The looming decision on the future of the F-35’s engine—Pratt & Whitney’s F135—has fostered plenty of debate, with some suggesting the F135 should be completely replaced with a new engine through the Adaptive Engine Transition Program (AETP), while others say integrating a new adaptive engine into the F-35 would be wasteful and unnecessary.

Even Pratt & Whitney—which is developing its own adaptive engine, the XA101, through AETP—insists that the F-35’s continued aerial dominance as a joint strike fighter depends on incremental upgrades to the existing technology powering it.

“Adaptive engines are sixth-gen technology,” said Jen Latka, Vice President of Pratt & Whitney’s F135 program. “That technology is what keeps us at the forefront in terms of the U.S.’s national advantage, so we are very thankful for the adaptive engine program—but while it’s critical to develop sixth-generation propulsion technologies, the AETP engines aren’t optimized for the F-35 program.”

The solution proposed by Pratt & Whitney, a Raytheon Technologies company, is an engine core upgrade (ECU) that can meet DOD imperatives for the F-35 that adaptive engines can’t, particularly maintaining tri-variant commonality—adaptive engines won’t fit in the F-35B and likely won’t be retrofitted into already fielded F-35s, and will not deliver a meaningful quantity of Block 4-enabled F-35s by 2028, when the warfighter needs them.

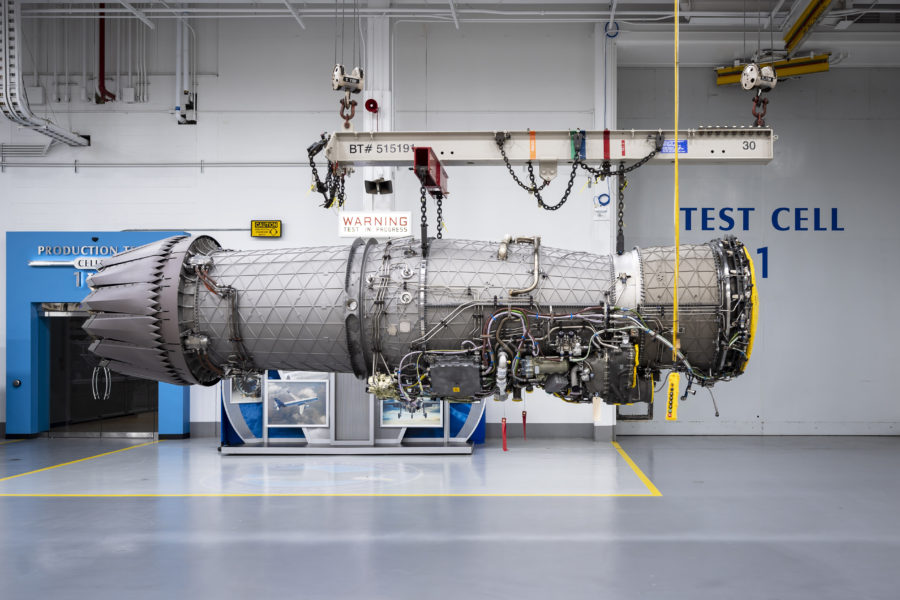

The ECU is a limited scope upgrade—the product looks very similar to the existing motor in the F-35 but incorporates the latest design tools into the same supply base. The upgrade wouldn’t require any of the F-35’s interfaces to change and is limited to what Latka calls “the power module,” which is just the core of the engine.

“What that means is you can come into depot for your regularly-scheduled overhaul with the current configuration and then leave depot with the upgraded core,” Latka said. Because the upgraded engine is retrofittable, the upgrade could be dropped in F-35s in the depot in addition to on the assembly line—greatly accelerating the pace at which Block 4-enabled F-35s will reach the operational fleet.

Pratt & Whitney estimates that the ECU can save the DOD a total of $40 billion over the life of the program, but in near-term savings alone it has a clear advantage over a new engine. Latka reports that development will cost around $2.4 billion for the entire Engineering and Manufacturing Development phase over the five-year Future Years Defense Program (FYDP). That’s just a fraction of the price tag on fully developing an AETP alternative, which Secretary Frank Kendall has said will cost nearly $7 billion and result in reduced procurement volumes.

“In the next five years, there’s billions of dollars that could be saved,” Latka said. “And it’s not only the cost of a new engine—it would be that plus the core upgrade, because the core upgrade will need to be done regardless, to support the international customers and the STOVL variant.”

“And in comparing production costs, the core upgrade remains the financially prudent option. An upgraded F135 would be production cost neutral,” she said, “while the initial cost of a brand-new adaptive engine would be about two and half times that of current the F135 and would add about $4 billion in production costs across the life of the program.”

“We’ve already come down the learning curve and taken out 50 percent of the cost of the engine,” she added. Even accounting for an AETP learning curve, Latka said AETP “would still be more expensive than the current motor because it’s significantly heavier.”

While the savings offered by Pratt & Whitney’s single development program are impressive, they’re marginal compared to lifecycle savings. Sustainment is a crucial piece of the debate over F-35 engines, but its implications extend beyond just the cost. Pratt & Whitney’s solution can potentially save the Pentagon tens of billions of dollars over the F135’s (and the F-35’s) lifecycle because it retains an infrastructure that has already been built and invested in—and when sustainment efforts are disrupted, disruption soon follows.

“With a new adaptive engine, you are going out there and having to create a second infrastructure,” Latka said. “So, you would need all new tooling, all new support equipment, and all new depots. You have to fund two sustaining engineering teams, two configuration management teams … you have two of everything because you’re maintaining two totally different products.”

Bifurcation threatens the interoperability of the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program, which depends on a common engine and global spares pool among American and international F-35 operators. The maintenance, repair, and overhaul (MRO) network devoted to the F135, for instance, already has multiple locations around the globe that will be able to support ECU sustainment as well—with more planned in the future. But F-35As powered by AETP engines wouldn’t be able to utilize that extensive sustainment network and would need to stand up a parallel AETP sustainment network at a significant cost.

“The drive right now has got to be around maximizing interoperability among the partners,” Latka said. “Another issue is whether the adaptive engine is exportable; it’s sixth-gen technology. Perhaps it could be exportable one day, but it doesn’t appear to be right now.”

And with global tensions on the rise, Latka said, there’s a strict timeline on not only improving the F-35’s operating capabilities but also growing the fleet before a potential conflict happens. That’s harder to do while trying to fit brand new, unproven engine technology into an existing jet.

“When we think about the timeline and the pacing threats, cutting tails hurts that fight,” Latka said. “But secondly, we need to field an engine upgrade as fast as we can.”

While adaptive engine technology boasts improved range over the existing F135, Latka said that these enhancements could distract from what really matters to the combatant commanders: getting as many Block 4-enabled jets fielded as quickly as possible. Block 4 quantity and readiness equals relevant capability.

Pratt & Whitney has said its upgraded engine will be ready to enter service by 2028, facilitating SECAF’s readiness imperative while offering performance improvements and significant cost avoidance that allows increased investment in the Secretary’s other operational imperatives. But Latka reiterated that these improvements are ancillary to ensuring operational readiness—it’s quantity and Block 4 capabilities that truly matter, and Pratt & Whitney’s Engine Core Upgrade would deliver both while saving billions of dollars and ensuring commonality across the fleet of F-35s operated by the DOD and allied partners around the globe.