Special-ops aviators, a physicist from the intelligence community, and an enlisted Marine with decades of deployments: U.S. Space Command’s military and civilian leaders who spoke May 7 were as likely to come from strictly space backgrounds as not.

Several of the newest combatant command’s top officials appeared during a Space Foundation virtual Symposium365 talk. They indicated that their diverse backgrounds are by design and that few Space Force personnel are yet a part.

Some of the day’s insights from inside the command, which was re-established 19 months ago and whose geographic area of responsibility starts 100 kilometers above the surface of the Earth:

More Partners, More Deterrence

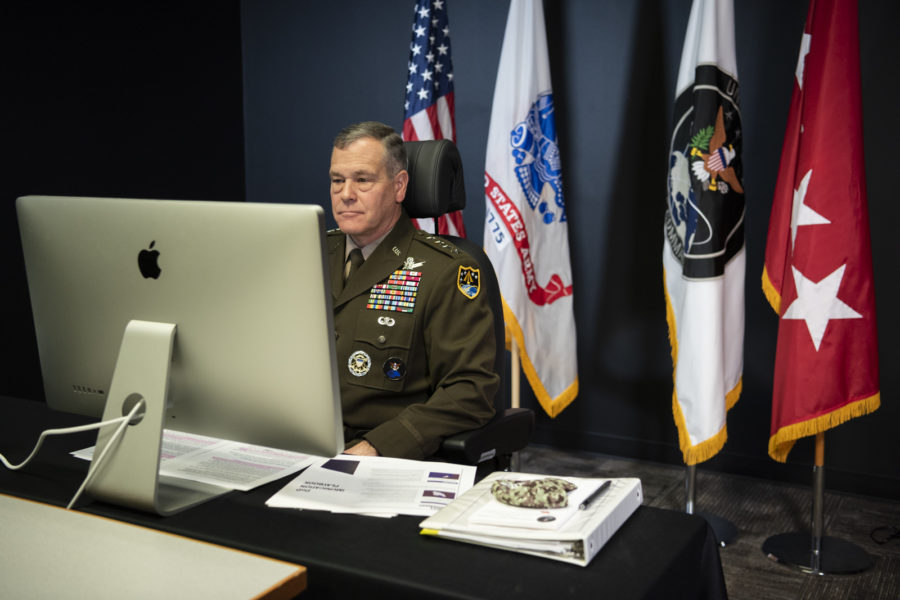

Army Gen. James H. Dickinson leads U.S. Space Command from its provisional headquarters at Peterson Air Force Base, Colorado. He said more allied and partner organizations will be “physically coming to work” at Peterson over the next 12 to 18 months and he sees “that energy expanding.”

“When I look at deterrence, one of our strongest deterrence capabilities, or measures, within the command is that strong allied and partner integration that we have,” said Dickinson, whose background is in missile defense. “We are starting to see a lot more allies that want to be … part of the space enterprise, want to work with U.S. Space Command,” he said. “So our ability to be able to capture that energy and start bringing those folks into the command itself is very powerful.”

The Department of the Air Force selected Redstone Arsenal, Alabama, as U.S. Space Command’s permanent home pending an environmental review, though the selection is under review.

One way U.S. Space Command tries to expand the pool of international partners is by inviting countries to take part in the Global Sentinel exercise in space situational awareness started by U.S. Strategic Command, said Space Force Col. Devin R. Pepper, deputy director of U.S. Space Command’s Strategy, Plans, and Policy Directorate and garrison commander of “soon-to-be Buckley Space Force Base” in Colorado. Pepper was nominated to be a brigadier general in January.

Ten partners including the U.S. took part in the last Global Sentinel in 2019. Pepper mentioned Chile and Poland as prospects. He said the invitations serve “as a lead-in to signing space situational awareness agreements with these partner nations.”

Warfighting Dynamic

Air Force Maj. Gen. William G. Holt II said he “didn’t have much experience with the space domain” before becoming U.S. Space Command’s director of operations, training, and force development.

A career special operations pilot, he characterized the command’s makeup as “actually very joint” and “kind of an even mix of Air Force background, Army background, Navy background—we have a handful of Marines, including our director of our cyber operations is a Marine one-star—and then, actually, not a whole lot of Space Force officers at this point in time,” Holt said.

Holt credited Space Force Chief of Space of Operations Gen. John W. “Jay” Raymond with the level of jointness intended “to change the dynamic and really bring in a warfighting … viewpoint from across the force.

“I’m not saying that the old Air Force Space Command wasn’t warfighters, because they absolutely did that every day—they supported us; they deployed downrange—but having the different backgrounds as far as the different services, I think, was really critical to [Raymond] bringing me in.”

Farther Reach

As space becomes more accessible, the command is looking ahead to when the military will want to operate beyond Earth orbit.

“More and more nations are operating in space,” said U.S. Space Command’s senior enlisted leader, Marine Corps Master Gunnery Sgt. Scott H. Stalker. He cited the United Arab Emirates’ Hope Mars Mission, a satellite that arrived in orbit around the red planet in February, “the first planetary science mission led by an Arab Islamic country.”

Stalker previously served as the senior enlisted leader for the National Security Agency, the Defense Intelligence Agency, and U.S. Cyber Command, along with numerous deployments around the world and acknowledged that, “We are no longer the undisputed leaders in space.”

To be in position to gather intelligence in deep space soon enough, U.S. Space Command’s Deputy Director of Intelligence physicist Sean M. Kirkpatrick said the U.S. needs to take advantage of space technology the commercial sector is already working on.

“We’ve got a huge moon competition going on. We’ve got a Mars competition going on—multiple countries heading out,” Kirkpatrick said. “We are going to have to extend our mission space to the cislunar, lunar, and Martian orbits and regimes at some point in the not-too-distant future.”

The customary five- to 10-year timeframe for a defense acquisition program would take too long, he said:

“We’re going to be far behind … So we need to look forward now on, ‘What do I have to put in cislunar orbit, or [what] do I need to put in lunar orbit, just to be able to monitor activities that are going on and report that back.?’”

Then and Now

Having flown helicopters by map while stationed in Germany prior to the advent of GPS, then later, during Operation Desert Storm when GPS was brand new and unreliable, Army Brig. Gen. Thomas L. James said the experience of having space as a resource, then having it disrupted “at a time that you didn’t really anticipate,” have made the mission at U.S. Space Command “so visceral and passionate” to him personally.

“As we deployed to Desert Storm, we were handed a small number of sets of GPS systems, and we just learned how to integrate those on the fly as we went into combat operations,” James said.

“The way they operated then—because it was only a partial constellation—is some of the time, you knew where you were with great precision. Some of the time, you knew that you didn’t know where you were at all based off of the GPS. And some of the time, you thought you might know where you are.”

He learned “what it meant to lose our access to space—to have that day without space.”