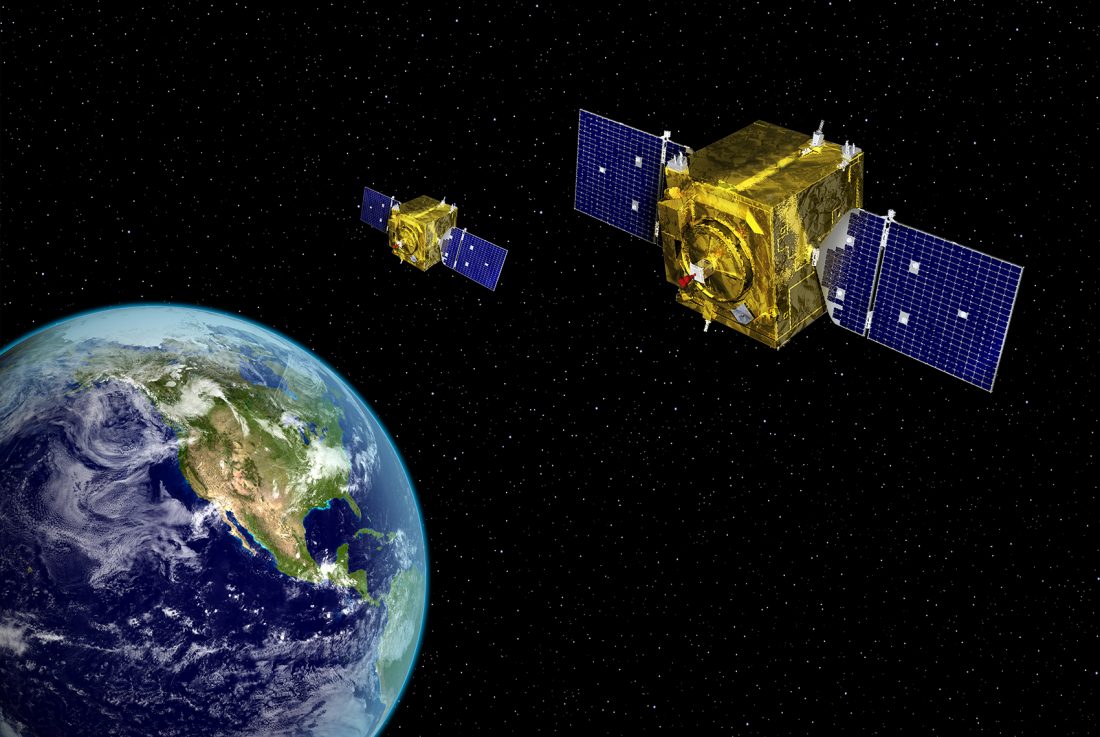

The Space Development Agency awarded contracts Aug. 21 to Northrop Grumman and Lockheed Martin for 36 satellites each as part of Tranche 2 of its Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture (PWSA), a large constellation of satellites in low-Earth orbit.

The two deals, worth a collective $1.55 billion, are part of SDA’s Transport Layer—envisioned as a constellation of up to 500 satellites that will provide constant coverage over 95 percent of the Earth’s surface at all times. The Transport Layer would create a global satellite mesh network, providing high-speed tactical links supporting the Pentagon’s broader plans for Joint All-Domain Command and Control.

Under the deal, Lockheed and Northrop will each build satellites carrying ultra-high-frequency and tactical communications payloads in what SDA is calling the “Beta” segment of Tranche 2. The 36 satellites each contractor is to build will operate in three orbital planes, each with 12 satellites.

Northrop’s agreement is worth $733 million, and Lockheed’s is worth $816. That means the average cost per satellite is about $21.5 million, well above Tournear’s stated goal of $15 million. Whether future tranches will be less costly is still to be seen.

The satellites from this tranche are to be ready for launch by September 2026, according to an SDA release, or 36 months from contract award to launch. That keeps with SDA Director Derek M. Tournear’s stated focus on speed as his top priority, followed by cost and performance.

“We are now solidly in the procurement phase for Tranche 2 of the PWSA to support a 2026 delivery,” Tournear said in a statement. “Tranche 2 brings global persistence for all our capabilities in Tranche 1 and adds advanced tactical data links and future proliferated missions.”

Tranche 1 has yet to be launched—SDA launched its first batch of “Tranche 0” satellites in early April, and a second planned launch has been delayed. SDA plans to start sending Tranche 1 satellites into orbit in the fall of 2024, followed by Tranche 2 in 2026.

Tournear has described Tranche 0 as the “warfighter immersion tranche,” giving service members the opportunity to work with the systems, understand their capabilities, and begin to imagine how they might be employed. Tranche 1 will then operationalize those capabilities, and Tranche 2 will provide global persistence, with the number of satellites in each tranche continuing to grow.

Two more planned segments are planned for the Tranche 2 Transport Layer, Alpha and Gamma. A solicitation for Alpha, which will include 100 satellites, was released in June.

Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture

| TRANCHE | LAYER | # OF SATELLITES | CONTRACTORS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Transport | 20 | York Space Systems, Lockheed Martin |

| Tracking | 8 | SpaceX, L3Harris | |

| 1 | Transport | 126 | York Space Systems, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman |

| Tracking | 35 | L3Harris, Northrop Gumman, Raytheon | |

| Demonstration and Experimentation System | 12 | York Space Systems | |

| 2 | Transport | 72 | Northrop Grumman, Lockheed Martin |

| Transport | 100 | TBA | |

| Transport | 44 (approx.) | TBA | |

| Tracking | 52 (approx.) | TBA | |

| Demonstration and Experimentation System | 20 (approx.) | TBA |

The solicitation for the Beta satellites, issued in late May, noted that SDA anticipated awarding three contracts. An SDA official told Air & Space Forces Magazine that six proposals were received from industry.

“SDA anticipated a maximum of three awardees resulting in the total procurement of six operational planes of T2TL-Beta Space Vehicles,” a spokesman said. “The solicitation tasked each offeror to propose an option for 36 satellites total in addition to the base of 24 satellites. Based on the government’s assessment of best value, SDA made awards to two vendors for 36 satellites for three planes each.”

Tournear has said SDA’s strategy of spreading out contracts among multiple vendors reduces the riks of vendor lock, allowing many different contractors multiple opportunities to bid on opportunities for the PWSA. Thus far, the agency has awarded contracts to:

- York Space Systems

- SpaceX

- L3Harris

- Lockheed Martin

- Northrop Grumman

- Raytheon