The Space Force expects to finish calibrating and start using its newest weather satellite this fall, the head of Space Systems Command’s space sensing directorate said.

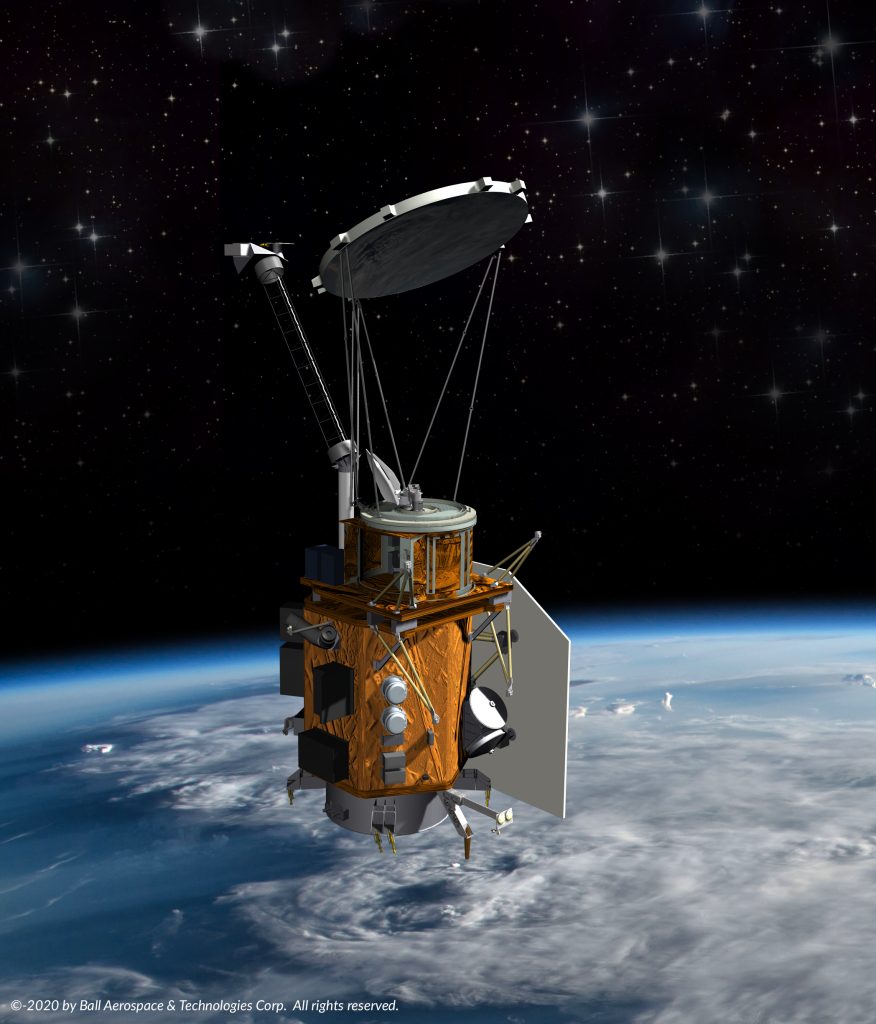

The first Weather System Follow-on—Microwave satellite, built by Ball Aerospace, launched in April and is meant to measure things like ocean surface winds, tropical cyclone intensity, sea ice, soil moisture, and snow depth, as well as low Earth orbit (LEO) energetic charged particles.

The WSF-M launch came just one month after the Space Force launched an Electro-Optical/Infrared (EO/IR) Weather Systems (EWS) cubesat built by Orion Space Systems to demonstrate the technology.

Both programs are meant to replace the aging Defense Meteorological Support Program, which has been in orbit since the 1960s and is scheduled to reach the end of its service life in 2026.

“Both have had great success quickly getting through their checkouts and starting to produce data and getting the calibrations right,” said Space Sensing director Col. Robert Davis, speaking July 25 at a virtual event held by the National Security Space Association.

Davis said more launches are to come for both programs—another EWS satellite, this one built by General Atomics, will launch in 2025, followed by a second WSF-M satellite in 2026 and another EWS satellite after that. General Atomics announced July 11 that it has received a contract to build the second operational demonstration EWS satellite.

“But then we have a question,” Davis said. “What comes after those two disaggregated systems that are replacing DMSP?” Davis sees a future that leverages more weather data from commercial satellite operators.

Weather satellites are used for everything from flight plans to humanitarian and disaster relief operations, and the importance of accurate weather is seen as growing.

The answer likely lies with exploiting civil and commercial technologies and systems, he suggested. SSC launched a market research study earlier this year and held an industry day in May, and while the results are not finalized, Davis offered an optimistic view on how much commercial can help.

“There’s a lot of exploit already happening in this area between civil and international. Other things are out there that we might be able to exploit,” he said. “But really what we’re really focused on for this study is, what can we buy? There’s emerging weather capabilities out there in the commercial market. And so we’re very interested in exploring those to see what kind of requirements can we solve for the nation, for the warfighter, with a different approach that provides resiliency and provides economies of scale and whatnot to build this more efficiently.”

The Space Force has already transferred multiple satellites over from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and Davis said the partnership between the two organizations is “great” and “a close collaboration.”

The question of how much commercial industry can help is not a settled one. The Space Force’s Commercial Space Strategy, released this spring, ranked space-based environmental monitoring as a priority, but fifth on a list of eight mission areas where it believes commercial capabilities exist and it sees a need to integrate them.

Late last year, AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies produced a study arguing that the Space Force should seek help from industry—but should also field its own satellites.

“The value of having assured access to DOD-owned and -operated SBEM capabilities cannot be overstated,” wrote the study’s authors, Douglas A. Birkey and Charles Galbreath. “The warfighter cannot risk a commercial provider imposing policies or politics that limit how their systems might be used in combat or whether they can be used in a particular conflict.”

In another study, a 2023 policy paper by two other Mitchell fellows, Tim Ryan and Scott Brodeu argued that commercial weather satellite data “is not a substitute for a DMSP replacement system, nor does it provide the necessary organic SBEM capabilities DOD requires.”

Davis agreed that Pentagon-owned systems have great value, but also said commercial capabilities can be adapted to answer the Space Force’s requirements.

“We completely recognize that it might not be a perfect fit based on what commercial has provided,” Davis said. “But we have to make sure we’re asking those tough questions about what can we do with the commercial and move forward and partner with commercial to tailor their offerings to meet our requirements.”