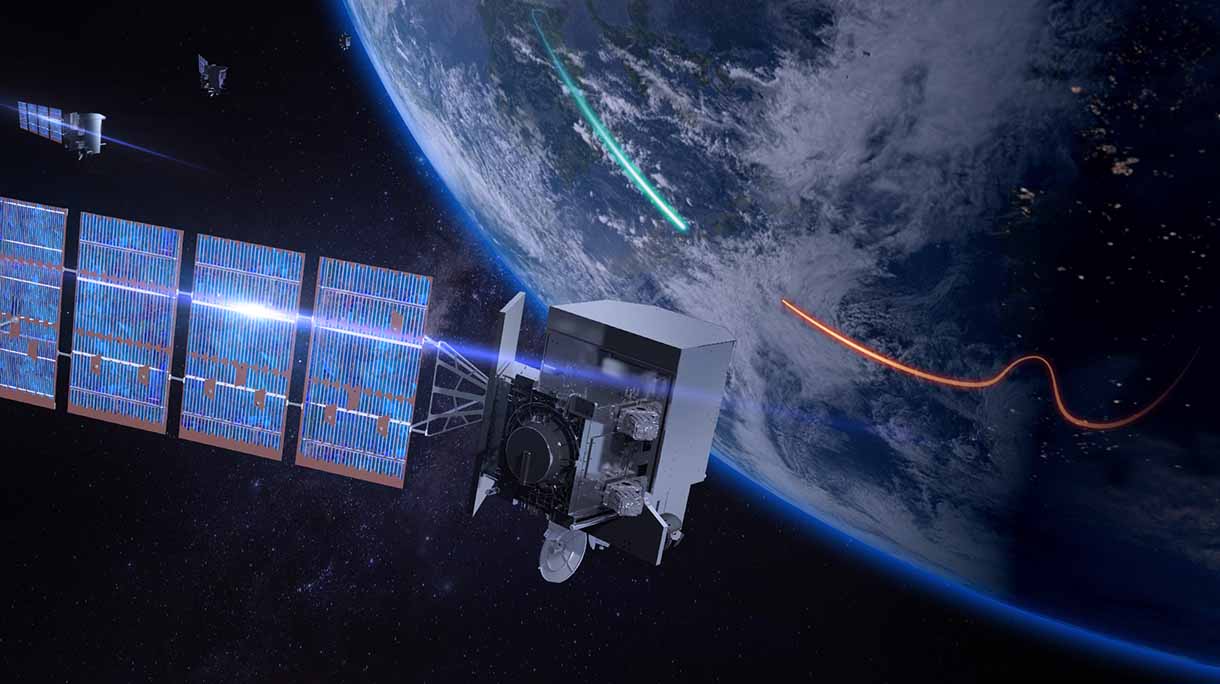

The Air Force is suspending work on a significant part of its new Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile program, ordering a pause on the design and construction of launch facilities being developed by Northrop Grumman.

The suspension comes as the service is working on a plan to restructure the program following significant cost and schedule overruns that triggered a review and required certification from the Secretary of Defense to continue.

“Due to evolving launch facility (LF) requirements in the Command & Launch segment, the Air Force directed the Northrop Grumman Corporation (NGC) to suspend the design, testing, and construction work related to the Command & Launch Segment” of Sentinel, an Air Force spokesperson told Air & Space Forces Magazine.

The order to halt work covers the “LF Standard Design,” which is the baseline design for all planned operational Sentinel launch facilities. The directive also covers work on several sites used for testing, evaluation, and training, the spokesperson said.

The Air Force gave no hint on when the suspension might be lifted.

“The Air Force’s ICBM Systems Directorate is assessing aspects of the current development effort that may be paused, or halted, as the Air Force restructures the program and updates the acquisition strategy,” the spokesperson added.

The sites covered by the order include Launch Facility-26 at Vandenberg Space Force Base, Calif., a test and training facility. Work was also suspended at a former Peacekeeper launch facility at Hill Air Force Base, Utah, and at the Physical Security Systems Test Facility (PSSTF) at Dugway, Utah, a military test site. Also paused is work on launch facility “derivative training devices,” which include maintenance and security forces training facilities at each of the Air Force’s missile wings.

The ICBM Systems Directorate officially stood up last year to help manage the mammoth task of fielding Sentinel as a one-for-one replacement for the 400 currently deployed Minuteman III missiles, which still must be sustained, maintained, and tested. The Air Force has ICBM wings at F.E. Warren Air Force Base, Wyo.; Malmstrom Air Force Base, Mont.; and Minot Air Force Base, N.D. Missile fields are spread out over five states—Colorado, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, and Wyoming.

Northrop Grumman CEO Kathy Warden first indicated there would be a pause on a Jan. 30 earnings call. The Air Force directive was first reported by Defense One.

“We are working with the government on the restructure, but in the meantime, we are performing and meeting important milestones on the [engineering and manufacturing development] contract,” Warden said last month. “The government has said that they project the restructure to take 18 to 24 months, and we’re still very much in that window—though they have paused work on some small infrastructure efforts in the command and launch segment.”

Sentinel, which Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, like his predecessors, has said is a priority for the Department of Defense, is now estimated to cost nearly $141 billion, according to the Pentagon. That triggered a review of the program under the Nunn-McCurdy Act, as the cost was some 81 percent higher than estimated in 2020. That cost overrun also led the DOD to rescind Sentinel’s “Milestone B” approval to enter the engineering and manufacturing development phase, and officials said last year the program could be delayed by several years.

Full operational capability for Sentinel had been set for 2036, and the Pentagon has long argued that the program is vital to maintain the land-based leg of the nuclear triad.

The cost and schedule growth of Sentinel stems mainly from the infrastructure to command and launch the new ICBM and not the missile itself.

“It’s not pulling the plug, but they’re certainly recognizing here that the entire core infrastructure of this system isn’t going to work. It’s going to be assessed,” said Hans Kristensen, director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists.

Air Force and defense officials have said the missile is on track, but the infrastructure would be a significant civil engineering effort.

“I think the part that’s probably missed or lost is the scope and scale,” deputy commander of Air Force Global Strike Command Lt. Gen. Michael J. Lutton told Air & Space Forces Magazine during a visit to an unarmed Minuteman III test at Vandenberg Space Force Base, Calif., last November. “When you look at modernizing that infrastructure … it’s close to 500 facilities across an area of about 33,000 square miles, about the size of the state of South Carolina, and that’s going to be intra-netted. There’s an underground command and control network that connects all that across five states. So, when one looks at that, that’s highly complex.”

Air Force officials have said Minuteman III could be in service until 2050. The missile was originally expected to be decommissioned in the 2030s. Pentagon officials have argued the U.S. needs to embark on a costly but overdue modernization of all three legs of its nuclear triad, which also includes fielding the B-21 Raider bomber and Columbia-class submarine.

“You’ll push the program well into the 2030s,” Kristensen said of the latest pause. “They were pushing this single source contract, forging ahead with this, rushing the program. … Now the whole system, ironically, will face exactly that delay.”

The Air Force has hinted changes could be coming to the ground infrastructure before the recent move. In September, then-Air Force acquisition chief Andrew Hunter said the service could “change our design for the ground infrastructure to be simpler, more affordable.” Those comments added to ones made last July, in which Hunter indicated that there were “elements of the ground infrastructure where there may be opportunities for competition”—which could strip work away from Northrop Grumman.

Editor’s Note: This story was updated on Feb. 12 with additional details.