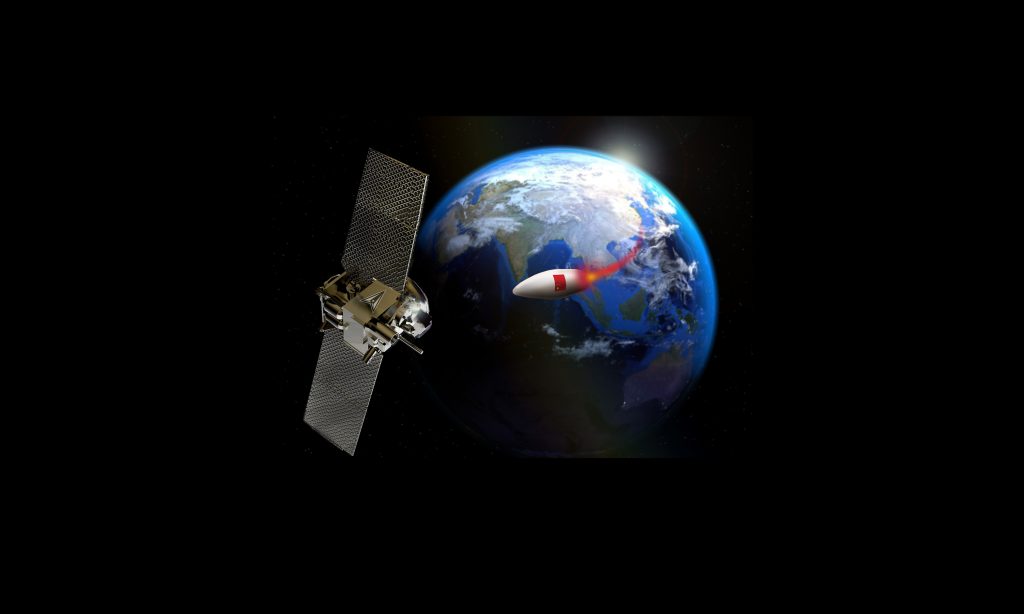

As the Pentagon weighs shifting billions of dollars in funding, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth said the Trump administration plans to step up spending on offensive and defense space operations.

“I feel like there’s no way to ignore the fact that the next and the most important domain of warfare will be the space domain,” Hegseth told senior leaders from the Air Force and Space Force on March 19.

“So, you’re going to see far more investment from this administration into that domain, both offensively and defensively … because that’s where we can continue to maintain an advantage,” Hegseth added.

Hegseth has ordered the services to identify 8 percent in budget “offsets” so funds can be reallocated to the new administration’s priorities. One of those priorities is the Golden Dome missile defense initiative, which could very well lead to more money being invested in the Space Force.

Air Force leaders have also touted the service’s importance, including its role in homeland defense. That message appeared to resonate with the new defense chief.

Hegseth said that the Air Force and Space Force will determine whether the American people live in a century “dominated by the U.S. or dominated by the Chinese.”

“It’s our airpower, the next generation of it, and our ability to project it that will be the decisive factor in whether or not we truly deter our peer [adversaries] of the 21st century,” said Hegseth, who stressed that the “Air Force will be a huge part” of the Trump administration’s military spending plans.

The event was first disclosed in a post by Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. David W. Allvin on the social media site X.

Hegeth’s remarks were reported in an article distributed by the Department of Defense. No reporters were present, and a spokesperson for the Office of the Secretary of Defense declined to offer additional details.

Hegseth said wargames have proved that spacepower is decisive, if sometimes underappreciated.

“There are strategic things that can be done that change the entire [warfighting] calculus that no one else is paying attention to, and I would anticipate that [the space domain] is one of those for us,” he said.

Speaking during a recent Defense One event, both Allvin and Chief of Space Operations Gen. B. Chance Saltzman endorsed the administration’s priorities, including reducing bureaucracy within the Pentagon.

“If you have multiple parts of your Air Force doing the same thing, that’s bureaucracy,” said Allvin. “And when we extract that part out of it to have this Integrated Capability Command that lets them focus on warfighting, now we can sort of revive the warrior ethos and reestablish deterrence by having clear responsibilities for each of the major commands.”

Added Saltzman: “I think in the end, what you’ll see is that because our priorities were so focused on warfighting, so focused on the new emerging threats that everybody is kind of coming to the realization that we have to address, that we were pretty well aligned. We were pretty well aligned with the new administration’s priorities. And so I think the Space Force is going to be in a good spot.”