (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

A tentacled version of the ‘mighty watchful eye’ celebrated in the Space Force official song appears in this patch for the intelligence collection management component of the Combined Space Operations Center at Vandenberg Space Force Base, Calif. (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

Each flight of the 37th Intelligence Squadron has a different shark mascot, like hammerheads, bull sharks, or, in this case, dog sharks. (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

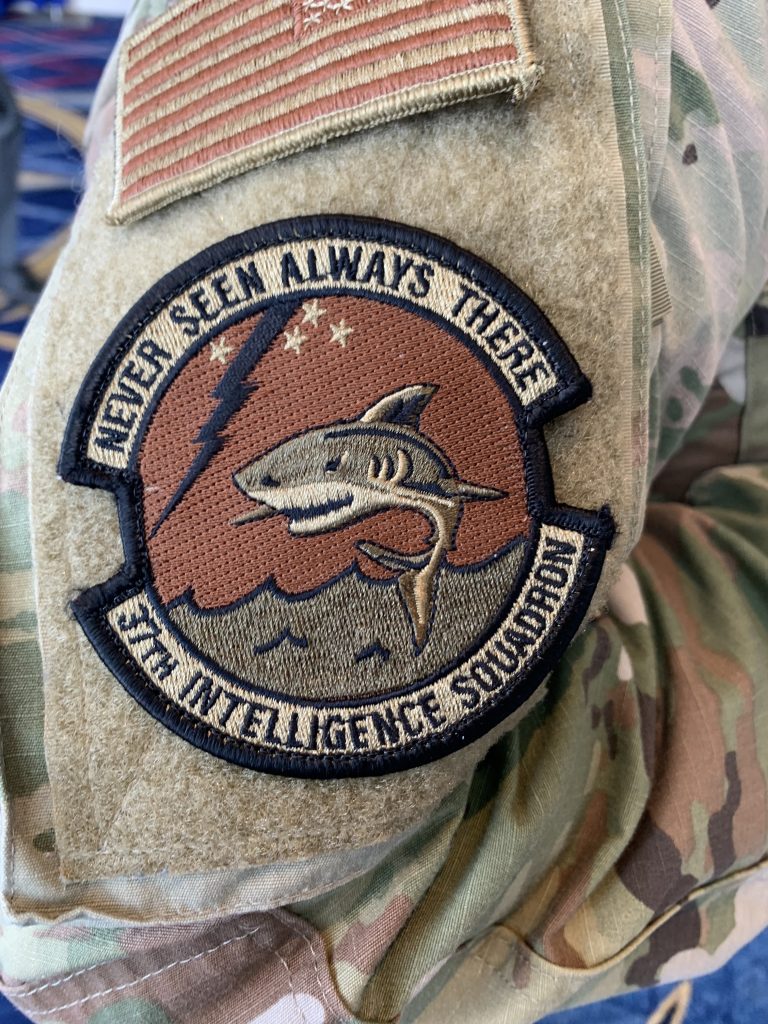

A bit like the great white sharks that sometimes swim off the coast of its home at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii, the 37th Intelligence Squadron is ‘never seen, always there.’ (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

Activated in 2020, the ‘Krakens’ of the 39th Electronic Warfare Squadron at Eglin Air Force Base, Fla., work a range of spectrum warfare missions, like testing new software and closing caps between the intelligence community and the combat Air Force. ‘Vigilamus ab umbris’ means ‘We watch from the shadows.’ (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)

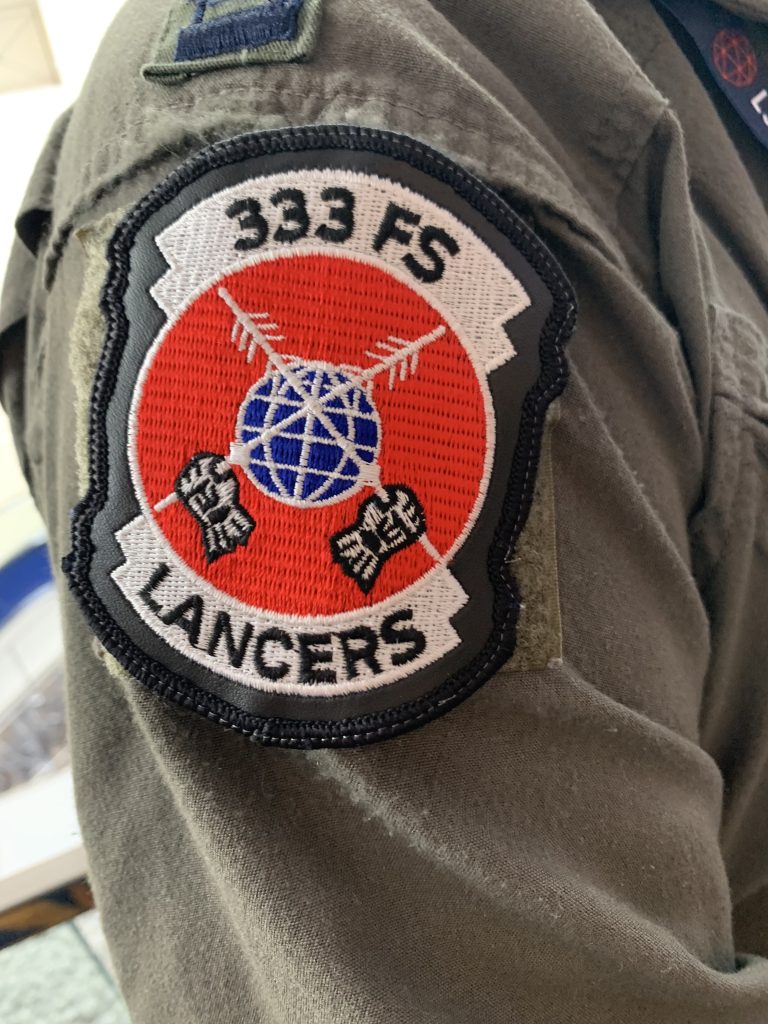

The ‘Lancers’ of the 333rd Fighter Squadron flew combat missions over Vietnam before training pilots of close air support aircraft like the A-7 Corsair II and A-10 Thunderbolt II. Today, the 333rd is a formal training unit assigned to Seymour Johnson Air Force Base, N.C., where it qualifies F-15E Strike Eagle pilots and weapon systems officers. (Air & Space Forces Magazine photo by David Roza)