In the months following the reveal of Northrop Grumman’s B-21 Raider in December, several publications affiliated with the Chinese Communist Party or its People’s Liberation Army published articles downplaying the aircraft’s viability, saying the U.S. cannot afford enough of the bombers to make a difference in a possible conflict with China.

And while that view may not represent a consensus within the PLA, it does give U.S. policymakers a hint of how China views one of the cornerstones of future U.S. airpower.

“We could certainly change their calculations and force the optimists to have to come up with a better argument if we don’t meet their expectations and produce the B-21 in large numbers,” Derek Solen, a senior researcher for Air University’s China Aerospace Studies Institute, told Air & Space Forces Magazine. “They would really have to sit down and assess the B-21’s capabilities and whether they can counter it.”

In a recent study for CASI, Solen analyzed media reactions within China to the B-21’s unveiling. One of the more dismissive analyses appeared in the global military section of Liberation Army News, which Solen described as “the mouthpiece” of the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Military Commission.

The writers argued the B-21 may be “strategic blackmail,” meaning the bomber’s main purpose is to force opponents to devote inordinate resources toward developing countermeasures for it. The writers claimed that the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber was also intended to “drain the Soviet Union’s military and economic strength.”

Indeed, as the B-2 approached production in the late 1980s, the aircraft was expected to create dilemmas for Soviet military planners, though Solen said that was likely a secondary effect of the B-2’s design rather than its primary purpose.

“How will the Soviets respond to the U.S. stealth challenge?” wrote one observer in the 1989 edition of the journal International Security. “Will the Soviets divert substantial resources to air defense to counter stealthy air vehicles?”

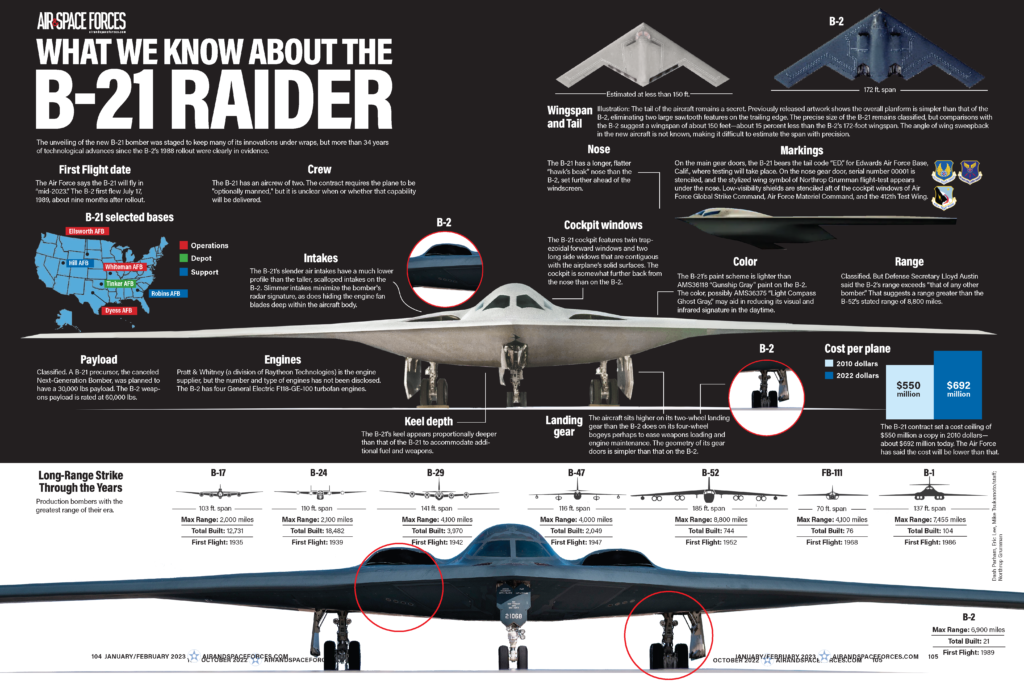

After the Soviet Union collapsed, Congress reduced the purchase of the B-2 from 132 aircraft to 75 to just 21. Three decades later, the B-21 is expected to cost about $660 million each, and Air Force officials hope to buy 100 copies. The Liberation Army News writers predicted the B-21 program would not achieve economies of scale, due to its “astonishing” total cost—and therefore it would be difficult to achieve any “strategic effect.”

Solen found other publications made similar assessments. An article published in the military weekly section of China Youth Daily said the U.S. Air Force may not have the budget to afford many B-21s and would ultimately “walk in the trail of the B-2.” The writers added that the B-21 would also have difficulty “when facing a great power possessing a relatively perfect counter-stealth sensor network and air defense system … without being detected and intercepted.”

A third publication, Chinese National Defense News, wrote that the B-21’s stealth capabilities are not advanced enough to infiltrate modern radar systems and the U.S. Air Force would not be able to afford enough of them.

A fourth publication did differ from the other three in taking a more cautious position. The science and technology section of Chinese National Defense News tends to eschew “political messages in order to introduce foreign technological advances,” Solen wrote.

The author, Xin Qizhi, wrote that the B-21’s main advantage over the B-2 is that the Air Force can afford more of them, and Xin urged readers not to treat the threat lightly.

“Overall, all the authors besides Xin expressed doubt that enough B-21 bombers will be acquired to compensate for their expected losses due to advances in radar,” Solen wrote. “The question that this ostensible difference raises is which side represents the prevalent opinion in the PLA.”

Critical Self Assessments

The Chinese Communist Party does not tolerate free speech, so even if the B-21 worried PLA officials, would non-Chinese researchers be able to access that information? They might be able to: RAND senior international defense researcher Mark Cozad said that, like most professional militaries, the PLA conducts critical self-assessments that can be found in academic military publications or technical journals.

“There is a lot you can find out, at least in terms of what they think about themselves,” said Cozad, who was the lead author on a RAND report published earlier this year about Chinese perspectives on the military balance between the U.S. and PLA. “And I think in most respects, they’re very realistic. They definitely don’t have a hard time criticizing themselves.”

Just like in U.S. military journals, those publications may not include sensitive details on platforms or capabilities. In the PLA, they also tend to focus on operational concepts and steer clear of broader defense policy issues that are decided by high-level party leadership. But they do analyze lingering issues affecting the PLA and options for what to do about them.

“These are the things that the PLA is telling themselves about themselves,” Cozad explained. “You’ll see the discussion of the problem, you’ll see proposed policies or programs, and you’ll see how those things evolve over time.”

Those nuanced discussions may not appear in publications like Liberation Army News, which tend to produce propaganda, Cozad said. Still, even propaganda can provide helpful information.

“Just because it’s crafted doesn’t mean that the people who are crafting it don’t believe what they are saying,” Solen said. “And just because someone like Xin, who’s sounding a different note, is saying the thing that we kind of want to hear doesn’t mean that he’s a truth-teller.”

Indeed, American airpower policy experts are also arguing the Air Force needs to up its proposed production rate of B-21s to provide the long-range power projection necessary to deter China.

Doubling the bomber’s production rates and reducing unit costs “would require difficult force structure trades” if the Air Force budget remains static, wrote Dr. Christopher J. Bowie, non-resident senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, in a report published March 10.

“The Air Force needs to field more long-range bombers, which appear to offer significantly greater utility and reduced basing vulnerability compared to short-range fighters,” Bowie wrote, arguing for a 3:1 fighter-bomber ratio similar to those seen in the 1950s and 1960s, as opposed to the 15:1 ratio that exists today. Such a shift would require retiring legacy fighters more quickly, a task the Air Force has struggled with in the past.

“If the United States continues on its current course, it could end up with a force ill-suited to the challenges posed by China,” Bowie warned.

‘Let’s Exploit That’

Despite optimistic propaganda, PLA planners may take a pessimistic view of the B-21 simply because that is the nature of many military professionals.

“In the military, more often than not, people are worst-case thinkers,” Solen said. “If America is advertising a bomber with these capabilities, the prudent thing to do is assume that it’s all true.”

And if it is true, then the Air Force can give the PLA headaches by buying a large number of B-21s, as well as maintaining the service’s other advantages over the PLA.

“You have to continue to innovate, because these guys are very serious about improving their military capabilities,” Solen said. “If the stated capabilities of the B-21 are the case, then it’s an incredible platform. Let’s not throw that away. Let’s exploit that to its fullest.”

And in the meantime, more analysis like Solen’s could give planners a better sense of what PLA officials worry about in regards to the U.S. military.

“More of that work is really needed,” Cozad said. “What I think would be helpful for a lot of planners is to understand how the adversary looks at your weapons system, whether it’s correct or not.”

If the adversary’s perception is correct, it gives planners a realistic sense of what they might expect in terms of countermeasures. If it’s not, it still could provide helpful information as the military continues to learn more about China after focusing on counterinsurgency conflicts the past 20 years.

“From a bureaucratic, big government, national security complex perspective, we’ve spent a relatively limited amount of time thinking about China,” Cozad said. “You’re learning a new target in essence: going back to the basics, looking at the numbers, the organizations, the people, the general history, and I don’t think it is always the first thing that comes to mind to study how people think about themselves, how do they think about us? … Eventually this will become a much more mature effort.”