The Air Force is pressing to find out why some Airmen and former Airmen who worked wth the nation’s intercontinental continental ballistic missile fleet are being diagnosed with blood cancer—years after the service dismissed such concerns in the early 2000s.

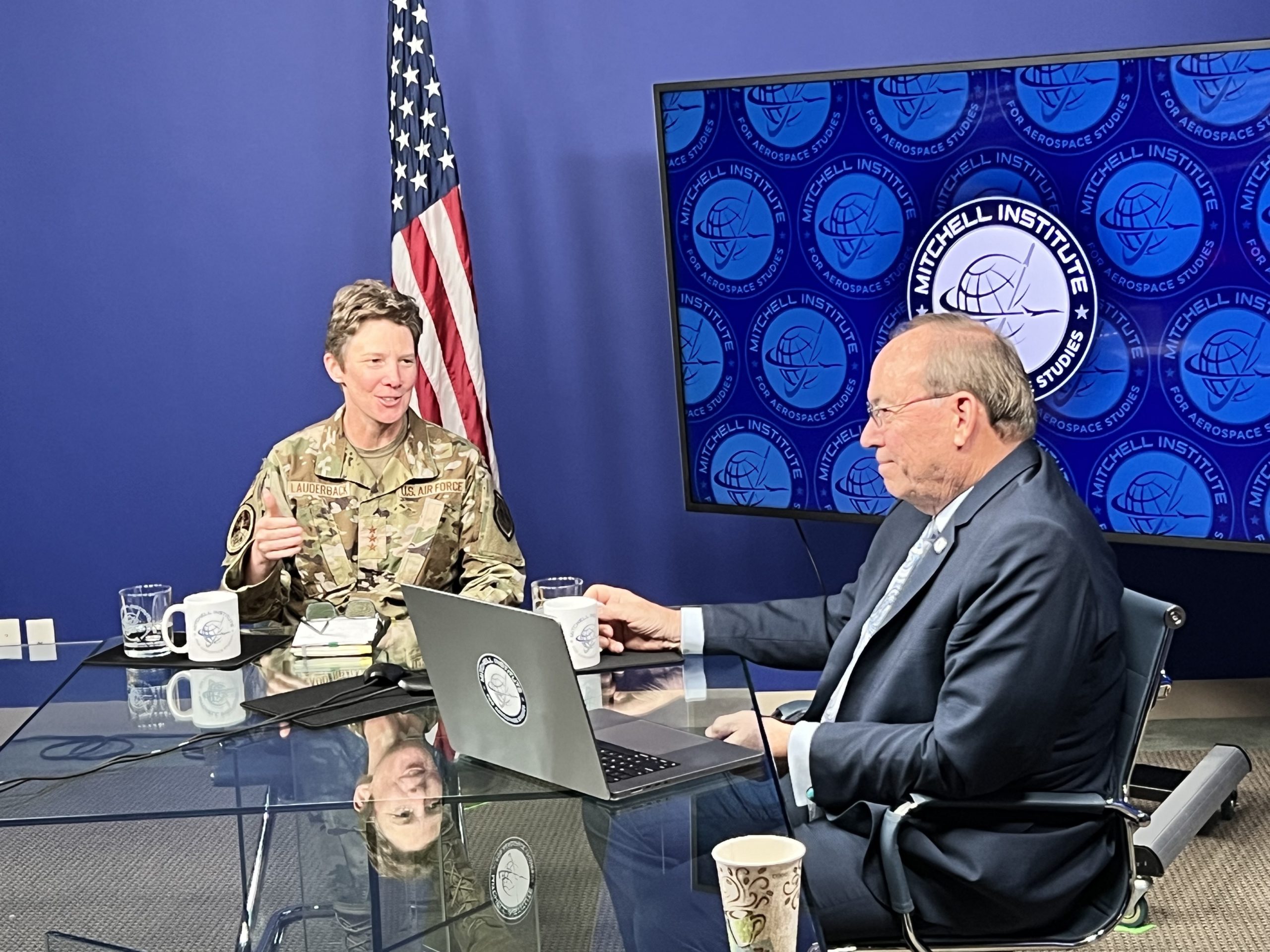

A new Missile Community Cancer Study launched earlier this year aims to “make sure we get to the truth, whatever that truth is,” said Col. Robert D. Peltzer, a senior medical officer with Air Force Global Strike Command.

Air Force reviews of cancer rates among missileers in 2001 and 2005 could not identify an increased rate linked to missile service, but new medical knowledge has emerged since, Peltzer said. Doctors have “a better understanding” of factors that can cause cancer today.

“Look at [the herbicide] Roundup being one of those,” Peltzer said. “Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is the No. 1 cancer on the list when you look at it. We didn’t know [Roundup] caused those types of cancers back in 2001.”

Armed with greater knowledge and detection capability, the Air Force will also have better access to highly classified ICBM facilities and the health data for a broader range of personnel, including both those working in underground bunkers for 24-48 hours at a time.

Peltzer said maintainers, security forces, and food service workers—among others—will also be in the new study, not just those who worked in launch facilities. Members of the study team, which is led by the U.S. Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine, visited bases to better understand the facilities and potential exposure issues.

“We want to make sure we didn’t miss out or exclude groups that actually are just as much—or potentially as much—at risk, or more at risk, than those members,” Peltzer said. The research team is made up of experts experienced in conducting cancer studies, including one that showed increased risks of cancer among pilots in recent years. That study led to a broader Pentagon review that validated the Air Force study’s conclusions.

“This is the same team and through that they learned which data sources and what they could get and how long it took them to get it,” Peltzer said.

But to conduct a study, Air Force medical officials said, they first have to know what an ICBM base is and what ICBM forces do—from an “operational, occupational, and environmental” perspective.

Col. Tory W. Woodard, commander of the USAF School of Aerospace Medicine, told Air & Space Forces Magazine that seeing the bases was a new experience for the research team. “Many of the medical experts had not previously been to a missile base or been in the operational locations where the missileers work,” Woodward said. “This visit was extremely important in order to inform the future cancer studies.”

Woodard was on the team that visited three ICBM bases— F.E. Warren Air Force Base, Wyo.; Minot Air Force Base, N.D.; and Malmstrom Air Force Base, Mont. The visit took place from Feb. 27 to March 7 and included his staff, members of the AFGSC Command Surgeon’s office, and experts from the Defense Health Agency.

“The team did not see any acute risks that needed immediate attention,” Peltzer said.

But Peltzer said there was no intention to dismiss cancer risks as they reviewed the facilities and flagged other possible medical concerns, such as running vehicles too close to air vents, burning documents indoors, or signage that indicated the presence of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), which have long been banned and should have been removed. Whether the signs were left behind after the PCBs were removed years ago is not clear. To locate traces of PCBs and a long list of other possibly toxic substances will require extensive sample testing, according to AFGSC.

ICBM facilities are often surrounded by private land where agricultural products may have been used without regard to the potential effect on missileers working nearby. The next-generation Sentinel ICBMs that will eventually replace today’s 50-year-old Minuteman III ICBMs will likely also be safer, given modern understanding. But an AFGSC official noted that even new missiles will have their own hazards.

Air Force officials said these first visits were not intended to draw definitive conclusions.

“It’s not the epidemiology study, so it wasn’t looking at cancer-related items,” Peltzer said. “That will be done later through the actual study itself.”

Interest and focused attention on the issue comes only after long-held concerns among some members of the missileer community pushed to the fore earlier this year, following a presentation detailing cases of Non-Hodgkin lymphoma at Malmstrom by a Guardian who formerly served there. His Powerpoint slides later surfaced on Facebook, prompting AFGSC Commander Gen. Thomas A. Bussiere to call for and launch the study in February.

Bussiere, Woodard, and AFGSC Command Surgeon Col. Lee D. Williames briefed members of the ICBM community at a recent virtual hall, Air Force officials said. Bussiere directed his staff to explore the idea of assigning medical professionals directly to ICBM units, modeled on how flight surgeons support flying crews. Because of the remote and classified nature of ICBM work, that could yield more real-time access to sensitive areas.

While the study is inspecting the three current active bases, which have ICBMs spread out over five states, the service is going through military, federal, and state cancer registries. The study will then have to match that data with service personnel files. That is not a straightforward process as the Air Force has changed job titles over time. The study is expected to take 12-14 months from start to finish, according to Woodard. The time is largely due to the amount of data that needs to be collected and analyzed, Peltzer explained.

“They will look at everyone possible,” Peltzer said.

A number of since-shuttered bases will also be examined as the service reaches back four decades in its data gathering process. Only the on-site work is limited to those three-active bases.

Peltzer said researchers will use Air Force Specialty Codes, bases, and timelines. “We know them all and all locations that were active since 1983,” he said. “Those members will be captured into this data study because that seems to be a great concern, especially of those who are retirees or former retirees if they’ve already passed away.”

Former and current service members have expressed skepticism over previous Air Force health studies, criticizing them for leaving the Air Force to study itself. The new study leverages epidemiologists from the Veterans Administration and the National Cancer Institute to monitor the study and provide feedback.

“There’s going to be outside entities,” Peltzer said. They “will give us a fair and objective look at what we’re doing to make sure we’re aboveboard.”