The U.S. military has worked in space for decades, providing GPS to the masses and bouncing combat messages through satellites to troops around the world. In some ways, though, the Space Force feels like it’s starting from scratch.

The Space Force was created to ward off Chinese anti-satellite weapons and Russian satellites stalking U.S. spy systems across the cosmos, among other concerns. Still, officials are looking for ways to keep space safe and maintain an upper hand while the Pentagon learns how to treat space as it does air, land, and sea.

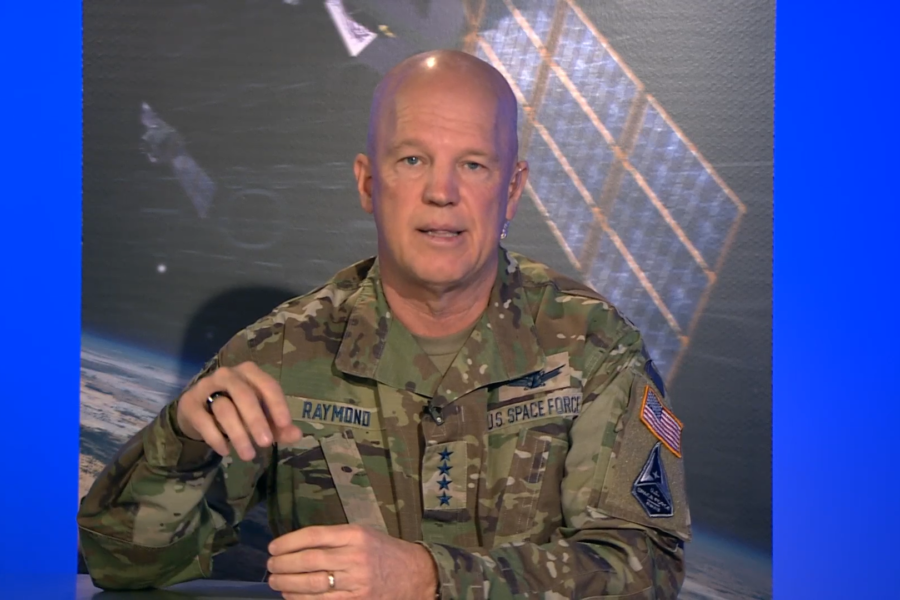

Chief of Space Operations Gen. John W. “Jay” Raymond laid out some of those foundational concerns during a discussion with famed astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson as part of AFA’s Aerospace Warfare Symposium.

Troops need to be able to hold orbital threats at bay, and if they can’t, they need the firepower to respond accordingly, Raymond indicated.

He pointed to World War II, when the Air Force sent 1,000 bombers carrying nine bombs each to hit one ball-bearing factory. Only 100 or so of those 9,000 weapons would explode near the target, he said.

Over time, military aircraft became more precise and powerful, thanks to new weapons and technologies like GPS. But the U.S. doesn’t yet have the means to defend space through force, Raymond said, so the Space Force has to work even harder to maintain a safe status quo.

“If we lost space, do we have 1,000 bombers in our Air Force today? We don’t,” he said. “That’s why I said we can’t afford to lose space, and we’re not going to lose space. It’s too important to us.”

To keep the peace on orbit, the global community is beginning to discuss what norms of good behavior might look like for satellites, other spacecraft, and counter-space weapons. The U.S. hopes established norms and peer pressure may keep other countries—particularly Russia and China—from threatening civil and military assets.

It’s crowded up there, Raymond said, so spacefaring nations should behave themselves.

“I would like my successors to have some rules of the road on how you operate in space,” he said. “It is not safe and professional for Russia to put a threatening satellite in close proximity to a U.S. satellite.”

Creating space safety guidelines won’t solve all of their problems, but will “help identify those that are running the red lights as we drive this car,” he added.

Setting new norms with allies and partners entails getting everyone on the same page about issues like how to respond if a country destroys a satellite, Maj. Gen. DeAnna M. Burt, who runs U.S. Space Command’s Combined Force Space Component Command, recently told Air Force Magazine. Some nations are hesitant to react as strongly in that situation as they might if a human was killed in combat, but the U.S. is urging others to consider the ripple effects of that aggression.

“For many countries, a human has to die for that to be determined as a hostile act,” she said. “If you shoot down a machine, no one died in that instance. But … we now will have second- and third-order effects of more casualties in a given engagement.”

SpaceNews said Feb. 24 the U.S. is drafting language on its position for a United Nations report on “norms, rules, and principles of responsible behaviors” in space. Burt told the publication she wants to see a binding resolution from the U.N. that helps countries hold each other accountable.

It’s harder to call someone “bad or irresponsible if I haven’t fully defined what those things are on the international stage,” Burt told SpaceNews.

A key part of those discussions revolves around discouraging countries from creating exponentially more orbital debris, as the cosmos become home to a growing number of commercial and military satellites, asteroid fragments, and other objects.

The Space Force tracks 27,000 objects on orbit now, while another 500,000 or so are too small to keep an eye on. Nearly 4,000 trackable objects are active satellites—meaning the vast majority of tracked items are space junk that could damage spacecraft in a collision.

One way to curb the spread of space debris is not to create more of it in the first place, Raymond said. That may be a challenge given that companies like SpaceX and the Pentagon itself are planning for thousands more satellites to bolster everything from internet access to hypersonic missile tracking. Stakeholders must also consider engineering solutions to make rocket launches and satellite decommissioning cleaner, for example.

“If you and I could figure out a way to clean up all that debris that’s moving so fast and over those vast distances, let me know and I’ll invest with you, because we’ll be well off,” Raymond told Tyson.