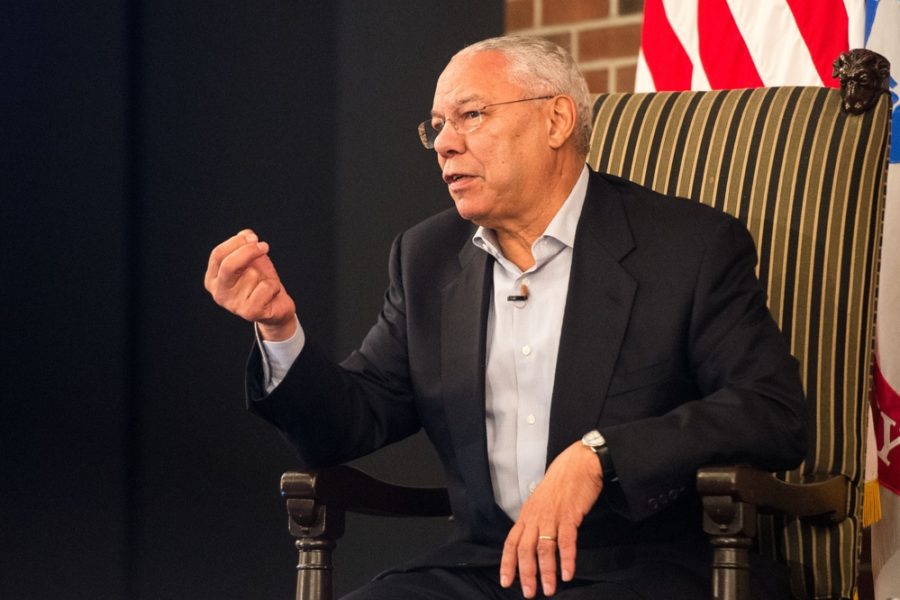

Colin Luther Powell, U.S. Soldier, diplomat, and statesman, died Oct. 18 at the age of 84. As Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, he advised President George H.W. Bush during America’s response to Iraq’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait and the ensuing swift victory in the 1991 Gulf War. He also presided over the invasion of Panama and a sharp reduction in the size of the U.S. military after the end of the Cold War. His public stature was such that he was courted by Republicans and Democrats alike to be a presidential candidate, but he declined the offers. Powell faulted himself for not arguing more forcefully against a second war in Iraq while he was Secretary of State; in later years, he was a popular author and speaker.

His death was attributed to complications from the COVID-19 virus; a breakthrough case, as Powell was fully vaccinated, but in recent years he had suffered from blood cancer that severely degraded his immune system.

Powell achieved a number of firsts for a Black man: the first to be Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, first to be Secretary of State—the only person to hold both positions other than George C. Marshall, who did so under President Harry S. Truman—and the first to be National Security Advisor. He was only the fourth Black man to be a four-star Army general. Powell was considered to be the least apolitical general since Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Raised by immigrant Jamaican parents in the South Bronx, Powell attended New York City College and found his calling with the ROTC program there. He was commissioned in the Army and enjoyed a meteoric, 35-year career that included two tours in Vietnam. He rose to the rank of brigadier general by the age of 42, and after serving as military assistant to Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger and command of V Corps, Powell was tapped by President Ronald Reagan to be National Security Advisor.

At the White House, Powell, still on Active duty as a three-star general, advised Reagan on arms agreements and renewed détente with the Soviet Union, coming to national attention and establishing him in the inner circle of foreign policy experts. Though peripherally involved in the “Iran-Contra” scandal of selling weapons to Iran to create funds for the anti-Sandinista movement in Nicaragua, he was not publicly identified with it. He left the White House in 1989 to become the four-star head of Army Forces Command. Just a few months later, however, Powell was appointed to be Chairman of the Joint Chiefs by President George H.W. Bush.

Late that year, Powell and Bush approved plans for a toppling of the Manuel Noriega regime in Panama. Called “Operation Just Cause,” which was executed in just over a month’s time, the invasion was ostensibly meant to protect access to the Panama Canal.

In August 1990, Iraqi strongman Saddam Hussein seized Kuwait. Powell advised that U.S. reaction be heavy and include internationally ironclad economic sanctions, but Bush decided, without consulting Powell, to reverse the invasion militarily. The buildup of U.S. forces in Saudi Arabia and surrounding coalition nations to deter and eventually defeat Iraq was called Operation Desert Shield.

Shortly after the buildup began, newly minted Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Michael J. Dugan gave a series of candid interviews with reporters traveling with him to inspect preparations in the Middle East. Dugan argued that if war came, a massive application of airpower would be required to whittle down the Iraqi Army, and that one goal would be to decapitate Iraq’s leadership. Soon after publication of the remarks, Dugan was fired by Defense Secretary Dick Cheney, who said Dugan had given away too much information about war plans, even though most of what Dugan said had already been revealed in the defense press. Powell said little publicly about the firing, except that he concurred with it, but Pentagon insiders said Powell urged Cheney to fire Dugan, as Powell believed Dugan was over-promising what airpower could accomplish.

In a November 2017 interview with the San Diego Union Tribune, former Chief of Staff Gen. Merrill McPeak, who Bush and Cheney picked to replace Dugan, said that after his own inspection tour of Desert Shield preparations, he told Bush that the Air Force and other service air arms were “ready to go” but that Powell “was trying—I thought—to delay operations until the Army got ready.” McPeak added that, “My experience with the Army is that if you wait until the Army’s ready, forget about it,” noting that 8th Air Force attacked Germany in World War II well before a land invasion could begin.

Powell eventually acquiesced to a war plan created by Army Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf, which closely followed what Dugan had laid out. Briefing the press at the outset of Operation Desert Storm, Powell said the U.S. plan regarding the Iraqi army was, “We’re going to cut it off, and we’re going to kill it.” In the actual conflict, air forces conducted a highly successful six-week bombing campaign that halved the Iraqi military, followed by a four-day ground operation. Air attacks continued during the ground offensive, but Powell told Schwarzkopf to stop them, as it had effectively become a slaughter that Powell believed would hurt U.S. standing in the world. Powell, Schwarzkopf, and other commanders were honored in a New York City ticker-tape parade in June 1991.

In what became known as “The Powell Doctrine,” which he adapted from his former boss, Caspar Weinberger, Powell in 1992 laid out ground rules or tests the U.S. should check off before entering an armed conflict. It stipulated that the cause must be vital to U.S. security; the public be behind it; that overwhelming force should be applied to achieve rapid victory; and that an exit strategy must be set before the fighting starts.

After Desert Storm—and the self-dissolution of the Soviet Union—Powell implemented a reduction in the size of the U.S. military ordered by Bush. The “base force” concept saw about a 25 percent reduction in the force overall, with some aspects—Air Force combat airpower and personnel being one—seeing as much as a 40 percent reduction.

Powell was a holdover to the presidency of Bill Clinton, who advocated even deeper cuts to provide the nation with an economic “peace dividend” of winning the Cold War. Powell balked at the size of further reductions but acquiesced to some lesser cuts, particularly in the manning of the military services.

He resisted Clinton’s moves to allow gay men and lesbians to serve in the military, which eventually led to the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. During his months serving under Clinton, Powell also pushed back against using force against Serbia in response to its genocidal campaign against Muslims in the Balkans—again preferring sanctions—and he supported allowing a weakened Saddam Hussein to remain in power in Iraq, as a hedge against Iran. Powell’s final days as Chairman were marred by the “Blackhawk Down” incident in Somalia, when he and Defense Secretary Les Aspin were criticized for failing to provide adequate protection for Army troops operating in that country.

Powell wrote a memoir called “My American Journey” about his humble beginning and success, and advice on leadership. He became a hot speaker, drawing six-figure fees. Admired by most Americans, he was approached to run for President but decided in 1995 he did not have the “fire in the belly” to be President. Though a lifelong independent, he eventually declared himself a Republican and spoke at Republican conventions, but in recent years distanced himself from the party over the policies of President Donald Trump.

Powell was the first Cabinet appointee of President George W. Bush, serving as his first Secretary of State, receiving unanimous Senate confirmation. During his tenure he reinvigorated the State Department and modernized it with new technology and communications gear. Powell clashed with both Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney on a number of foreign policy matters, including how to handle North Korea’s nuclear ambitions, which Bush wanted to confront.

Powell helped organize an international response to the 9/11 attacks, but it was a narrower coalition than in the 1991 Gulf War.

He argued against Bush’s desire to engage in a second Iraq war, arguing that if the U.S. conquered Baghdad, it would assume the expensive responsibility for feeding and policing that nation until a new government could be installed. He later wrote that he did not argue forcefully enough against Operation Iraqi Freedom, feeling that Bush had already decided to attack and that Powell’s counsel would be devalued if he continued to oppose the war.

In a February 2003 speech at the United Nations, Powell presented the case that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction that he might give to terrorists, and could not be left in power, citing U.S. intelligence. Powell’s reputation and authority swung public and world opinion, but the intelligence eventually proved faulty, and he later said in an ABC news interview that his U.N. speech would be a permanent “blot” on his reputation, a “painful … part of my record.”

In his book, “It Worked for Me: In Life and Leadership,” Powell said he was “mostly mad at myself for not having smelled the problems” in the run-up to the second Iraq war, saying his instincts had failed him.

Powell did not stay for a second Bush term, insisting he always planned to serve just one term, leaving government service in 2004.

In retirement, Powell lent his name and money to a number of causes. City College created the Colin Powell School of Civic and Global Leadership, for which he served as chairman of the board of visitors. In 1997, he created America’s Promise, an organization to help at-risk children. He endorsed President Obama’s presidential bid in 2008 and served as an adviser during Obama’s administration. In 2016, he said he would not endorse Trump’s candidacy, and in 2020, he accused Trump of having “drifted away from” the constitution.

Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin III said “the world [has] lost one of the greatest leaders that we have ever witnessed,” saying Powell was a “personal friend and mentor. He always had great counsel.” As a Soldier and statesman, Powell “was respected around the globe … It is not possible to replace a Colin Powell. We will miss him.”

McPeak, asked for comment, said, “Colin was a good guy—smart, but also possessing considerable charm, while at the same time being a ‘man’s man.’” Powell was “a world-class bureaucratic in-fighter. I never won an argument [with him], even though I was usually right.”

Retired Lt. Gen. Bruce “Orville” Wright, president of the Air Force Association, praised Powell’s leadership.

“General Powell was a warrior-statesman whose leadership was foundational to America’s overwhelming victory in Operation DESERT STORM,” Wright said. “His support for Gen. Norm Schwarzkopf and Lt. Gen. Chuck Horner ensured the effectiveness of combat air forces and empowered our Airmen to be effective at every level. His standing among warfighters, and the American people remained strong to the end and was a compelling testament to his enduring strengths as a leader.”