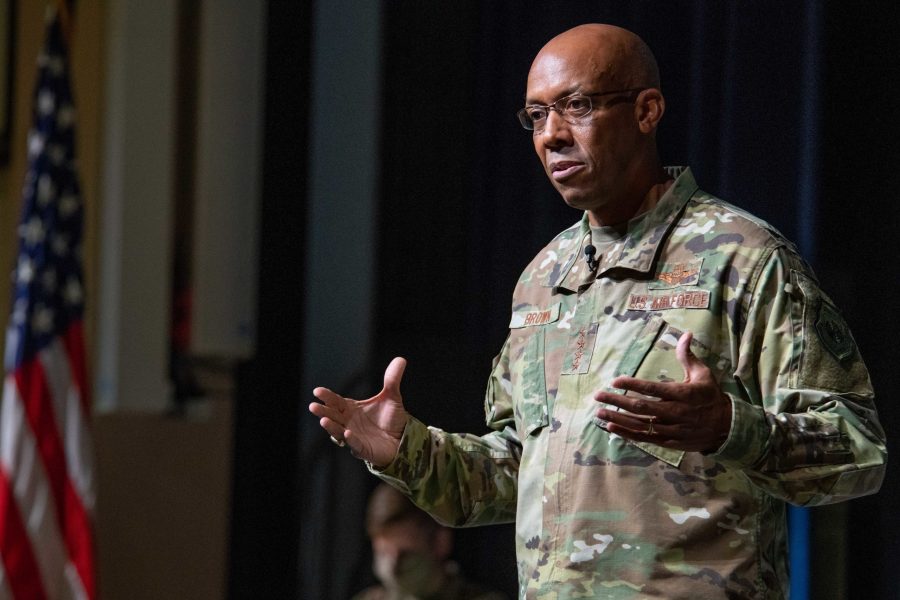

The military needs to rethink the way it develops and approves strikes in combat and possibly restructure component commands as the Air Force-led joint all-domain command and control effort to connect sensors and shooters in real time takes root, Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr said.

The Advanced Battle Management System demonstrations this year, in which dozens of aircraft and sensors feed into a cloud-based picture of a battlefield, shows that the established way of selecting targets and fires is too slow and cumbersome to be effective in the future.

Under current doctrine, a Joint Targeting Coordination Board composed of several officials, including military leaders, representatives from external agencies, multinational partners, and subject matter experts from areas such as intelligence and operations, develops targeting priorities. But if the military can bring together its sensor and shooter information instantaneously, “We’re not going to be able to have boards with humans in the loop that actually sit down and kind of validate targets,” Brown said during a virtual National Defense Industry Association conference on JADC2.

Instead, as the military develops JADC2, it needs to write its algorithms to take into account the risk associated with targets and the best weapon system to use to strike.

“It requires some thought process for us to build the algorithms, so we can put them into the system and it goes through and says in real time, ‘If you find that target and it meets all of that criteria, then you’re able to engage it,’” Brown said.

There needs to be human involvement, just not at the scale of a targeting board of several officials, Brown added. A human presence “on the loop” watching the target development can confirm it “using some human judgment. But that’s the way you can move faster, so you’re really doing almost a Joint Targeting Coordination Board in real time, using the tools to actually provide options,” he said.

If the JADC2 vision comes to fruition and is used in deployed areas, there needs to be a discussion on “how we organize ourselves,” Brown said. For example, will there still be a need for separate air, land, and sea component commanders if the goal is to fuse all sensors and shooters from each domain?

“Because each of those component commanders need to understand all of those domains,” Brown said. “They may have expertise in their domain, but they’ve got to understand them all in order to be effective.”

The Air Force within the past year has led the charge to joint all-domain command and control, largely with three ABMS “on-ramp” experiments. The second event in August, for example, brought together dozens of sensors and different shooters such as USAF aircraft, Army artillery, and Navy ships, to down a cruise missile threat.

The on-ramps have shown that the defense industry has a large role to play in this evolution, especially since “non-traditional” companies can provide different capabilities in the realms of cloud-based software and communications, for example. The Air Force wants to show it can move beyond the typical acquisition process to move faster and bring in new companies that can translate successful systems already in use in the commercial world for the military.

Brown said companies now need to take into account this broad outreach, and develop weapons systems that can talk with others in a joint language instead of operating in a proprietary way. The Air Force “doesn’t want to spend money on a system that doesn’t connect,” he said.

New systems need to be updated regularly, like mobile software that can be updated on the fly. “What we don’t want to do is build a one-off. We actually should build something that can be upgraded fairly quickly, can be adaptive, it can stay with the times,” Brown said. These systems should use 5G because, “We don’t want to actually still be on 3G and 4G and everybody else is on 5G, and we wonder why things are taking so long, and we’ll get that blue spinning circle on our computers.”