The U.S. military announced Dec. 6 that it is standing down its entire fleet of Ospreys after eight Airmen were killed in a crash.

The Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy are all standing down Osprey operations after an Air Force Special Operations Command CV-22 crashed off the coast of Japan on Nov. 29—a fleet of hundreds of aircraft.

The Air Force said initial findings suggested there was a “material failure” with the Osprey, indicating pilot error was likely not the primary cause and there was an issue with the aircraft itself.

“The underlying cause of the failure is unknown at this time,” AFSOC added in a statement.

AFSOC’s commander Lt. Gen. Tony Bauernfeind directed the standdown to “mitigate risk while the investigation continues,” the statement added. “The standdown will provide time and space for a thorough investigation to determine causal factors and recommendations to ensure the Air Force CV-22 fleet returns to flight operations.”

Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR), which is in charge of both the Navy and Marine Osprey fleet, released a nearly identical statement.

“While the mishap remains under investigation, we are implementing additional risk mitigation controls to ensure the safety of our service members,” NAVAIR added.

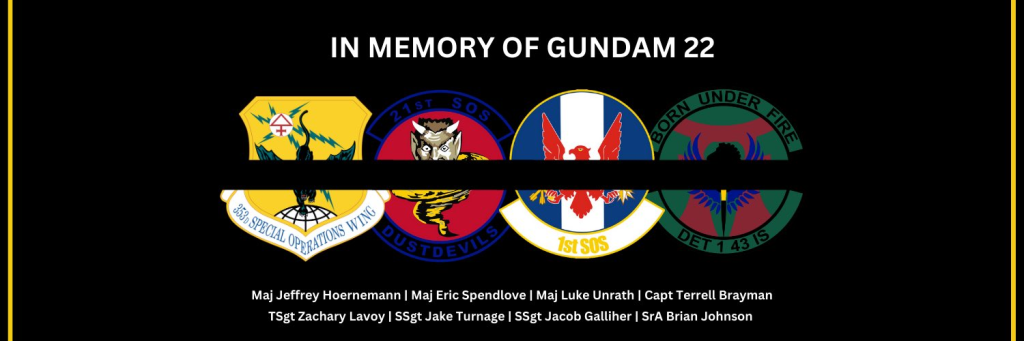

The aircraft that crashed Nov. 29 caught fire and fell into the ocean near Yakushima, Japan. The U.S. military and the Japanese military, coast guard, law enforcement, and civilian volunteers, including local fishermen, conducted a massive search and rescue effort. The bulk of the wreckage was discovered by surface ships and dive teams on Dec. 4. Six Airmen’s remains have been recovered. The bodies of two Airmen have yet to be recovered.

Japan grounded its fleet of 14 Ospreys soon after the crash. The Air Force has around 50 Ospreys. The Department of Navy, which includes the Marine Corps and the Navy, operates more than 300 Ospreys, the bulk of which belong to the Marines.

The Osprey is a tilt-rotor aircraft, which allows it to take off and land like a helicopter, then move its rotors and fly like an airplane.

The U.S. military services coordinate together on the Osprey through a joint program.

“The Joint Program Office continues to communicate and collaborate with all V-22 stakeholders and customers, including allied partners,” NAVAIR said.

Shortly before the standdowns were announced, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) called for the aircraft to be grounded during a congressional hearing.

“While we all accept that there are risks that come with fighting the enemy on the battlefield, I am concerned that too many service members are receiving lasting injuries or losing their lives due to accidents,” said Warren. “In fact, accidents have been one of the leading causes of death for active duty service members.”

Warren said she still wanted to see the Osprey fly again, but only after “we can be confident that we won’t lose any more lives in what appears to be a preventable tragedy.”

The crash was the deadliest Air Force aviation mishap since 2018, when nine Air Guardsmen were killed in a WC-130 crash in Georgia. It is also the deadliest ever Air Force CV-22 accident and the first since 2010. In August, three Marines were killed when their Osprey crashed in Australia. In 2022, nine Marines were killed in two separate crashes. The latest incident raised fresh questions about the fleet.

This is the second time in a little over a year the Air Force has grounded its Osprey fleet. A series of hard clutch engagements—in which the clutch slips and reengages, which caused USAF Ospreys to make emergency landings—led then-AFSOC commander Lt. Gen. James C. “Jim” Slife to order a temporary standdown in 2022.

“We continue to gather information on this tragic incident, and we will conduct a rigorous and thorough investigation,” Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III said in a Dec. 5 statement.