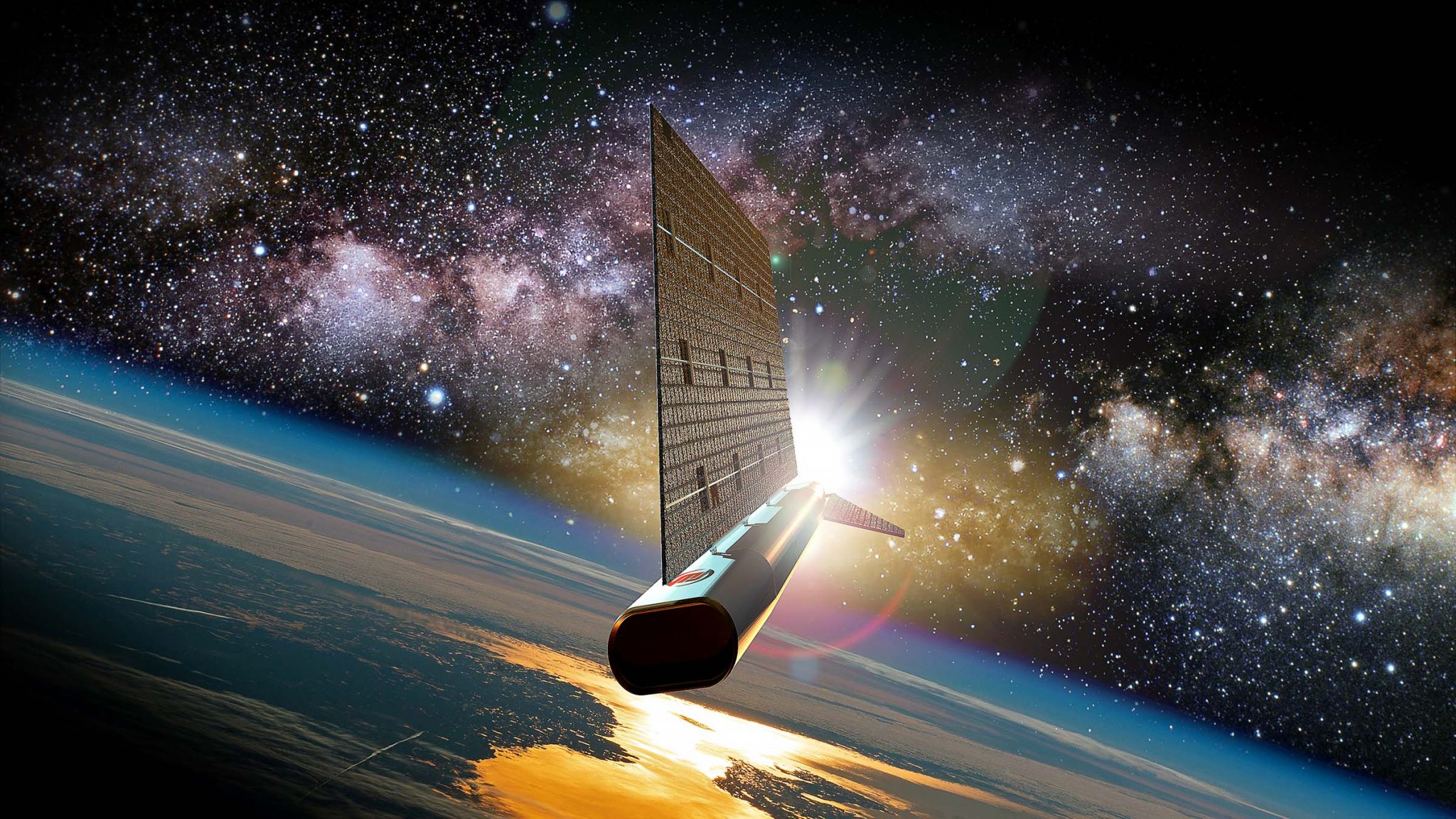

Lockheed Martin is developing a second version of its Common Multi-Mission Truck (CMMT) system—a low-cost vehicle meant to carry a variety of payloads—and both variants have been tested successfully in recent weeks, the company said.

The larger of the two designs is the CMMT-D, an unpowered glide vehicle, and the smaller is the CMMT-X, which has a motor. The CMMT-D was dropped vertically from a pallet, as would be used from a cargo aircraft, while the new CMMT-X was pylon-launched from the bottom of a small aircraft. The “D” stands for “Demonstrator,” while the “X” indicates “it is an X-plane and experimental variant of CMMT,” a Lockheed spokesperson said.

The company rolled out CMMT-D in March at the AFA Warfare Symposium, saying it has been pursuing the concept of a low-cost cruise missile-type vehicle for some time, to complement its very stealthy, high-end AGM-158 Joint Air-to-Surface Missile. The company said the CMMT-D has a range of about 500 nautical miles range and can be configured “to launch from fighters, bombers and ground launchers.”

The two new vehicles are aimed at a broad military requirement for low-cost standoff munitions, and Lockheed is pursuing pylon-launched, pallet-launched, and vertical launch variations. The CMMT-D is intended to have a unit cost of about $150,000—10 times less than a JASSM. Unlike the JASSM, though, the CMMT isn’t meant to be ultra-stealthy, and the company envisions building the vehicle “at scale.”

The two CMMTs appear to be sized and priced roughly in line with the Air Force’s Family of Affordable Mass Missiles (FAMM), but Lockheed is not among the competitors for that program. Anduril Technologies and Zone 5 Technologies are the competitors for FAAM, which will be launched using Rapid Dragon-type techniques. The Air Force is looking to build more than 3,000 FAAMs in 2026 alone. The Pentagon has not released out-year information in its fiscal 2026 budget request, but service officials have suggested future buys may be similar.

“Lockheed Martin engineers starting development on both models less than a year ago,” the company said in a press release. “CMMT-D is the first compact affordable cruise missile in industry to deploy from Rapid Dragon, while CMMT-X achieved powered flight in its first flight.”

The CMMT-D was tested from a Rapid Dragon-type pallet cell—the same style the Air Force has used in recent years to drop pallets of inert JASSMs from the back of a cargo aircraft like the C-17 or C-130H. In May, the pallet was suspended from a helicopter at an altitude of 14,500 feet over the Tillamook UAS Tet Range, Ore., simulating a parachute descent from a fixed-wing airlifter. The CMMT-D deployed it wings and made an unpowered glide to the surface.

This was the “first deployment of a compact air vehicle in a tactically representative airborne environment,” the company said.

From concept design to first flight was 10 months, Lockheed said, noting that it also carried out the first Rapid Dragon test from “clean start” to test in 10 months.

A month later, the new CMMT-X was mounted to a pylon under a Piper Navajo civil turboprop flying over the Pendleton UAS Range in Ore.; it safely separated from the aircraft, deployed its wings and its engine lit for powered flight. Lockheed said the CMMT-X is the direct descendant of its 2020 “SPEED RACER” concept, which began exploration of “expendable-class systems.”

The CMMT-X has a range of about 350 nautical miles, Lockheed said.

The two vehicles have been designed using digital methods to demonstrate speed from concept to fabrication, but also in potential production.

Lockheed said it took half the usual time to go from concept to preliminary design review on the CMMTs, helped by previous work on SPEED RACER and digital techniques.

While the Air Force has not yet settled on what characteristics Increment 2 of the Collaborative Combat Aircraft program will have, the CMMT’s “flight-tested design and developed architecture could be quickly adapted for low-cost [CCA] applications should those requirements move forward,” Lockheed said.