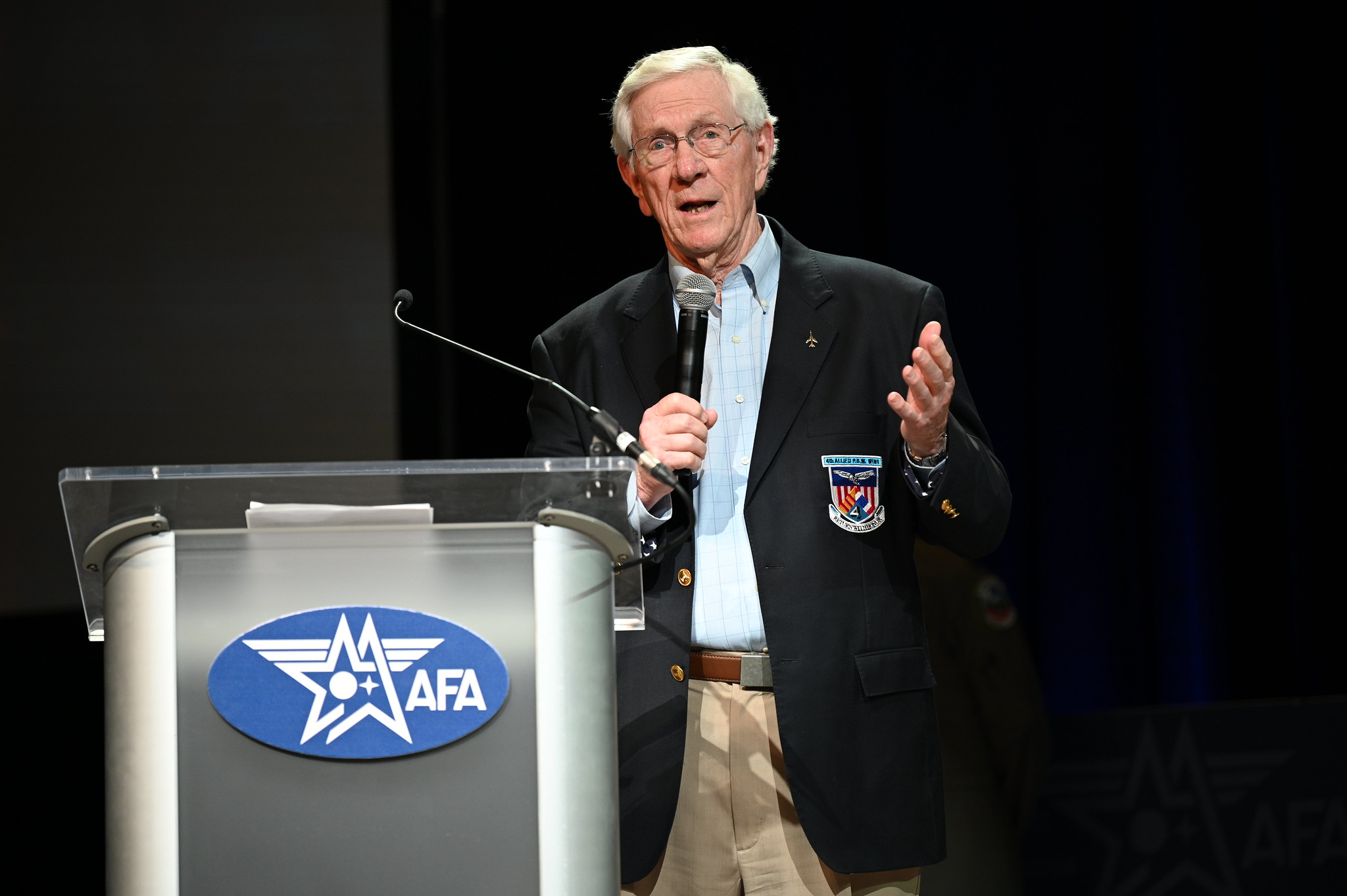

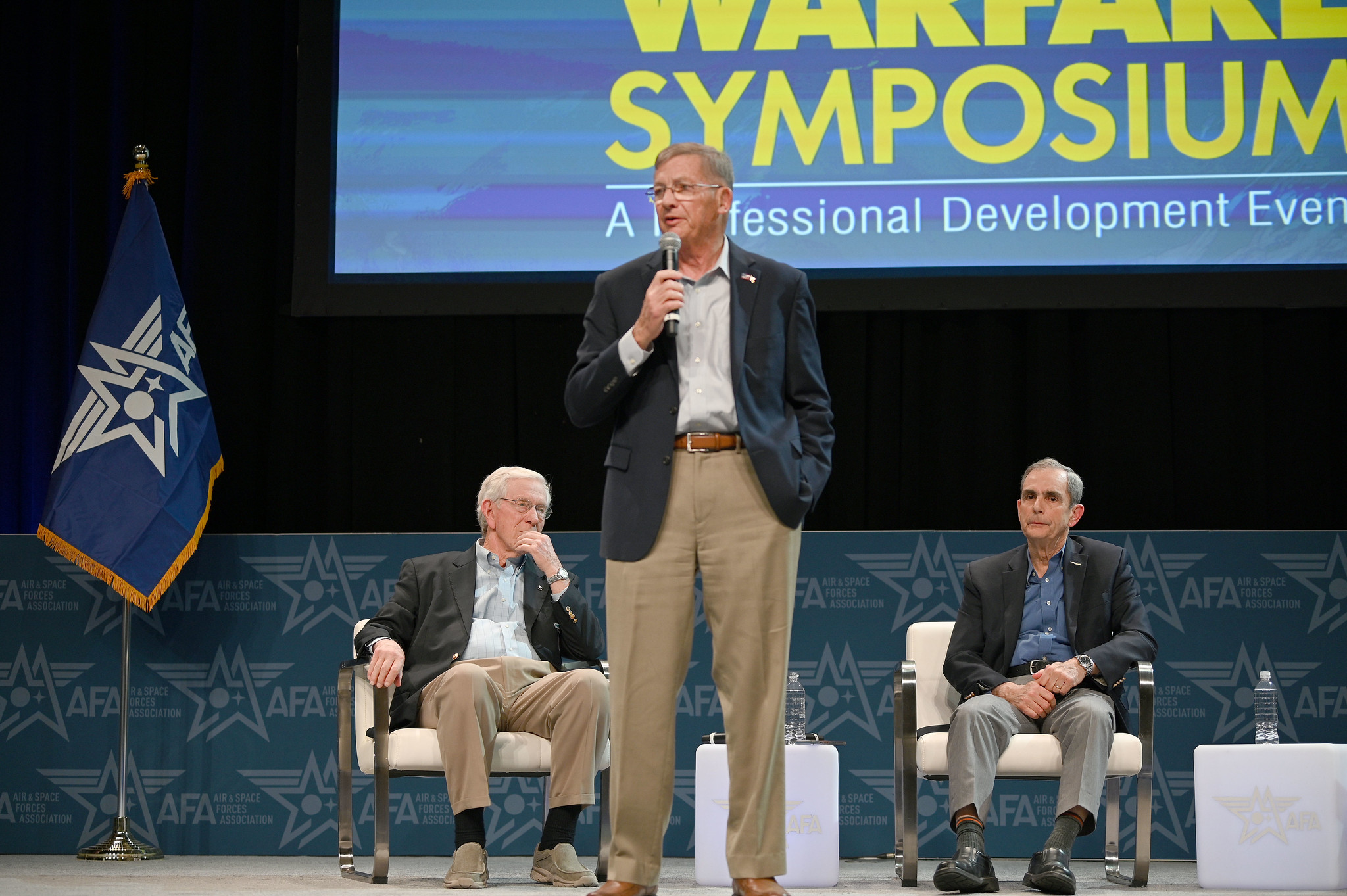

The AFA Warfare Symposium kicked off March 6 with three storied heroes of the Vietnam War. This is the first in a three-part series on their talks.

Lt. Col. Gene Smith (Ret.). Smith joined the 333rd Tactical Fighter Squadron at Takhli Royal Thai Air Base, Thailand, in August 1967. For the next two months, Smith flew 33 combat missions in his F-105 Thunderchief over North Vietnam. His 33rd mission, Oct. 25, 1967, struck Phúc Yên Air Base, just north of Hanoi. It was his last.

“We took off that day, a beautiful afternoon,” Smith recalled. As the flight lead, he had carefully briefed his team to drop their bombs at 9,000 feet, no higher. “Guess who exceeded the 9,000 feet? Me. And when I pulled off the target my airplane got hit. Instantly, the airplane tumbled.”

Pitching uncontrollably, Smith bailed out awkwardly, sustaining a deep flesh wound in his right leg as he exited the cockpit. His parachute opened and he descended; as soon as his feet touched the earth, he was surrounded. Vietnamese soldiers armed with AK-47s fired, sending two bullets ripping through his left leg.

“They undressed me with a machete and off we went to the Hilton,” Smith said, referring to the notorious Hoa Lo prison known eupemistically as the Hanoi Hilton. It would be his home for the next 1,967 days, where he and hundreds of other Airmen prisoners endured interrogation and torture.

“We spent five and a half years,” Smith said. “That’s the hardest part to understand about our conditions, is how long it was. The horrible indefiniteness of it all.”

Smith returned as part of Operation Homecoming on March 14, 1973; in all, 591 Americans came home as part of the operation between Feb. 12 and April 4 of that year.

Surviving was the true test of the their endurance.

“You can’t teach resiliency,” Smith said. “You can teach some of the factors in the equation. But you learn resiliency as a child. You learn resiliency when you’re in high school or college. You learn resiliency in your first days in the military, I hope. But the way we got through that was faith. Faith in God. Faith in your country. Faith in your family, that they would always be there for you. Faith in your fellow POWs.”

The faith that helped Smith withstand the darkest years of his life did not lead him to a lifetime of resentment or despair, but to a lifetime of service and repayment to his nation and his Air Force.

“The most beautiful flag I’ve ever seen in my life was on the tail of a C-141 that pulled up into Gia Lam and took me, Lee Ellis, John McCain, Chuck Rice, and a whole list of others that were in that group,” Smith said. “I shall always be grateful. I shall always be grateful to my nation. I shall always be grateful to the Air Force for the wonderful life I’ve had.”