The next Advanced Battle Management System experiment will focus on the U.S. Space Force, and the one after that will be a deployed event in U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, Air Force Chief Architect Preston Dunlap said May 7.

The next ABMS experiment will be “an expanded version” of the one that was supposed to have taken place in April, Dunlap said during an AFA Mitchell Institute virtual event. The ABMS experimentation schedule is supposed to take place in four-month increments; the last one took place in December 2019, and was focused on U.S. Northern Command. The April iteration was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the next will run in “late August, early September,” Dunlap said.

“There’s going to be a variety of adjustments,” he said of the next event. Gen. Jay Raymond, head of U.S. Space Force, will be the “supported” commander, Dunlap said. U.S. Northern Command will again be involved, “keeping custody” of inbound cruise missiles and orchestrating a range of sensors and shooters in the air, on the surface, and in the water. U.S. Strategic Command also will play a role in the exercise.

The event will “integrate more of the kill chain/kill web,” Dunlap said. “More sensors, more live fires happening in each of the domains.” As a practical matter, the on-ramp will focus on “driving out some of the integration risk” identified in the previous iteration, and adding in “more advanced software.”

The follow-on event, slated for this coming December, will be focused on INDOPACOM and will happen as a “deployed” event, Dunlap said, with Raymond again serving as a “supported” leader, along with INDOPACOM chief Adm. Philip Davidson.

“It will be exciting to take it out to the theater,” Dunlap said, declining to provide additional details. One of the hallmarks of the experimentation process, he said, is to present commanders with an unexpected situation that requires their teams to improvise and use new capabilities without a certain set-piece outcome.

In the past, such exercises might have taken place on a two-year cycle, Dunlap said, with “a nice drum beat,” but “we don’t want to create fixed kill chains where we can bubble-gum and duct-tape things together. We want to reflect what might really happen in a conflict, which is uncertainty.” He said the exercise team won’t know exactly what the combatant commander will ask for, so “we are designing in the ability to be flexible and agile, both within that four-month period but also within subsequent four-month periods into the future.”

For the COVID-19 crisis, Dunlap said the Air Force has distributed laptops or personal electronic devices to servicemembers that allow them to access top-secret data, but the encryption is purely software-based and the device is not a “secure” device when not involved with classified information. The project is called deviceONE, and was developed by the Air Force Research Laboratory.

The team “pulled together very rapidly to do something we were going to demonstrate in April as a prototype,” Dunlap said.

The laptops have “the ability to process classified information on a device that’s unclassified when you’re not using it,” he explained. “So you could literally throw it in the street, no problem, [though] I wouldn’t recommend it.” The software is called SecureView.

“We’re deploying about 1,000 of these,” he said. The devices assisted with COVID response in New York City and aboard the Navy hospital ship Comfort. The deviceONE deployment is an example of an “on-ramp” producing real-world, tangible results of the ABMS investments, he said.

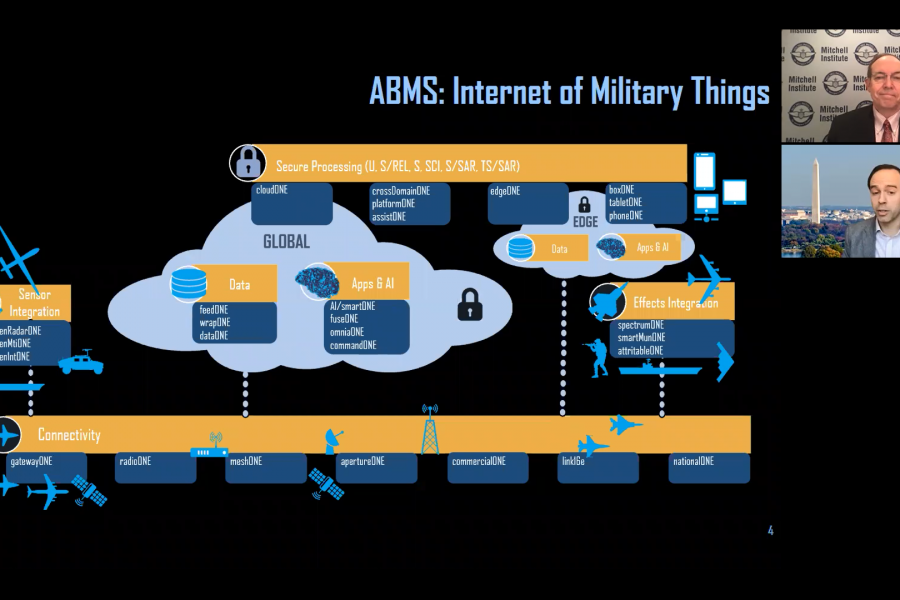

Asked how the Air Force is persuading Congress to support ABMS when it’s a network instead of a tangible thing that clearly supports constituencies, Dunlap said Congress understands “there’s the operational imperative. You have to work together.” He’s been able to show that when, for example, a fighter is “ABMS’d,” its usefulness “increases exponentially.”

It’s obvious, he said, that “no single platform, however awesome, will be able to get the [whole] job done.”

While decision-makers “may not be able to ‘see’ the network … they ought to be able to see the platforms in their areas, their bases, take on power they never had before,” he said.

Dunlap also said the ABMS program is deliberately being kept broad and experimental to prevent it from falling into timeworn traps that would kill its connectivity.

“If you relegate this to a program element … inside of a platform, you will always have that connectivity line be the first thing to go,” he said. “Program managers are trained: Don’t ever make your project dependent on somebody else, … we’ve seen this time and time again. … You build one part, but the connectivity never happens. And so, you’ve got to be able to do it this way.”