Today’s armament maintainers are tasked with performing flightline (O-Level) maintenance with an assortment of legacy test sets that greatly limit the ability to quickly and efficiently verify armament system readiness, diagnose failures, and ultimately return the aircraft to full mission capable (FMC) status. Legacy test sets are typically utilized on only a single aircraft, or perform a single function supporting multiple aircraft, resulting in increased training and logistics challenges, and longer than necessary test and repair times. This not only impacts armament maintainer effectiveness, but limits the realization of Agile Combat Employment (ACE) and the development of Mission-Ready Airmen.

The need for a universal armament test solution, one that is easy to use, portable and rugged, with rapid test and setup times, and common across all platforms and weapons, has become readily apparent and increasingly in demand on the flightline. Working closely with armament maintainers from across the globe, both DOD and ally, Marvin Test Solutions (MTS) identified key functionality and capabilities essential to supporting legacy, current, and future generation platforms and weapons systems. The outcome of this effort resulted in the widely deployed and combat proven MTS-3060A SmartCan™ Universal Armament Test Set. It has become the universal solution for eliminating the burden of multiple, aircraft-specific test sets on the flightline—delivering a standard.

A typical SmartCan kit, with all associated cables and adaptors contained in a single carry case, can replace the flightline test capabilities of over a dozen test sets across USAF fighters and UASs. It can also support a broader implementation to include bombers and surface-to-air defensive systems as needed. See Table 1 for additional details.

All fielded aircraft, manned and unmanned, rotary and fixed wing, can be loaded onto a single SmartCan, eliminating the traditional deployment model of using multiple aircraft-specific armament test sets on the flightline. Test results and measurement variances for each weapon are displayed real-time for review, analysis, and fault-isolation. Additionally, test log files can easily be moved or copied for printing and analysis, supporting emerging predictive maintenance initiatives.

Unlike legacy handheld test sets that are only capable of performing stray voltage and continuity tests, the SmartCan implements functional/active MIL-STD-1760 testing to ensure armament systems are ready to support Smart weapons, before they are loaded. Coupled with munitions communication channels supporting all existing weapons protocols, it provides a full system test for all legacy and Smart weapons. It performs both pre-load and functional checkouts, the testing of multiple squib signals, and implements a cross-fire test process superior to all other O-Level armament test sets in service today.

In addition, SmartCan supports a 4-year calibration cycle dramatically reducing sustainment burdens. This feature, combined with flexible software updates and multi-weapon capabilities, ensures continued relevance for future-generation platforms and munitions.

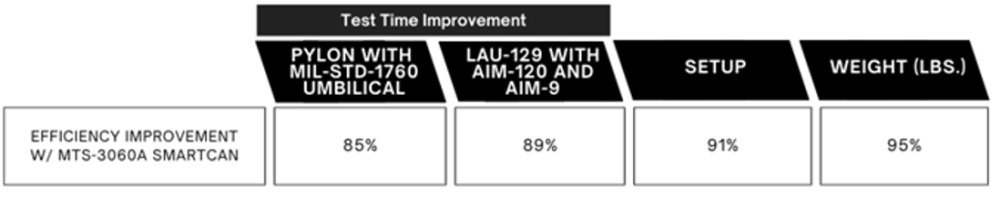

The rugged design, ergonomic layout, and small footprint enables field operation anywhere in the world, making it the ultimate tool for flightline armament test. It is designed and qualified to operate under extreme environmental conditions, meeting MIL-PRF-28800F Class 1, MIL-STD-810C and MIL-STD-461F requirements. Battery operation further enhances field usability; any AA batteries and an innovative power management system enable over 40 hours of test time without the need to replace the batteries. Test setup and execution times are also significantly improved, and the results are striking! F-16 setup times are reduced by an impressive 91% decrease. Similarly, test execution times for a pylon utilizing MIL-STD-1760 and a LAU-129, tested for both AIM-120 and AIM-9X, saw substantial reductions of 85%, and an 89% reduction respectively. See Table 2 for additional details.

Advanced cybersecurity features and protections further differentiate the SmartCan, making this the most cyber-secure O-Level armament test set. Data encryption, a custom operating system, NIST Certified software for Test Program Set (TPS) development, and a removable secure data (SD) card all contribute to the enhanced cybersecurity of this test set. Its design ensures no sensitive data remains on the unit when the card is removed, meeting stringent DOD information assurance standards.

The ability to streamline TPS development and release cycles is another unique advantage of the SmartCan. ATEasy™ and SmartCanEasy create a powerful integrated TPS development environment.

Deployed on 14 platforms, in 21 countries, the SmartCan has also been endorsed by Lockheed Martin and the USAF F-16 System Program Office with SERD #75A77 and granted cybersecurity authority to operate (ATO). Additionally, it was successfully evaluated during AFWERX’s Agile Combat Employment CASE initiative. Its performance continues to demonstrate unmatched versatility, cyber resilience, and operational efficiency across allied forces worldwide

The MTS-3060A SmartCan is the premier O-Level armament test solution currently globally deployed on 14 platforms, in 21 countries, in Systems Integration Labs, with SERD Certification (#75A77) and cybersecurity authority to operate (ATO).

SmartCan is the most advanced O-Level armament test set available, capable of testing all Alternate Mission Equipment (AME) and Aircraft Armament Equipment (AAE) including pylons, launchers, bomb racks, guns, and pods. It delivers: the quickest setup and execution times with reduced training needs, a small logistics footprint, enhanced cybersecurity, and superior active armament test capabilities—all designed to maximize warfighter readiness and combat effectiveness.