If the Air Force and Pentagon decide the F-35 fighter needs an all-new engine, it wouldn’t just give the jet range and performance improvements—it would drive a refresh of the entire fighter propulsion industrial base, a GE Aerospace official claimed Feb. 16.

Competitor Pratt & Whitney, however, says putting a brand new engine on the F-35 would hurt future development for programs like the Next Generation Air Dominance fighter.

Speaking with reporters about GE’s XA100 Adaptive Engine Transition Program (AETP) powerplant, vice president and general manager of advanced combat engines David Tweedie said he is anticipating the upcoming fiscal 2024 defense budget will include a decision on the future of F-35 propulsion.

GE Aerospace is rooting for that decision to include AETP, which would put it back in contention to power F-35 fighters.

A new powerplant means “an opportunity not just to continue making legacy architecture/legacy-type engines that are currently in production, but to actually fully modernize” the fighter engine industrial base with “the latest technologies,” including many that are in commercial products but “have not yet been introduced into production fighter engines,” Tweedie said.

“It’ll provide a modernized, diversified and more resilient [military engine] industrial base in the United States,” he added.

Competitor Pratt & Whitney, meanwhile, continues to argue in favor of a more incremental upgrade to its current F135 engine.

“AETP technology is best suited for sixth-generation platforms, not the F-35,” Jen Latka, F135 vice president at Pratt, said in a Feb. 16 email to Air & Space Forces Magazine. “A brand-new F-35 engine will unnecessarily disrupt the program of record and divert billions from advanced sixth-gen propulsion solutions,” she said.

Pratt & Whitney has had been the F-35’s sole engine-maker since GE was locked out of the program in 2011. Both companies developed AETP powerplants under yearslong, multi-billion dollar Air Force contracts geared to providing greater range and power to the F-35 at midlife, but the Air Force hasn’t said yet whether it needs or can afford to develop a new F-35 engine.

The F-35 Block 4 needs more power and cooling capability to run its new capabilities, however, so no change at all isn’t a choice.

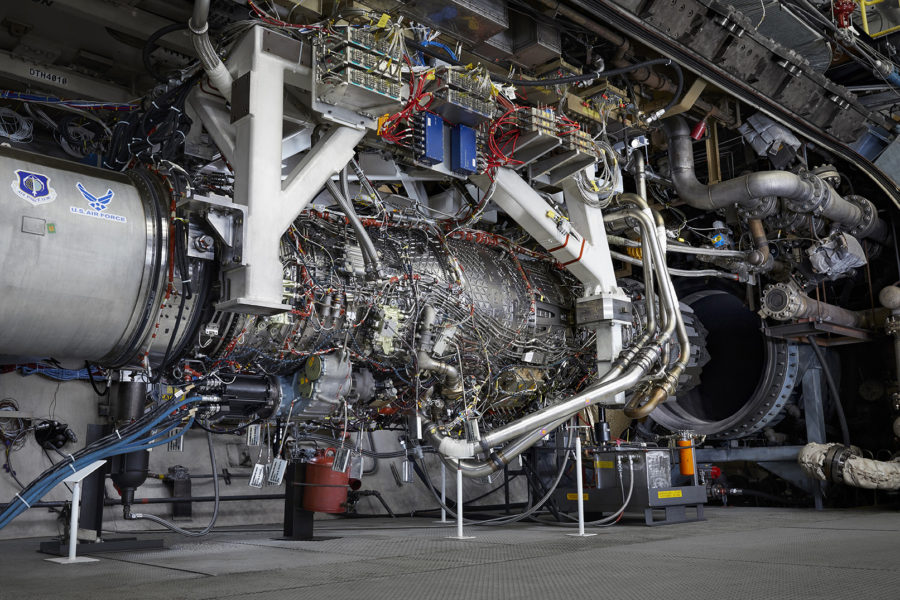

To keep its options open, Congress appropriated $203 million late in 2022 for further development of AETP engines, which Tweedie said GE is using to “burn down risk” on its XA-100 version and keep a team of some 400 engineers together. GE has dubbed this effort “Design and Manufacturing Advancement”—a term Tweedie said describes activities akin to Engineering and Manufacturing Development—which will leverage data collected in prototyping and begin production design; continue airframe integration efforts with Lockheed Martin, and sketch out logistics and sustainment plans.

Pratt & Whitney also has an AETP engine to offer, but it has instead pitched what it calls the F135 Engine Core Upgrade, which would allow the company to keep its F-35 monopoly. Latka said in December that company believes the ECU approach would save $40 billion versus an all-new powerplant, counting development and integration costs and the need to flesh out a global support enterprise with new engines and parts.

“Our F135 Engine Core Upgrade will incorporate advanced propulsion technologies…and maintain the existing balanced industrial base. It’s also the only solution that works for all F-35 customers and enables full Block 4 capabilities starting in 2028.”

Tweedie said GE could have an XA100 production model ready for the F-35A and C in 2028—and the engines would integrate “seamlessly” with both aircraft. But making an AETP engine fit the F-35B, which has a unique propulsion system for vertical operations, will require substantially more development work, Tweedie acknowledged. He declined to say how much longer an F-35B-configured engine would take to develop and bring to production. But it can be done, he insisted.

He noted that the F-35A/C and F-35B use different versions of the F135 already; they are “not interchangeable,” although there is some commonality, he said.

The F-35 Joint Program Office asked GE to look at what would be necessary to make the XA100 work with the F-35B’s lift fan, drive shaft and swivel exhaust nozzle, Tweedie said, with emphasis on “how much commonality” and “how much ‘unique’ there would be” between the two versions.

GE was “pleased with the results of the study, in terms of our ability to show a path to make the modifications in a in a B-model derivative that could provide some good capabilities,” he said.

For its part, the JPO agreed “it would be a separate, incremental effort” from the conventional takeoff version, Tweedie continued. “We’ve provided what those incremental costs and timing would be.”

GE gave the JPO and Marine Corps, which operates the F-35B, an estimate of how long a separate AETP engine would take, but Tweedie declined to share it, except that it would be “after” the 2028 target for the conventional takeoff version.

Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall has said the service would like the performance improvements offered by the AETP engines, but USAF would have to bear the development costs alone if the Navy and other partners aren’t interested.

“We certainly perceive a significant amount of enthusiasm from the Air Force leadership … over the last few years,” Tweedie said.

“As you know, [on] December 22, 2020, we fired up the first engine and it worked right, and and that has generated a significant amount of onsite visits from a variety of Air Force leadership, to really ‘kick the tires,’ meet the team, see the … built engine, see [it] … disassembled and just truly understand so that they can make the most informed decision,” he said.

Tweedie argued that a new engine is an operational imperative, given the geopolitical landscape, to power an F-35 with “transformational capabilities.”

Repeating previous claims, Tweedie said the XA100 would provide the F-35A with 30 percent more range increase, 20 percent more thrust, and twice as much thermal management capacity, as well as “durability enhancements and readiness improvements that the warfighter needs.”

“This is a requirements-driven decision process,” Tweedie argued. The U.S. must deal with its pacing challenge in China, and “there’s a timeframe associated with that.”

While “we’re certainly glad to see our competitor”—Pratt—recognize that a new core is necessary, “incremental upgrades to existing engines cannot alone meet the actual needs of the warfighter,” Tweedie insisted.

The Pratt ECU also offers only a seven percent range improvement, he noted.

“It’s not clear that a seven percent increase is something that actually provides operationally meaningful capability to the warfighter,” he said. “So we really feel strongly that the full capability of an AETP solution … is the way to go.”

Also, “injecting competition “into the propulsion world is something that we think can provide a lot of benefits, as has been done on other platforms in the past.”