When Donna Huneycutt’s company, a woman-owned small business selling professional services to the Air National Guard, got its first really big contract, she made a decision: “We were going to get serious about cybersecurity.”

Following a slew of cyber intrusions by China against defense contractors, the Department of Defense was seeking to shore up cybersecurity standards in the defense industrial base. It was 2018 and an amendment had just come into force to DOD acquisition regulations. Contractors who handled unclassified but still sensitive data known as Controlled Unclassified Information or CUI had to comply with cybersecurity guidelines from the National Institute for Standards and Technology, or NIST.

Although there was no enforcement mechanism in the regulation, Huneycutt said her company WWC Global—which she sold to Command Holdings in 2022—had contracts with Special Operations Command and was doing work that involved access to CUI. So she decided to do the right thing.

“We spent about $1 million, taking into account all the labor hours,” to implement the 110 security controls listed in the NIST document, known as SP 800-171, Huneycutt told Air & Space Forces Magazine.

When they did so, she added, two things happened: “We had to put our prices up, and we found we were being hacked.” Security tools the company installed revealed executives’ phones were being attacked, although the NIST controls helped them identify and block the attacks, she recalled.

Huneycutt has sold her company, but that $1 million investment will finally begin to pay off for the new owners next year, when a long-delayed DOD enforcement mechanism, the Cybersecurity Maturity Model Certification program, or CMMC, starts to show up in DOD contracts. The department rolled out the first version during President Donald Trump’s administration in 2020, but the Biden administration rolled it back the following year for a revamp into two parts. The first part became final last month, and the second part will start to kick in next year.

Huneycutt said she hopes CMMC will help level the playing field for security-conscious contractors. “We were at a disadvantage,” she said of the years after her 2018 decision to get serious about the NIST controls. Her overhead was higher because of the costs of the security measures her company was implementing.

“We were competing with companies who were cheaper because they were less secure,” she said. “If you don’t enforce cybersecurity standards, you create a race to the bottom.”

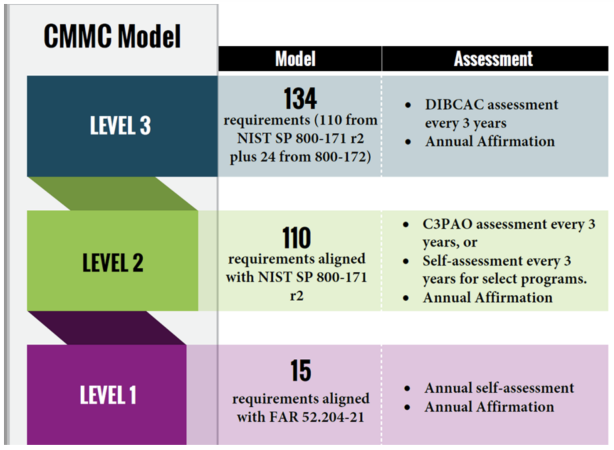

CMMC will require contractors to validate their compliance with the security controls in NIST, albeit at different levels depending on their size and over the course of seven years:

- Just over 103,000 companies will be required to self-attest their compliance with a set of 15 basic security controls for CMMC Level 1.

- 56,000 small businesses will need to get a third-party assessment of their compliance with the 110 NIST controls for CMMC Level 2.

- Fewer than 1,500 businesses of all sizes, whose contracts deal with more sensitive data, will have their compliance with a beefed-up set of 134 security controls assessed by government audit teams under CMMC Level 3.

Huneycutt explained that for companies at Levels 2 and 3, there is a huge administrative burden involved in compliance with the NIST standards. “Every one of those 110 controls had to be written into a company policy,” with personnel to carry it out and a manager assigned responsibility, she said. Everybody had to be trained: “In my business, an hour of somebody’s labor has a dollar value to it. So for every hour that I required for cybersecurity training, that was an hour that I could not ask them to perform and get paid on my time and materials contracts,” she said.

Third-party assessment requires a major record-keeping effort, she added.

”You have to enforce internally, and you have to show that you’ve been enforcing and that you’ve managed situations where people deviated from the policy. All of this requires a tremendous amount of documentation, and therefore a tremendous amount of labor hours, overhead. … It just kind of never ends,” she said.

A wide range of industry associations echoed Huneycutt’s complaints, arguing that meeting the requirements CMMC imposes, depending on how they’re implemented, will impose an unreasonable burden on small businesses and will discourage exactly those contractors that the Air Force and other services want to encourage—small innovative companies at the cutting edge of new technologies.

“DOD itself has acknowledged that it has been hemorrhaging small businesses from the defense industrial base,” said Rachel Gray, the director of research and regulatory policy for the National Small Business Association. She cited DOD statistics that it lost 43 percent of its small business contractors between 2016-2022.

“This is only going to serve to further exacerbate that bleeding,” she said. DOD officials have acknowledged that cybersecurity compliance is a barrier to entry for smaller companies, she said. “We support a secure and strong defense industrial base, but there are ways in which CMMC can be implemented … which will ease the burden for smaller companies, who may not be as well resourced as their larger counterparts.”

ML Mackey is CEO of Beacon Interactive Systems, a small business which is digitizing Air Force flight lines and first became a military supplier through an SBIR contract. She told Air and Space Forces Magazine that, in addition to the cost and the administrative burden, companies could suffer a hit in productivity.

“You might have a commercial email provider and commercial security tools and that might seem—and be—perfectly reasonable to you. But now you might have to move to different providers, ones that are certified to DOD standards,” she said. “It’s like moving house, you still have somewhere to live but the disruption can be considerable.”

Any costs of the transition come out of hide, she said. “Once you’re on a contract, the cost of running your new infrastructure, that becomes part of your overhead cost and it’s allowable—the government will pay it. But that initial piece [buying and transitioning to the new infrastructure and other upfront costs of compliance] is not allowable, so it literally comes out of the pocket of the small business owner,” before they’ve seen the first dollar from a contract, she said.

Huneycutt said providing secure hardware and connections for a single desktop computer costs about $4,000 extra per year, and about $1,500 more for a phone, costs that mount as businesses scale.

CMMC requirements flow down from prime contractors to their subcontractors, so small businesses that are suppliers for large systems integrators have to comply as well.

Mackey said she wasn’t arguing for a free pass: “Industry should pay,” she said.

But depending on how the program is implemented and the burden of compliance is distributed, there might be unintended consequences from CMMC, if it discourages innovative commercial companies from trying to sell to DOD, Mackey explained.

“When all of a sudden we drop a new requirement that has a disproportionate weight on the bottom line of the exact companies whose participation we want to increase; the same companies that we’re having a massive decrease of participation by, then we need to change the model, right?” she said.

“No one is saying small businesses should get a free pass. Everything should be paid for. Business is business. We just need to match [the burden] to the cadence and the abilities of the players that we have on the field,” Mackey said.

She said that there were many ways that novel policy approaches could help square the circle for innovative small businesses.

One suggestion was DOD-provided regional resources—secure workspaces where small businesses can do their work in a CMMC-compliant way without requiring a large upfront investment, for instance on an initial SBIR contract. “They can come in and see what the water’s like, splash around, before they dive into the deep … meaning becoming fully CMMC-compliant,” she said.

She said the U.S. Small Business Administration office of innovation and invention was doing “really interesting work with the [DOD’s] Office of Strategic Capital. They’re looking at existing authorities SBA has for loans and other financial tools and how they can be brought to bear in ways that facilitate participation in the [defense industrial base].”

Mackey said those authorities could also be used to help innovative small businesses meet the upfront costs of CMMC compliance. “The ability to get a line of credit to finance CMMC implementation with an extended payback period, I think, would greatly reduce the barrier to entry.”

Ultimately, defenders of the CMMC say, businesses large and small are going to have to absorb the costs of compliance, because being cyber-secure is just a basic requirement of running a business.

Level 1, the self-attestation to a whittled down set of security controls for 103,000 companies requires “very basic” compliance, Kelley Kiernan, a veteran acquisition professional and now a professor at the Defense Acquisition University, told Air and Space Forces Magazine.

But for the 56,000 companies requiring CMMC Level 2, implementing the NIST security controls needs a professional approach and dedicated cybersecurity personnel, she said. They were “written by cyber engineers for cyber engineers and so you’re going to need a professional on your team [to implement it], and there’s no way around that,” Kiernan said.

“There are charlatans in the marketplace,” she added, warning against easy, off-the shelf, “do-it-yourself” solutions.

“If you needed gallbladder surgery, you wouldn’t do it yourself, you’d find a professional,” Kiernan said, “No one balks at hiring a lawyer or an accountant or a tax professional. Cybersecurity is a critical operating expense.”

“Without robust cybersecurity to protect your intellectual property, you’re not even going to have a business,” she warned, referring to the campaign of cyber-enabled theft of proprietary data and other digital valuables that officials have attributed to China.

“A U.S. small business could implement the NIST standard to protect their IP, even if they did not have a DOD contract,” she said.

“It’s time for small businesses to channel their pioneering insight that got them where they are and embrace their entrepreneurial savvy and change the paradigm to a new truth which says that robust cybersecurity is simply good business in the modern world,” she said, “And the new CMMC program seeks to certify that everybody’s ready to go.”

Editor’s Note: This story was updated Nov. 13 to correct an error in a quote attributed to Kelley Kiernan.