About four dozen companies are gearing up for a technology competition unlike most in the Pentagon as they vie for spots in the Air Force’s Advanced Battle Management System.

ABMS is the Air Force’s multibillion-dollar vision for a massive network of data-processing software, cloud storage, communications hardware, and other tools to connect the force more efficiently. After about two years of planning in earnest, the service is now bringing in a broad collection of defense contractors and commercial companies to fight for a place on that team.

So far, the Air Force has awarded nearly 50 companies seed money as they each look to secure as much as $950 million for their products. Their pitches fall into seven categories: Digital architectures, standards, and concept development; sensor integration; data management; secure processing; connectivity; applications; and integration of platforms and weapons such as smart munitions, attritable aircraft, and electronic warfare.

ABMS has some lofty ideals—reaching across services to connect drone swarms with surveillance data from ships, or using satellite data to aim Army missiles, for instance—but is trying to solve real, persistent problems as well. Famously, the F-22 and F-35 can’t share combat information, emblematic of broader technological and cultural silos that keep useful information from service members that would help them plan next steps.

The venture has its critics, who say ABMS is still a patchwork of ideas without a true strategy for how to make disparate systems talk and how to show commanders a menu of combat options. But conversations with the competitors offer a clearer picture of how the network might come together with artificial intelligence algorithms, data visualization interfaces, far-reaching radios, and more.

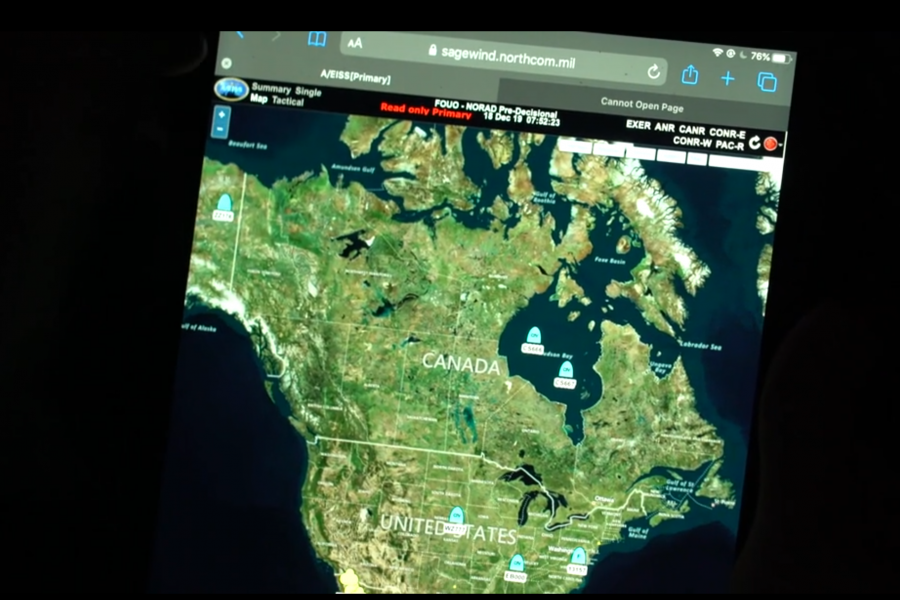

Some companies will participate in the second demonstration of these network possibilities next month, while others say they aren’t sure how the Air Force envisions using their products. The upcoming demo will simulate an attack on U.S. space assets and the homeland, and is expected to traverse greater distances and connect more bases and weapon systems than the first exercise in December 2019. Nellis Air Force Base, Nev., will host the event.

Andy Narusewicz, head of Defense Department programs at Los Angeles-based Silvus Technologies, hopes the second demonstration pushes the boundaries more than the first round. While the first event was largely successful, he wants to see whether military networking can scale up to connect across states at once—a sign of whether the concept would work in real-life global operations. He also hopes to share information across multiple frequencies and hundreds of miles using Silvus’s wireless radios, and to learn more about how much data the military can pass back and forth without breaking the network.

The second demo could feature live-fire exercises to which the military would respond, as well as new ways of collecting and sharing intelligence. Narusewicz also noted the demonstration will try to quickly set up a remote base and enable it to communicate back with a command center and other forces.

In contrast with many major military ventures that stick with the traditional defense industrial base, ABMS is bringing together well-known Silicon Valley names such as big-data firm Palantir Technologies, tiny startups like SimpleSense, and defense mainstays such as Lockheed Martin and BAE Systems. Some are tapped for all seven lines of effort within ABMS, and others are playing in just one category.

The products, with names such as VENOM, UNICORN, and PLASMA, aim to make up the common operating picture that shows the Air Force what’s going on around the world and how to handle it. Those tools can automate and display everything from aircraft tasking orders to target tracking.

PLASMA, or the Platform for Leveraging Analytics for Streaming Multi-Intelligence Awareness, is an analytics platform that lets users set up data-analysis processes without knowing a particular programming language. The tool then automatically crunches and shares that information, according to the company Strategic Mission Elements.

The company says it is waiting to hear whether the Air Force is interested in its Visual Explanation and Narration of Models, or VENOM, system. VENOM offers 23 different data visualization widgets to help predict future trends in fields like intelligence.

Canadian-run firm CAE’s U.S. branch is pitching its own modeling prowess with wargame simulation technology, dubbed Dragonfly, that uses AI to present multiple courses of action for the military to consider.

“CAE’s system of systems will have a 360-degree compound-eye vision of the world, wired to react rapidly to targets, threats, and events,” the company said. “This development is expanding CAE’s existing synthetic environment expertise into space, allowing users to track and inspect existing satellites as well as use modeling and simulation to generate new satellites, theoretical satellite orbits, conjunctions, breakups, and other interactions.”

CAE technology will also let the military game out electromagnetic and cyber operations.

Another participant, Cubic Corp., is offering full-motion video processing and sharing services so users around the globe can act on those images in real time. It also has radio frequency devices and sensors that can get around network jamming and security problems on the electromagnetic spectrum.

Yet others are more concerned with the pathways along which that data travels.

“NETSCOUT will bring their [network traffic analysis] expertise and solutions to the ABMS architecture to allow the Air Force to measure the quality of the services and the networks that will be connected,” a company spokeswoman said. “The technology we bring is fully developed and currently deployed throughout the DOD.”

Some offered their own ideas for how the Pentagon can test its command-and-control vision.

“SAIC proposes an experiment that will pave the way for future requirements such as distributed cluster computing and swarm capabilities,” said Vincent DiFronzo, the company’s senior vice president focused on Air Force and joint DOD commands.

Many of the companies have worked with the Defense Department before. Some warn of the pitfalls of doing business with the military, like spending extra money to build technology from scratch when a viable option is already available. Others say they’re optimistic that the Air Force is encouraging companies to collaborate instead of beating each other out.

SimpleSense offers tools to connect Air Force security forces with local emergency responders to ensure the military is aware of what’s happening nearby and to react faster—for example, if a burning car is sitting outside a base’s gate, or if a service member’s off-base home is on fire. That same approach to data-sharing can benefit ABMS, SimpleSense CEO Eric Kanagy said.

“The companies that succeed in the next decade will be the ones to bridge existing platforms,” he said. “The problem today is not that there’s not enough data—there’s too much, in too many systems and platforms. By connecting isolated sets of data, the data as a whole becomes exponentially more valuable.”