Congress should direct the Pentagon to break out the F-35’s propulsion upgrade from the rest of the program to better to track its scope, schedule, and cost, the Government Accountability Office urged in a new May 30 report.

Meanwhile, engine-maker Pratt & Whitney added its own suggestion that the F-35 Joint Program Office decide quickly how it wants to meet the fighter’s rapidly-growing power and cooling needs, so the company can adjust its planned Engine Core Upgrade to better mesh with those requirements.

The Pentagon has previously declined GAO’s suggestion to break out the engine upgrade element of the F-35 program as a separate undertaking, which is why the GAO is now urging Congress to direct the change.

Cost increases and problems with the F-35 airframe and engine tend to be masked under the current arrangement, GAO said, and the magnitude of those cost overruns and schedule issues, if judged separately, could incur Nunn-McCurdy breaches—under the Nunn-McCurdy law of 1982, if a program has cost increases beyond certain benchmarks, it receives added scrutiny or may be automatically canceled.

Other GAO recommendations related to the F-35’s engine include defining long-term requirements for the powerplant.

The GAO agreed with the F-35 Joint Program Office’s business case analysis that found Pratt & Whitney’s ECU is a better and less risky approach to the F-35’s power needs than integrating a new engine from the Air Force’s Adaptive Engine Transition Program (AETP), mainly because of the uncertainty and higher integration cost of a new engine. The AETP engines—GE Aerospace’s XA100 and Pratt’s XA101—also cannot fit the short takeoff/vertical landing F-35B or carrier-landing version F-35C without extensive extra development, the GAO found.

Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall has said the difficulty of integrating an AETP engine with those models was the principal reason the service—in concert with Pentagon leadership–dropped plans for the new engine, although cost was also a big factor.

“You can’t do everything you want to do,” Kendall told the Senate Armed Services Committee in April.

Pratt’s F135 director Jennifer Latka said on a May 31 call with reporters that the company feels the GAO report “validates the Department’s decision to pursue the Engine Core Upgrade on the existing F135.”

But while the GAO report noted the F-35 office has completed the business case regarding a new engine, it also pointed out the Pentagon “has not fully defined the power and cooling requirements the engine and related components will need to support” Block 4 capabilities through 2035.

Specifically, the Joint Program Office has yet to fully assess the cost and technical risks of different engine upgrade and thermal management options, the report stated.

Pratt would like the Pentagon to complete that work, Latka said, so it can determine how it wants to meet the F-35’s increased needs from its Power and Thermal Management System (PTMS), which provides cooling for avionics, radar, and other equipment, as well as emergency power, cockpit conditioning, some electrical power, and more.

Pratt officials have long argued the existing PTMS and engine can provide enough cooling for the F-35’s systems, but doing so requires more heat and stress on the engine, increasing maintenance and cost. Now, Latka said, it would be best from a design and development perspective for the F-35 Joint Program Office to decide its PTMS needs soon so they can be aligned with the Engine Core Upgrade.

For its part, the GAO report states that the current PTMS is already inadequate to meet the F-35’s cooling needs, and the planned Block 4 upgrade will place a heavier burden on the system. Running the engine hotter to produce more cooling is “reducing the life of the engine,” according to the report.

This problem was known back in 2013, and Lockheed wanted to change the F135’s design then to yield more air pressure from the PTMS, “but program officials determined it was too late to redesign the engine given the cost and schedule effects” of doing so, the GAO reported.

“Program officials decided to continue with the F135 engine’s original design with the understanding that there would be increased wear and tear, more maintenance, and reduced life on the engine because it would need to provide more air pressure to the PTMS than its design intended” the audit agency said.

“The misalignment of requirements with the engine and PTMS illustrates why it is important to fully understand the proposed designs at the beginning of an acquisition, prior to committing to development,” the GAO observed.

The GAO is projecting the F-35’s current cooling system won’t be able to meet the fighter’s future needs beyond 2029, particularly those planned for Block 4. Latka argued that is not exactly true but agreed the increased cooling will degrade the F135’s service life, requiring replacement or heavy, unplanned maintenance costs.

It’s “more an art than a science” knowing exactly when the Engine Core Upgrade and PTMS, which are separate systems, will become critical needs, Latka said, but she urged the Pentagon to get on with both efforts as quickly as it can.

“It’s really important to know that [the JPO doesn’t] have a Block 4 plan out to 2035,” Latka said. “They have increments of capabilities that are funded in the next few years that are coming on to the jet, and then they have some more thought-out ideas of what could come on to the jet …and then there are dreams of what we could put on the jet way into the future.”

The F-35’s high sustainment have been a headache for the Pentagon and a source of controversy in Congress for some time now, and the GAO is predicting an extra $38 billion in predicted life-cycle costs. Latka could not say how much of that could be avoided by Pratt’s engine upgrade and a new PTMS.

The GAO report also stated that late engine deliveries are affecting the F-35’s production line, including a chart showing that 97 percent of engines delivered in 2022 were late, up from 46 percent late in 2017.

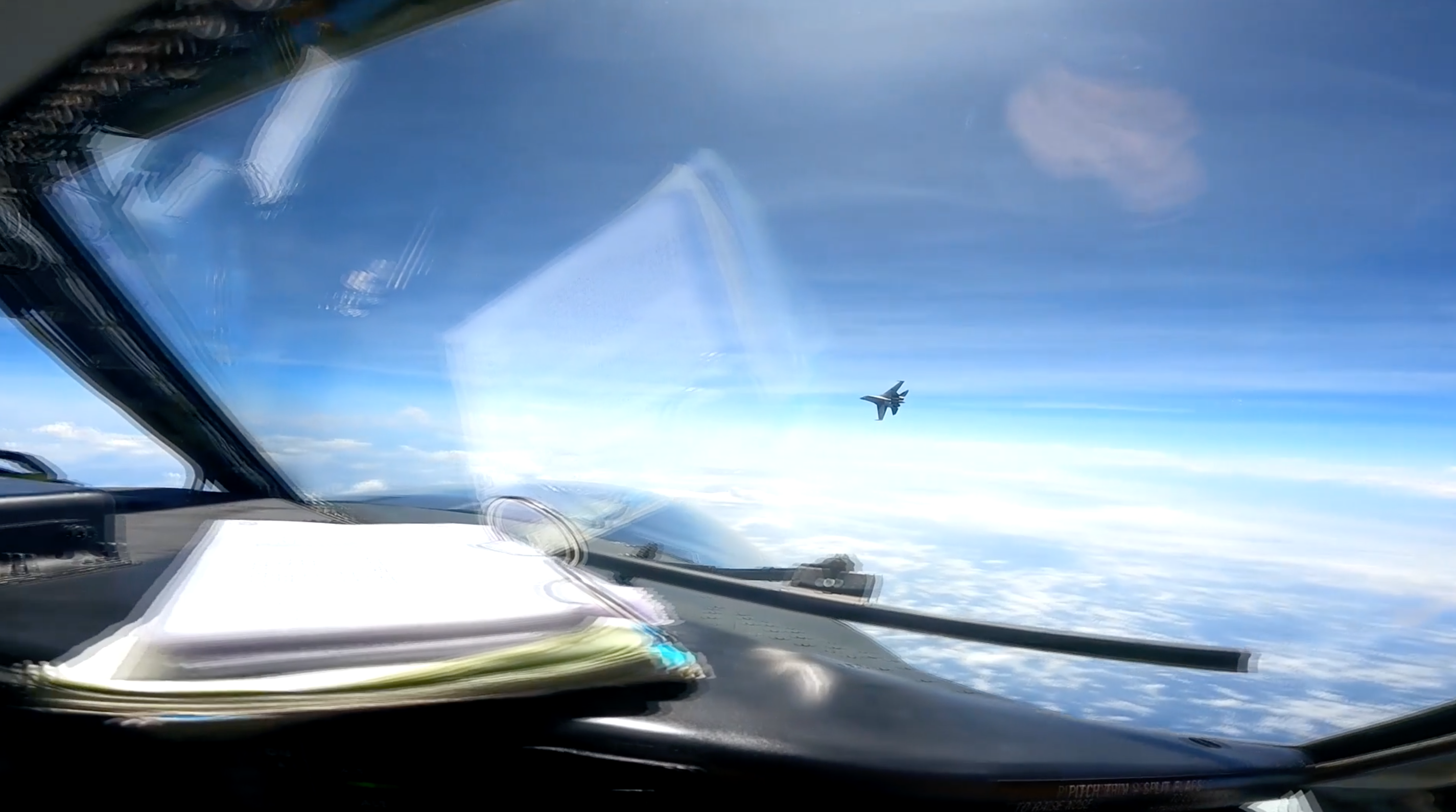

Latka disputed that part of the report, saying it was based on old data. Deliveries of F135 engines and F-35s were paused for several months to investigate a December 2022 crash of an F-35B caused by an engine problem, and during that time, Pratt’s buffer of extra engine waiting at airframe-maker Lockheed Martin shrank. Now, however, it is back to normal, Latka said.

In a statement responding to the GAO report, the JPO said it’s waging a “war on cost” in the F-35 program, that new countries are indicating their confidence in the program by signing up to buy the jet, and that the JPO “looks forward to working with the GAO and program stakeholders” on its recommendations.