JOINT BASE MCGUIRE-DIX-LAKEHURST, N.J.—Then-Capt. Rob McAllister was a brand new aircraft commander in November 2004 when he was flying over Fallujah, where U.S. Soldiers and Marines were fighting a fierce battle in the streets of the Iraqi city. Flying a KC-10 tanker, McAllister pulled long hours refueling coalition aircraft flying in to provide close air support for ground troops.

“As the Navy F/A-18s and F-14s came up to refuel, they had less bombs on the rack, and there were more plumes of smoke in the city, because they were trying to protect the guys on the ground,” McAllister told Air & Space Forces Magazine. “We provided a lot of flexibility to the fight, helping guys stay on station longer. That happened all the time.”

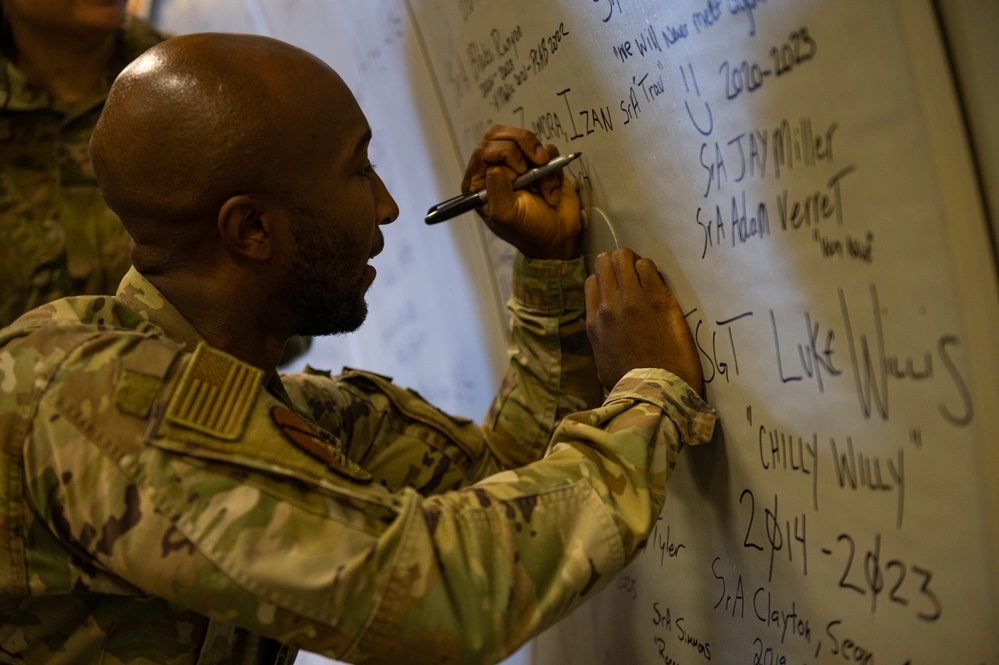

Nearly 20 years later, McAllister is now a colonel with 5,328 flight hours on the KC-10, more than any other Active-Duty pilot. This week, he and several hundred other Airmen past and present gathered with friends and family members under drizzly, overcast skies at Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst, N.J. to see the last KC-10 stationed there take its last flight to the 309th Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group, also known as The Boneyard, in Arizona.

With 42 years of service under its belt, the KC-10 can carry more than 356,000 pounds of fuel, almost twice the amount a KC-135 can haul, and nearly 170,000 pounds of cargo, almost matching the capacity of a C-17.

“I don’t know how many missions we’ve done where we’ll carry a unit’s cargo, drag the fighters, and bring their maintenance with us,” said Master Sgt. Andrew Leo, a flight engineer with 10 years of experience in the KC-10. “We’ll go somewhere like ‘All right, we’re all here, here’s your entire air wing.’”

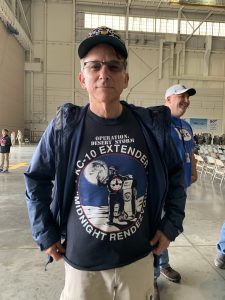

The Extender, affectionally known by many Airmen as ‘Big Sexy’, first arrived at then-McGuire Air Force Base in 1994 before flying in military operations and humanitarian missions around the world. The last jet to leave, tail number 84-0188, has 33,017 flight hours, with 11,000 or so air crew members helping to refuel 125,000 U.S. and coalition receivers from 25 different countries. Another 12,000 maintainers worked on the aircraft over its 39-year career.

And that’s just one of the 60 KC-10s the Air Force has operated, 32 of which have been based at Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst.

“Projecting America’s airpower, standing watch over America and delivering hope … that’s the legacy of the KC-10,” Lt. Gen. James Jacobson, deputy commander of Pacific Air Forces, said at the farewell ceremony on June 21. An old hand on the KC-10, Jacobson flew from Hawaii for the honor of piloting the tanker on its final journey to the Boneyard. He choked up at the thought of it during his speech.

“I’m thankful for the opportunity to do what I think everybody else in this room would want to do, which is say thanks,” he said.

The KC-10s both at McGuire and at Travis Air Force Base, Calif., are being retired to make way for the KC-46 as part of the Air Force’s recapitalization of its tanker fleet.

“We should have bought 160 of those things [KC-10s] and we will regret it for the rest of our time, but sometimes you make fiscal decisions you don’t like,” said Jacobson, who later added that the aircraft is aging out of use.

“America can’t afford to make the spare parts to make an airplane that almost is out of service across the globe,” he said.

The good-bye was made more bittersweet by the fact that some KC-10 Airmen will not be making the jump to the KC-46. Leo will work a ground job, perhaps with Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst’s Contingency Response Wing. Tech Sgt. Tiffany Irby, a refueling boom operator with about 10 years of experience on the KC-10, is going to nursing school and hopes to work in aeromedical evacuation.

No matter where they go next, they will carry memories of the KC-10 with them. Chief Master Sgt. Ryan Guerrette, a maintainer who worked on only KC-10s throughout his 29-year career, remembered coming in on Sept. 11, 2001 to put a KC-10 back together that had been partly disassembled for an inspection, a two-day task under normal circumstances.

“Within 12 hours that aircraft was put back together, out on the flightline, refueled and airborne, ready to start this war on terror,” he said. “That was just an insane moment, everybody came together, got the aircraft inspected and serviced, and it was gone.”

The KC-10s first flew over the East Coast to refuel fighter jets performing combat air patrol, but within a week they were deployed to support combat operations over the Middle East. Leo remembered plenty of times over Afghanistan being at just the right spot to give a combat jet the gas it needed to keep providing close air support for troops in contact.

“One thousand pounds of fuel for us is nothing, but it’s everything for an A-10 that needs to do a couple more gun runs,” he said. “That long day, that 10-hour day makes sure we can be there to support the minutes or seconds that matter.”

Not all the KC-10’s missions were combat-focused. Irby remembered flying on an Extender filled with bags of rice and roof trusses for a humanitarian mission in the Caribbean.

“Somebody was getting fed and somebody was getting a roof over their head,” she recalled.

On one unusual mission, Guerrette remembered refueling a C-17 on its way to Ascension Island, in the middle of the south Atlantic, to pick up a family of Cheetahs on their way from Namibia to the Cleveland Zoo.

Due to their long range and large fuel load, KC-10 crews often spent 12 hours or more on a single sortie, and that often led to crews embarking on culinary adventures using the jet’s two small ovens. Leo recalled one ambitious co-pilot attempting to bake a quiche, while Irby recalled chicken fingers, salads, spaghetti, and pizza made on pita bread scrounged out of the base dining facility (DFAC).

“It’s usually whatever you can find in the DFAC,” said Irby who, as the boom operator, also served as the crew’s de facto cook. “You do what you have to do, because you never know how hot that oven is actually going to get.”

As the boom operator, Irby also worked closely with the pilots of the receiving aircraft. She recalled playing trivia with receiving fighter pilots and listening to them recite from a book of dad jokes.

For both Irby and Leo, the fondest experiences aboard the KC-10 were seeing young aviators gain experience and confidence aboard the jet, especially when they have a “light bulb” moment understanding their role in the crew. Irby said many of those Airmen are taking that experience over to the KC-46.

“It’s rewarding in the sense of ‘I helped you get there and I’m very proud of you,’” she said.

Yet even as Airmen bade farewell to the aircraft, Jacobson hinted that the Air Force’s days of needing the the KC-10 may not be over as the service prepares for a potential conflict over the vast reaches of the Pacific.

“My hope is—my expectation is—it will find another life, along with all the other jets still at Travis, to continue serving America. My concern is we need it now to help forces get ready, and we may need it in the future if deterrence fails,” Jacobson said. “Fuel matters if deterrence fails in the Pacific, and nothing delivers fuel like the KC-10.”