Combatting sexual assault and harassment in the ranks presents a “huge problem” for the National Guard, a top lawmaker on the House Armed Services Committee warned Jan. 19.

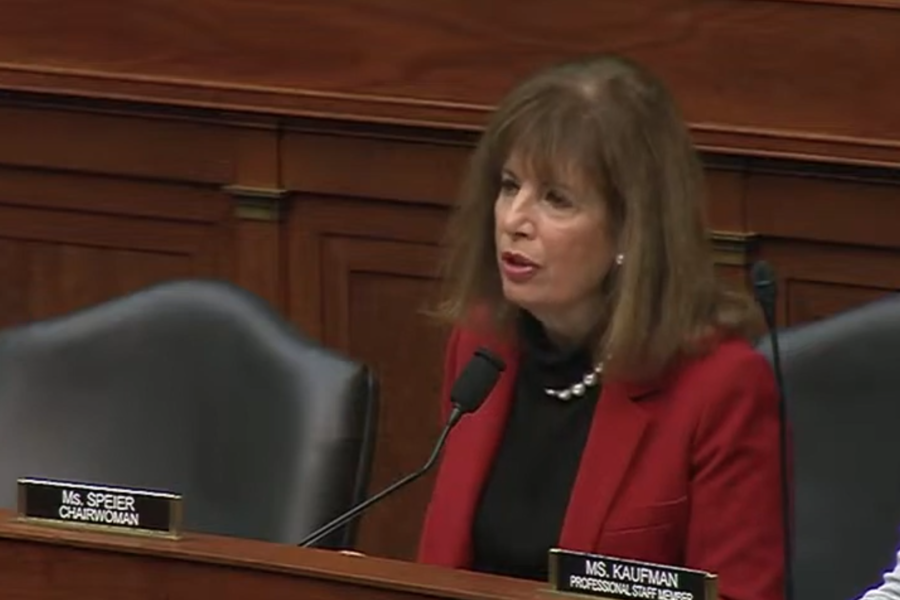

Questioning National Guard Bureau Chief Gen. Daniel R. Hokanson during a military personnel subcommittee hearing on the topic, Rep. Jackie Speier (D-Calif.), chair of the panel, added that she had “some serious concerns” over the Guard’s ability to protect Airmen and Soldiers from harassment and assault if state officials fail to do so.

At the heart of Speier’s concerns is the process by which the Guard investigates allegations of assault and harassment. Any allegations are first referred to local law enforcement, Hokanson told lawmakers. Then, if the local authorities decline to pursue the case, the state’s adjutant general can request that the Bureau’s Office of Complex Investigations conduct an investigation.

The OCI, however, is “not a criminal investigative organization,” Brig. Gen. Charles M. Walker, director of the office, told the subcommittee. “We provide administrative investigations as a backstop so the victims and the National Guard will have an opportunity to address sexual violence against its members and to remove those within our ranks who may be perpetrators, in administrative contexts.”

OCI investigations are also complicated by the fact that different states have different military laws outside the Uniform Code of Military Justice, creating a web of different standards to consider.

“Because there are changes to the Uniform Code of Military Justice, each of the states that have a state code of military justice may or may not make changes as quickly as those adjust,” Hokanson said. “And so we really rely on our OCI as they go out to investigate to really look at the State Code of Military Justice and how it applies.”

What troubled Speier most, though, was the power adjutant generals hold over the investigative process.

“In many respects, what’s going on in the National Guard is what went on in the military, when it was up to the chain of command to make a determination as to whether or not to pursue a sexual assault case,” Speier said. “And we found out that for a number of reasons, they chose not to do that, and [an adjutant general] who has a number of sexual assault cases that occur under their command [may] become loath to report them, or seek assistance of OCI, for fear that it might reflect poorly on them. And sometimes they are the assaulter.”

The 2022 National Defense Authorization Act included an update of the UCMJ, taking the decision to prosecute certain crimes such as rape, sexual assault, murder, and kidnapping from the chain of command. The bill follows up on the Pentagon’s own report from its independent review commission on sexual assault in the military, which included 82 different recommendations.

Implementing these changes and recommendations across the network of 54 different states, territories, and Washington D.C., however, is taking time. Hokanson told lawmakers that more than six months after the IRC issued its recommendations, the National Guard Bureau had yet to implement any, citing a lack of resources.

Still, Hokanson expressed confidence that “I have all the authorities I need to work with the states to make sure that they follow the service guidance.”

Speier was seemingly unconvinced, noting that Hokanson seems to be limited solely to persuading and advocating, not mandating, changes.

“So I’ve got some serious concerns. It’s $26 billion that we [send] out every year to the states. And we have no control, no authority to protect those National Guard service members if the state chooses not to,” Speier said.

While Speier expressed skepticism, the OCI has seen an uptick in investigations, Walker said, in part thanks to additional resources and changes that allowed the office to add more investigators. Hokanson specified that the number of investigators has increased some 60 percent.

“With the renewed and enhanced ability to actually intake cases, we’ve seen a jump in cases particularly this fiscal year,” Walker said. “We’re running definitely ahead of what we had historically in any year already.”

While Walker expressed confidence that his office has enough investigators to handle the increase in cases, multiple lawmakers showed concern about the timeliness, or lack thereof, to those investigations. Hokanson echoed the concern while addressing the backlog of cases, calling extended timelines “really unacceptable.”

But Walker was quick to note that some of the issue of timeliness is outside of OCI’s control.

“Everyone talks of timeliness, but I want us to think about the National Guard and what we’re doing,” Walker said. “We’ve got a force that’s 75 to 80 percent part time. We are a full-time investigative capability, but we also depend on the victim’s counsel, the defense’s counsel, and the state to have the witnesses available when we do an investigation. Oftentimes, we’re limited to drill periods, which happen once a month. So for the National Guard, three days is actually 45 days equivalent, given the availability of our witnesses and the availability of us to get onsite to do investigations.”

Still, Speier, who is slated to retire from Congress in January 2023, indicated that she won’t let the issue drop for the rest of her term.

“To the National Guard: The spotlight of Congress is on you. Take care of your Soldiers. Take care of your Airmen. Stamp out sexual harassment and assault. Stop the retaliation. I am watching,” Speier said.