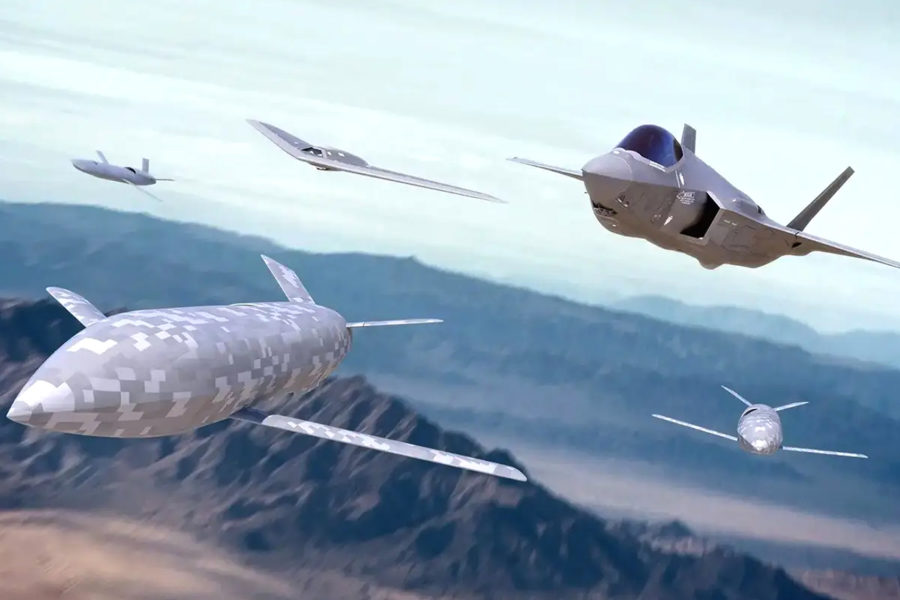

The Air Force should build its capacity and striking power with collaborative combat aircraft but must put the teaming aspect of the new class of weapons first, getting the concepts and software right at the outset to ensure that autonomous airplanes do what’s needed and expected—and can be trusted—a new paper argues.

“The Air Force is not putting sufficient priority on the teaming aspects” of CCAs, said Heather R. Penney of the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, author of the new paper “Five Imperatives for Developing Collaborative Combat Aircraft for Teaming Operations.” She told reporters at a preview of the paper that the service is rushing to develop autonomous aircraft technology without an adequate focus on how, specifically, they’ll be used.

The Air Force’s technology enterprise and the defense industry have been preoccupied with “how … you take the human out of the cockpit,” she said, solving problems such as navigation, terrain avoidance, sensor and weapons management, etc.—“decomposing the mission threads into all the tasks” in a fighter mission.

While that’s important, “What’s being neglected is how CCAs are going to team with humans … How do they engage with humans in the battlespace; how do they fly with humans, handle changing scenarios?” she said. That interaction is “critical, because it’s foundational” to making CCAs succeed operationally.

Based on surveys of combat pilots, Penney said they harbor “great skepticism” about whether CCAs can be absorbed into combat formations without creating new problems that will make the fight more difficult. Pilots must be convinced that CCAs will provide a combat benefit, and that can only be accomplished by involving pilots in the development of tactics, techniques, and procedures written into CCA control laws and software.

She acknowledged, however, that the Air Force is short of pilots—particularly pilots of fifth-generation fighters—who could be spared to help develop tactics, techniques, and procedures for CCAs. While the industry is hiring some reservists and former fourth-generation fighter pilots to help in this regard, they may not be fully up to speed on the modern air war.

Still, “a fourth-gen pilot is better than none,” she said. Engineers alone cannot and should not have to guess how to build an easy-to-use, valuable interface for pilots and CCAs.

Penney argued that the Air Force is right to purse CCAs because they offer many advantages and solutions to tough Air Force problems. They address USAF’s need for a quick operating tempo, the ability to mount attacks in mass, “attrition tolerance,” the ability to have a strategic reserve, and operational resilience, and they create operational complexity for the enemy, she said.

Unlike crewed aircraft, if a CCA is shot down, no pilot is lost, and an inexpensive replacement aircraft can be fielded by the same people with no loss of skill. Given that USAF already faces a chronic pilot shortage, this is a major plus, Penney said.

The CCAs must also be autonomous, because relying on remotely piloted aircraft demands numbers of pilots USAF can’t generate.

“A one-to-one ratio” between pilots and CCAs “is not going to meet the needs of what we have to do for the future,” Penney said.

Autonomous aircraft “that outnumber humans in the battlespace” are becoming possible because “the miniaturization … the speed of processing, the advanced software techniques, and the advent of machine learning/deep neural networks, artificial intelligence, and datalinks” have all matured at the same time, she said.

But the ability to adapt to changing conditions and new instructions on the fly will be the discriminator as to whether CCAs really work, she said. Those capabilities must be built in from the start; they cannot be “bolted on afterward.” The software must take a DevSecOps approach and be ready before the CCAs are fielded, Penney argued.

If they’re not, “we won’t get this right,” she said.

Penney also said pilots need to understand how the artificial intelligence in CCAs will behave, so the autonomous aircraft can be trusted. Aircrews must also not be unduly burdened by the task of managing CCAs “without them becoming task saturated.” The preferred approach now—and “the direction industry is leaning in”—is to direct CCAs by voice, Penney said. But that “may or may not be the best way” for pilots to coordinate with the unscrewed aircraft, she said. Multiple means of control may be needed to provide redundancy. It may turn out that the direction is issued in part “by someone on a workstation aboard an E-7” or similar command and control aircraft.

“It’s important that we not split leadership” of combat formations, she said. “But that is something that will only be discovered through experimentation, and with actual flights with actual crews.”

Gen. Mark D. Kelly, head of Air Combat Command, told reporters at AFA’s Air, Space & Cyber Conference in September that USAF must put the new CCA technology into the hands of the pilots to wring them out and find out what works and what doesn’t, in a rapid series of exercises and iterations. Otherwise, USAF is headed for an “exquisite” failure with CCAs which will require the service to, at great cost, “start over.”

Penney recommended that USAF observe five imperatives for CCA development:

- Figure out the best mix of human-CCA teams “based on each teammate’s strengths.” That means leaving humans to apply initiative, experience, and creativity and relying on the machines to do brute-force calculations and other mechanical functions at which they are better than people.

- Include operators in CCA development and make sure pilots understand how CCA control laws work, just as they understand how their missiles and other weapons work.

- Ensure that warfighters can trust and depend on CCA autonomy.

- Ensure that humans can maintain “assured control” over what CCAs do “in highly dynamic operations.”

- Ensure that teaming workloads are manageable for the humans.

Penney noted that USAF plans to retire some 500 or so crewed combat aircraft in the coming years, using some of the savings to develop CCAs.

“The Air Force is making big bets on unproven technology” with CCAs, Penney said. And while the new aircraft will go a long way toward fixing USAF’s capacity shortfalls, it’s “an irreversible decision,” so the service “has to get this right.”