Experts warned the Senate Armed Services Committee at a Jan. 12 hearing that approving a waiver for retired Army Gen. Lloyd J. Austin III to serve as Defense Secretary would damage the norm of civilian control of the military and cautioned against relying on veterans to lend credibility to American politics.

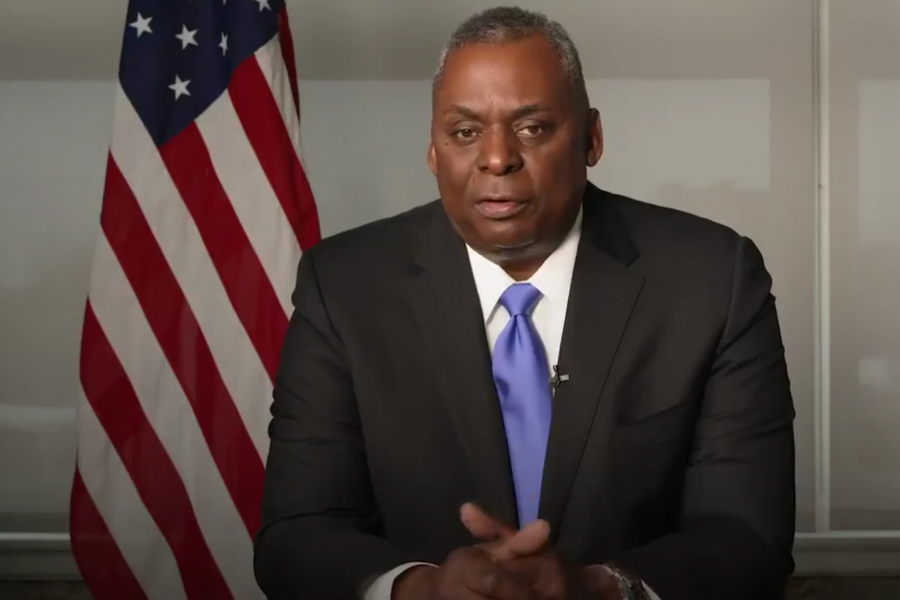

President-elect Joe Biden said in December he would turn to Austin, a former U.S. Central Command boss who would be the first Black Defense Secretary if confirmed, to run the Pentagon. Austin left military service in 2016 and needs a congressional waiver to hold the Defense Department’s top civilian job because he has not yet been retired for seven years.

“Secretary-designate Austin is going to work tirelessly to get it back on track,” Biden said of civilian-military relations last month. “There is no doubt in my mind whether this nominee will honor, respect, and on a day-to-day breathe life into the preeminent principle of civilian leadership over military matters in our nation.”

Senators are now in the position of deciding whether to waive that seven-year requirement for only the third time in U.S. history and the second time since 2017. It’s not only a matter of whether he has the integrity or the respect to lead, they said, but what is at stake by allowing him to do so.

The question of whether Austin is truly the best candidate for Defense Secretary hung over the hearing, one week before the secretary-designate is slated to appear before the committee. The House Armed Services Committee plans to vet Austin at a similar hearing on Jan. 21.

Lawmakers appeared to mull whether Austin’s nomination is fundamentally different enough to deny his waiver compared to President Donald J. Trump’s pick of former Marine Corps Gen. James N. Mattis. Many saw Mattis’s selection as a chance to boost the amount of government experience in Trump’s cabinet, as well as to introduce a check on potentially dangerous presidential requests.

Lindsay P. Cohn, an associate professor at the U.S. Naval War College who testified before the panel, said Mattis’s time as Secretary raised the issue of over-deference to the military voice in the room, as well as to the friends and colleagues of civilian officials with military experience.

“No one is worried” about the waiver decimating civilian control or the integrity of American democracy altogether, Cohn said. What is at stake is weakening those norms and institutions, she said.

“Choosing a recently retired general officer and arguing that he is uniquely qualified to meet the current challenges furthers a narrative that military officers are better at things and more reliable or trustworthy than civil servants or other civilians,” Cohn said. “This is hugely problematic at a time when one of the biggest challenges facing the country is the need to restore trust and faith in the political system. Implying that only a military officer can do this job at this time is counterproductive to that goal.”

Answering questions about the value of former generals as apolitical figures in hyperpartisan Washington, Cohn suggested that Mattis and retired Army four-star George C. Marshall were not “shining examples” of the best candidates for SECDEF. Instead, it’s often Secretaries with past political and legislative experience across a range of issues who are best equipped to take on the complexities of DOD.

Kathleen J. McInnis, an international security specialist with the Congressional Research Service, noted at the hearing that the U.S. has seen how the influence of retired generals who move to the civilian staff has manifested down the chain of command for planning and oversight, particularly in cases where the Joint Chiefs of Staff and their employees overshadow the work done in the civilian-led Office of the Secretary of Defense.

Senators have to decide that the value of a person’s contribution as SECDEF would outweigh that damage of approving another waiver, Cohn added. But greenlighting Austin to serve doesn’t mean future nominees with military backgrounds will be shoo-ins: “You can change the direction of that norm,” she said.

Though Austin may not end up facing much opposition in the final waiver and confirmation votes, SASC members in both parties raised questions about why Biden sees Austin as the best fit for the job and what the ripple effects of another former general in charge may be.

Outgoing Chairman Sen. Jim Inhofe (R-Okla.) raised the question of whether Biden as commander-in-chief would hear enough diverse opinions because the Pentagon’s top civilian and military officials—Austin and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Mark A. Milley—both come from the Army. He wondered whether tapping Mattis and Austin has contributed to further politicization of the military.

“After 40 years of successful military service, it would be natural and comfortable for Lloyd Austin to surround himself with previous military colleagues … rather than selecting or recommending strong civilian candidates for senior service and military service,” Inhofe added.

Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va.) worries Austin’s career ties to the Pentagon may blind him to changes that need to be made or deter him from pursuing them. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.), the only senator to vote no on Mattis’s confirmation in 2017, similarly questioned whether tapping a former Soldier would discourage women who fear being raped or murdered by their fellow troops that those problems wouldn’t be taken seriously at the top.

Democratic Sens. Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut and Tammy Duckworth of Illinois oppose granting a waiver. Others, including Maine Independent Sen. Angus King, are still wrestling with the decision.

It risks “creating a danger that the exception will swallow the rule,” Blumenthal said. “It is a matter of principle.”

Still, Blumenthal said Austin has alluded to measures he could take to strengthen civilian control, such as taking back some of the power that has fallen to the uniformed Chiefs of Staff.

The experts stressed that Austin should be transparent with press and with lawmakers, and discuss how he differentiates between his military and civilian roles as well as how he plans to empower the civilian side of the house.

Confirming Austin will make restoring the electorate’s trust in American politics more difficult, Cohn said, and forces the Biden administration to work harder to build a strong national security civilian corps. If numerous defense jobs are left without formally appointed and Senate-confirmed staffers, as has happened throughout the Trump administration, those security matters will fall to agencies that are adequately staffed, McInnis added.

Top civilian posts, like deputy defense secretary and the Pentagon policy boss, should be filled as quickly as possible, the experts said. Biden is nominating Kathleen H. Hicks to be deputy defense secretary and Colin H. Kahl as undersecretary of defense for policy.

Over time, the statutory limitation on former troops serving as SECDEF has shrunk from 10 years to seven years—a move that can be interpreted as weakening the firewall between military and civilian service. But Congress has also implemented the seven-year waiting period for other civilian positions in DOD as a way to strengthen civil service overall, McInnis said.

“It’s not just the person of the Secretary of Defense and the particular qualities that they bring to the game,” she said. “It’s also, who are the service Secretaries? Who are the undersecretaries? Do they have, together as a team, the set of skills … this chamber feels is necessary to accomplish the national security business of the United States?”