Collaborative Combat Aircraft—the autonomous “wingmen” drones the Air Force is pursuing to pair with manned fighters—can truly provide “affordable mass” because their per-pound cost could be two-thirds or even less than a crewed fighter, experts said last week at AFA’s Air, Space & Cyber Conference.

During a Sept. 18 panel, officials also discussed the reasoning behind the design priorities for CCAs and how they are being developed.

“You buy aircraft by the pound,” noted Robert Winkler, vice president of corporate development and national security programs at Kratos Defense and Security Systems.

Crewed fighters and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) aircraft “normally cost somewhere between $4,000 and $6,000 a pound,” Winkler said. But years of studies from the Air Force Research Laboratory and the Air Force Life Cycle Management Center have led to flying autonomous prototypes with a “baseline now … down to $1,200 a pound for CCA-type equipment, and everybody’s working hard to get even below $1,000 a pound,” Winkler said.

Some companies are even saying they can reduce the price to $600-$800 a pound, Winkler added. “That’s how you get the affordability, at the same time that you get the survivability.”

What is not yet in hand, Winkler warned, are “exquisite” sensors whose price matches the low cost of the airframe.

“The major cost of [CCAs] is going to be mission [equipment],” he asserted. The Air Force’s radars, electro-optical cameras, and ISR equipment are “the best weapons sensors on the planet [but] … what we don’t have is in the middle. We don’t have something that fits, that can be used multiple times, but it’s an exquisite sensor, and we need to get to that part as well; to bring that cost down.”

Survivability—often achieved through stealth—must go hand-in-hand with affordability, Winkler added.

“Obviously, you don’t want to have these aircraft get out there and just get all get shot down. And obviously, you don’t want them to be ‘silver bullets,’ where they cost so much that you can’t afford to lose them. So there is a right balance,” that must be found between those considerations, he said.

CCA drones must have the “right blend of onboard/offboard [mission equipment] and organic survivability treatments and methods such that you have a high probability to get the aircraft back without driving the cost or the ceiling [so high] that you’re afraid to” risk the platform, he said.

“That’s really what we’re after, is affordable mass. So there’s a knee in the curve where that happens. And I think we’ve everything you see on the [exhibition] floor today is pretty much balanced for affordability.”

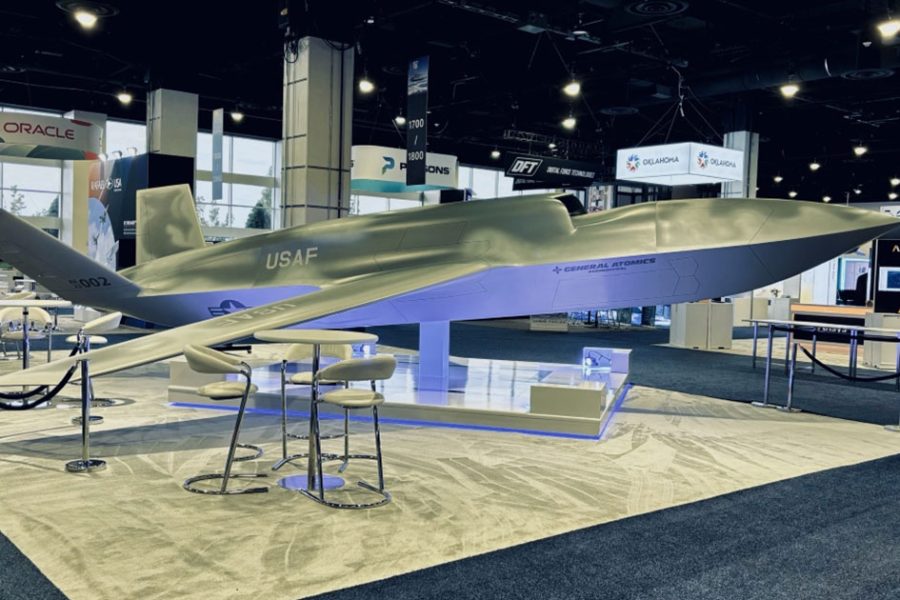

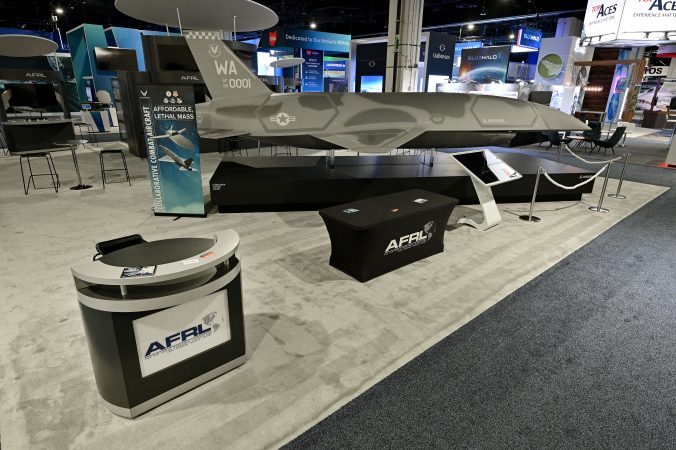

The conference’s technology expo featured full-scale models of Anduril’s “Fury” drone and General Atomics’ unnamed aircraft, which have been selected as the finalists for the first increment of CCA, as well as GA’s actual XQ-67A Off-Board Sensing System (OBSS), which flew last summer and shares many design features with the company’s CCA.

Minimal Maintenance

Beyond mass, CCA drones will also need to fit with the Air Force’s Agile Combat Employment model, operating from remote and austere locations throughout a theater. To that end, General Atomics is aiming to “get rid of any kind of scheduled maintenance,” said Dave Alexander, president of GA’s Aeronautical Systems division.

It will be necessary to put oil and fuel in a CCA. “But other than that, I think we really need to design this system that you don’t touch it out in the field,” Alexander said—minimizing the need for spares and test equipment.

General Atomics has learned from experience with its Predator and Reaper families of remotely-piloted aircraft to “minimize the system. Keep it simple and keep it all-electric,” Alexander said, noting that all-electric aircraft have reduced maintenance needs and higher reliability.

“Let’s design these things so you don’t put wrenches on them … [and with] the minimum equipment list,” Alexander said.

Jason Levin, senior vice president for air dominance and strike at Anduril Industries, agreed with the need to reduce maintenance and added that “the whole point is to reduce manpower and be a force multiplier. We don’t want to add people with the system CCA is delivering. We want to minimize people, minimize infrastructure … autonomy for the whole life cycle; pre-flight, post-flight, maintenance.” That includes minimizing ground equipment and eliminating unique ground equipment when possible.

The goal is to “make the system as easy and intuitive to operate with” and minimize the training needed for operators, he added.

Missions and Testing

Levin also said Increment 1 drones will be constantly improved and updated with what’s learned in perpetual flight testing and software updates. Several members of the panel said that as the CCAs take shape, there’s no substitute for live-fly development of their autonomous brains.

“We have a fleet of surrogate jets we fly at our test sites, so we can take the same autonomy, do the simulation, hundreds of thousands of runs, push it into the jets and fly at our test site,” Levin said. “And we have hundreds of flights of flying these aircraft in multiship formations, doing collaborative autonomy. We’re able to get that feedback early and improve the system over time.”

The main effort for the first increment of CCAs will be rectifying the relatively low internal missile loadout on crewed fifth-generation fighters, according to Maj. Gen. Joseph Kunkel, director of force design, integration, and wargaming.

In the Air Force’s initial analysis of CCA, Kunkel said, the service looked at a wide variety of possible missions—electronic warfare, ISR, suppression of enemy air defenses, etc. Eventually, officials decided that for the first increment, the CCA version that had “the most impact on the battlefield was, frankly, a missile truck; something that could perform the air-to-air mission and be part of this system that produces or achieves air superiority. So that’s why we went with the CCA that we have now,” Kunkel said.

Narrowing the focus for the first increment also met the objective of “to “get something that could have an impact on the battlefield” as quickly as possible, Kunkel said.

Other missions, new weapons, and different kinds of aircraft will be included in other increments, Kunkel added, saying he’s “certain” of it.

Even if CCAs were not “affordable mass,” they would be worth pursuing because they open up new tactical possibilities and allow the Air Force to “take risks we wouldn’t take with something that has a person in it.”

Kunkel noted that an experimental unit has been created at Nellis Air Force Base to put CCA technology in the hands of operators and let them experiment with it to find new possibilities for battlefield use.

“This is not a test unit, this is an operational unit. And the thought is, bring in our warfighters that have some experience with this from all different backgrounds. And not only the flyers that would actually fly and develop tactics, but also folks on the ground, so we can learn exactly what we need from an autonomy perspective.”