Extending the service life of the Air Force’s B-61-12 nuclear gravity bomb remains on schedule a year after officials acknowledged life-cycle testing of a commercial-grade replacement part would delay the program by 16 to 18 months.

As of now, the first extended-life B-61-12 will be complete in late 2021 or early 2022, rather than this spring as originally planned, said Lisa Gordon-Hagerty, undersecretary of energy for nuclear security at the National Nuclear Security Administration.

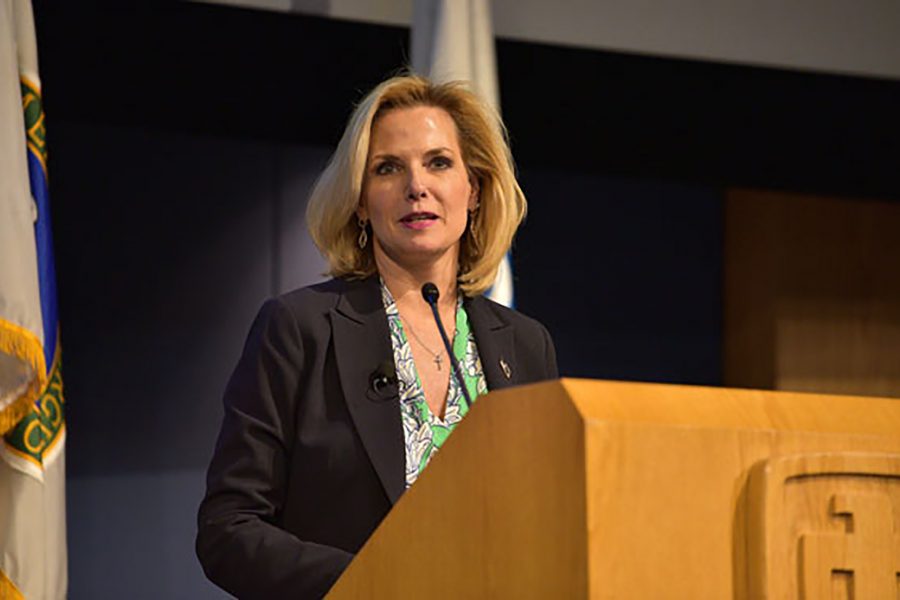

“We have challenges with it, unanticipated, but it’s what we’re planning for the future,” Hagerty told Air Force Magazine, following an AFA Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies event in Washington, D.C., Jan. 16.

Yet the impact on the schedule is not as great as it looks, affecting the first production unit (FPU), but not the timing for when the program concludes.

“The FPU will change, but the final production unit will not,” Gordon-Hagerty said. “That’s our anticipation right now, and we will not ask for any additional resources [for this program] in 2020.”

With weapons designed and built decades ago, some parts are no longer available, requiring substitutes that must be certified to remain effective over a long lifetime. In this case, the part was a capacitor. Life-cycle testing is now ongoing to ensure the part will remain functional as anticipated.

“The new part works well,” Gordon-Hagerty said. “But we don’t want to have to put our hands on a nuclear weapon [to service it]. We want to minimize that. And in order to do so, we need to make sure that every part that goes into that nuclear explosive package will last 30-plus years.”

More parts issues could still crop up. “I won’t be surprised if we have other issues similar to the capacitor issue,” Gordon-Hagerty said. “We’ve taken a hiatus for the last 20 years” on building nuclear weapons while the nation “invested in stockpile stewardship, rather than stockpile management.”

Building New Nuclear ‘Pits’

Nuclear modernization issues can be found in every part of the nuclear triad, and every step in the process, and every part of the supply chain. So much must be modernized over the coming years that the sheer scale of the challenges could be daunting. Indeed, even as she touts the efforts to do so, Gordon-Hagerty warns that even just enabling modernization remains on the horizon.

Actual weapons modernization? “We’re not ready to do that,” Gordon-Hagerty said.

Over the next 10 years, NNSA must rebuild its nuclear infrastructure before it can revamp its weapons. “We are waking up our system,” she says. For example, the nation’s production capacity for nuclear pits—the core of a nuclear bomb—was just five in 2019, and that was a major accomplishment. The goal is to produce 80 pits in 2030.

To produce 80 pits per year, Gordon-Hagerty said NNSA is overhauling two sites, to minimize the risk that one plant becomes incapacitated for any reason. Production will be split unevenly between the Los Alamos Plutonium Facility-4 and the former Savannah River MOX fuel fabrication site, which she said “will be repurposed” as the Savannah River Plutonium Processing Facility.

“We have a lot of challenges ahead of us, but in 2026, we will, by God, make that 30 pits per year at Los Alamos, and we will hit not less than 50 pits per year in 2030 at the Savannah River site,” Gordon-Hagerty said, her voice rising for emphasis. “That’s our goal, and it’s attainable. … We know what we’re doing.”