FARNBOROUGH, U.K.—Military and defense industry officials are proud to say the Global Positioning System of satellites has entrenched itself as the world standard of position, navigation, and timing.

But new threats—and some futuristic considerations—are leading some to think bigger than GPS when it comes to the systems that help undergird military operations and daily life.

“We’re at a time when we have the opportunity to expand beyond just that concept of a singular [medium Earth orbit] constellation,” Johnathon Caldwell, vice president and general manager of Lockheed Martin’s military space division, told Air Force Magazine in an exclusive interview at the Farnborough International Airshow. “There are opportunities to put different orbits into play, to provide greater resilience for the civilian applications and the military applications.”

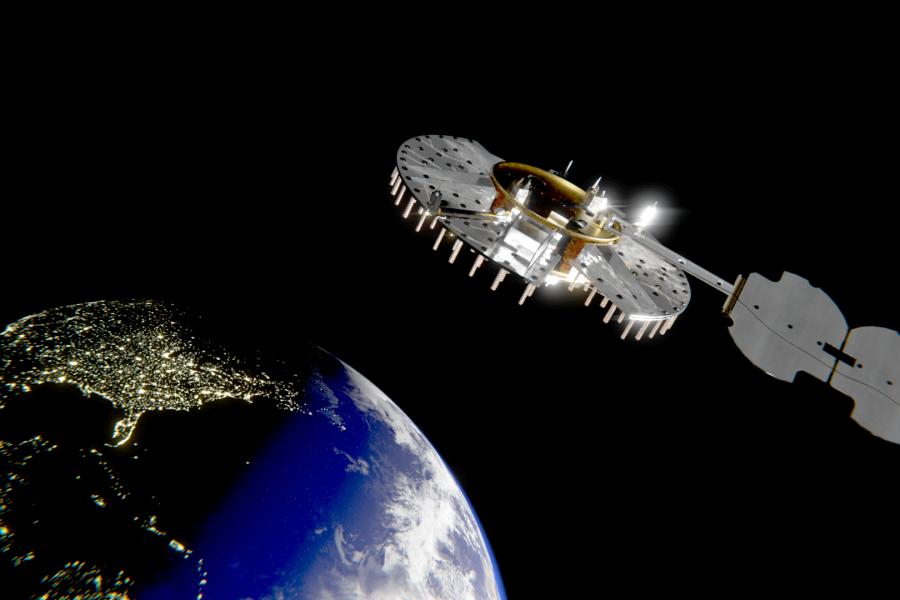

Lockheed Martin has been working on GPS for more than a decade, winning a contract from the Air Force in 2008 to develop the constellation’s GPS III satellites, followed by the GPS III Follow-on program in 2018.

And the system has been extraordinarily successful. “GPS is the world standard [and] will remain the world standard for a long time,” Vice Chief of Space Operations Gen. David D. Thompson told Congress in May.

Caldwell credited that success in part to the focus on the system as “software enabled,” so that improvements can be made rapidly.

“We’ve been able to evolve the technology over time,” Caldwell said. “So that first GPS III that we launched in December 2018 … we’ve evolved that product line along the way. … We’re constantly upgrading the software and how it operates to deliver performance. It’s modular, so we can constantly pull in the latest technology to make sure that it’s resilient.” Since that December 2018 launch, four more of Lockheed’s GPS III satellites have gone into orbit. Three more have been declared available for launch. At the same time, the contractor has developed a ground control software update that is helping to operationalize the ultra-secure and jam-resistant M-code signal.

But at a certain point, GPS has become almost too successful, Thompson noted to lawmakers, saying “it is perhaps fair to say that we’ve come to rely on it solely and exclusively and too heavily.”

Both China and Russia have tested antisatellite weapons in recent years, creating new urgency in the Pentagon to develop a resilient space architecture. And while much of that resiliency talk has focused on the Space Development Agency’s data-transport and missile-tracking constellations, PNT has gotten some attention, too.

The Air Force Research Laboratory is on the verge of launching the third Navigation Technology Satellite, or NTS-3, in 2023. One of the Air Force’s first PNT demonstrations in decades, it is also slated to become a program of record. The satellite will help AFRL test “advanced techniques and technologies to detect and mitigate interference to PNT capabilities and increase system resiliency,” according to the lab’s website.

The Air Force is not alone in paying more attention to PNT. Thompson noted in May that the Army is actually leading the way on that front, with the Navy and Air Force following closely, and Caldwell told Air Force Magazine that other countries’ militaries have also been looking into the issue for some time now.

“The Australians have been enormously interested in the future for something like PNT augmentations,” Caldwell said. “So you get precise, we call it precision pointing—you get an augmented system. And they’ve invested heavily with us in a testbed.”

The United Kingdom is another country that is considering how it might rethink PNT, Caldwell said, sparked in part by the country’s departure from the European Union and corresponding departure from Europe’s GPS alternative, Galileo.

Indeed, during the Farnborough airshow, the British government announced that later this year, it will be launching a satellite that will provide “an innovative new signal … to provide data from space that can be used on the ground to obtain a position or an accurate time.”

And despite its heavy involvement in the GPS program, Lockheed Martin is eager to partner with other companies or governments interested in further developing the future of PNT, Caldwell said.

“There are interesting and unique technologies coming into play, and we are trying to find ways to put as many of those into test beds as we can to get real-world on-orbit data,” Caldwell said. “And we’re very focused right now on these demonstration platform sets, demonstration satellites, and finding different companies to partner with and say, ‘Hey, if you’ve got a great idea, … what could that mean for timekeeping?’”

The implications, he noted, could be far-reaching.

“What would PNT look like in lunar, cislunar space? How would a cislunar PNT [vehicle] operate with a terrestrial PNT system?” Caldwell posed. “Someday, gosh, we’re going to get to Mars, right? So what is Martian PNT going to look like? Because eventually there’ll be enough rovers or one day even people to be there and they’re going to arrive and be like, ‘Where am I’ if there’s not a system in place. So I think now’s a really good time to be experimenting.”

Already, the Space Force has started considering how it will monitor and police cislunar space. Chief of Space Operations Gen. John W. “Jay” Raymond predicted in January that the service will need cislunar space domain awareness within five years, and AFRL is already seeking input for a satellite to do just that.