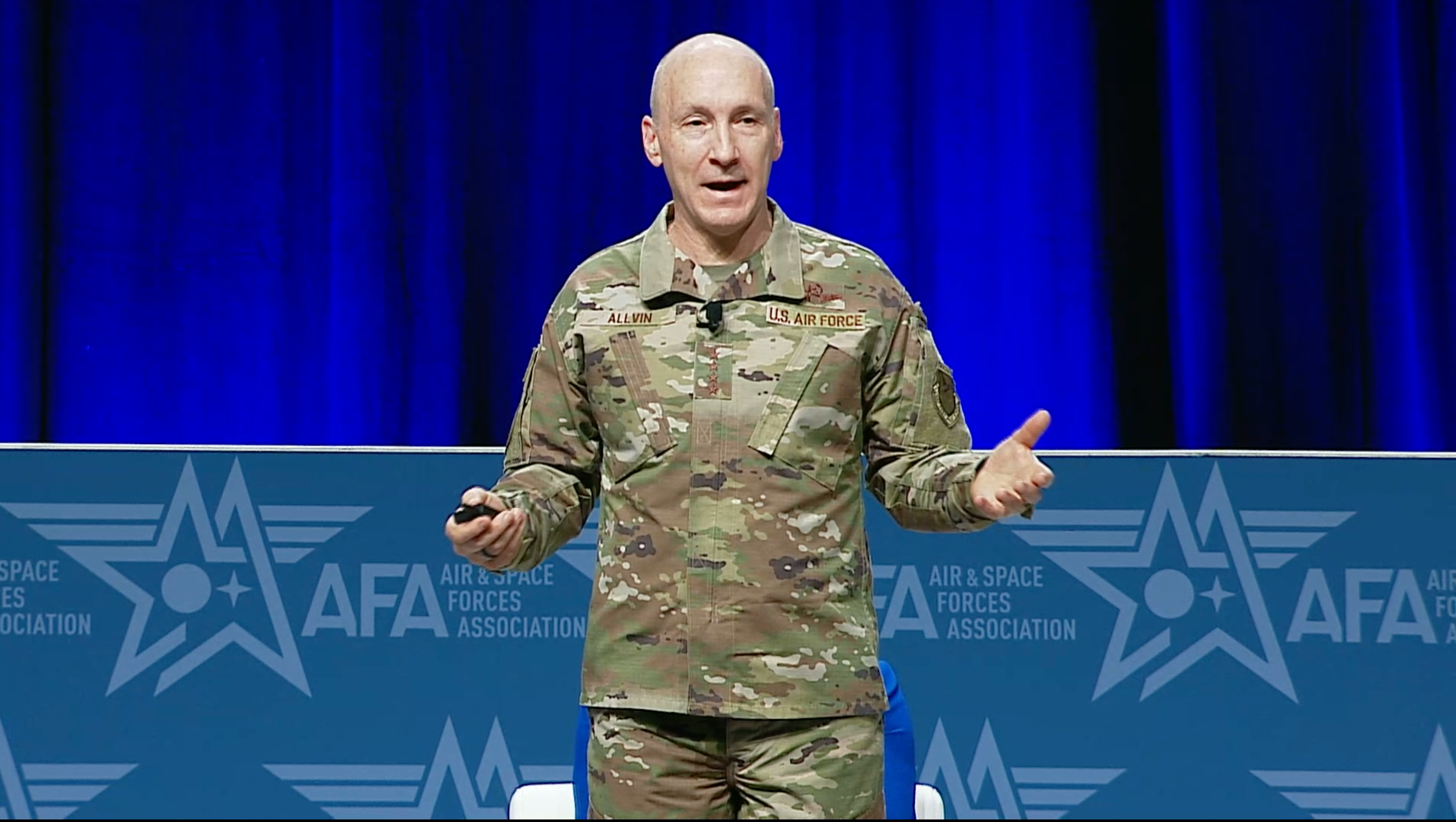

AURORA, Colo.—The Air Force will seek to move away from today’s piecemeal approach to deployments in favor of deploying units that have grown up training together as “units of action,” as part of the department’s ambitious re-optimization for Great Power Competition, Chief of Staff Gen. David W. Allvin said Feb. 12 at the AFA Warfare Symposium.

“Our current paradigm in how we deploy forces often is that we will take one of the mission elements—a fighter squadron or a bomber squadron or a tanker squadron, or what have you, and we’ll take the rest of the forces and sort of crowdsource it from amongst our Air Force, and they will meet in theater,” Allvin said. “That does not work against the pacing challenge. We need to ensure that our combat wings are coherent units of action that have everything they need to be able to execute their wartime tasks.”

Allvin defined three types of wings:

- Deployable combat wings, “where they need to pick up, deploy, employ, generate, and sustain power in theater;”

- In-place combat wings, which generate combat power and fight from their home stations, for which “we need to ensure that where they reside, where they project power from, they have all that they need;”

- Combat generation wings, which “we may not expect to deploy as a wing, but [which] provide combat power that can plug into those combat wings,” Allvin said.

“These wings will prioritize readying whole units that can be combat effective on Day One of a conflict,” an Air Force presentation document stated. “They will train together and, as applicable, deploy and fight together—enhancing their ability to provide direct support to Combatant Commanders.”

Common in all cases is a basic three-tiered structure, including a mission layer, a combat support layer, and a command and control layer.

“The command-and-control layer is the commander and the staff and the ability to plan and execute the wartime tasks,” he said. “The mission layer is the mission generation we’re familiar with—the ops and the maintenance generating that combat power—and then there’s a sustaining layer that ensures that where they are engaged in combat, whether it be in place or deployed, they can sustain with the ability to have the force protection, to do the logistics, to do the intel, all of those things that will enable that to happen.”

Combat wings builds on the “Air Task Force” idea rolled out in September 2023 as a concept for more effectively packaging forces. But as leaders studied the concept, their thinking evolved. The result is more modular, more common across the force, and more intuitive in structure.

“What if the combatant commander wants different combinations of airpower to come and support a particular crisis or conflict?” Allvin asked rhetorically. “So let’s say, for example, we’re going to deploy an F-15E wing, that deployable combat wing needs to be ready to take those forces and deploy forward with all the C2 and all the sustainment. But what if we also would like an F-35 squadron as well? Well, that F-35 squadron should be able to plug into that unit and go. What if we want to use tankers to be able to generate sorties or C-130s to be able to have theater airlift in there? Those mission layers at the squadron layer should be able to plug into this deployable combat wing.”

Combining different kinds of aircraft and missions into a standing operating wing proved too costly when the Air Force tried it in the in the 1990s. Called “composite wings,” these units combined fighters, bombers, and tankers.

Operating a base like that is inefficient. But assembling a wing with those capabilities can be achieved if units are built to be plug-and-play compatible.

“That modularity provides forward flexibility with coherency at home,” Allvin said.

Allvin did not specify a timeline for the creation of the new combat wings. Air Force leaders had planned to test the Air Task Force concept with three units starting in summer 2024, but that effort was suspended, leaving questions about what the forward plan will be.

A key difference between the two is the question of combat service support: “running a main operating base, providing for airfield security, air traffic control, lodging, sustenance, all those types of things at a main operating base,” then-deputy chief of staff for operations, now Vice Chief of Staff Gen. James C. “Jim” Slife said.

Allvin said the relationship between combat wings and base commanders—those responsible for combat service support—will not be permanently joined. Rather, the bases need to be able to keep operating when the wings deploy and when they come under attack, or simply face a natural disaster, whether a flood, a power outage, or a winter storm.

“In this future flight, we cannot expect that there will be a benign environment in the installations that are here after the deploying wing is gone,” Allvin said. “We have to be able to not only fight forward, but understand what it takes to continue to defend and operate the base at home.”