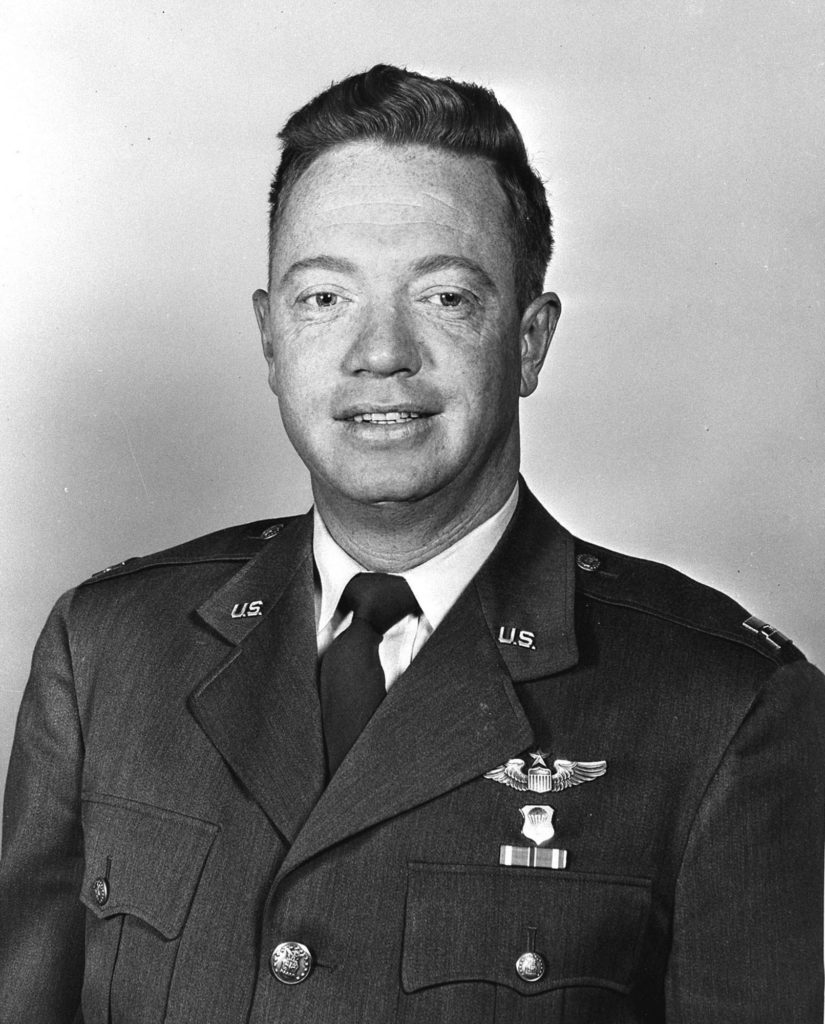

Col. Joseph W. Kittinger, Jr., a Vietnam-era fighter pilot, prisoner of war, and recipient of the Harmon Trophy whose freefall jump records earned him a place in the National Aviation Hall of Fame, died Dec. 9 at the age of 94.

Kittinger, who was also awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and two Silver Star medals, was most widely known for Project Excelsior, a series of freefall jumps from research balloons that he made to both test the effects of high altitude on the human body and to improve the safety of pilots ejecting from aircraft at very high altitudes.

His records stood for 52 years until 2012, when he helped daredevil Felix Baumgartner break most of them.

Kittinger was born in Tampa, Fla., in July 1928. He entered the Air Force through the aviation cadet program at age 21, earning his wings in 1950. He flew P-51 fighters in Germany until 1953, when he joined the Air Force Missile Development Center. There he flew experimental aircraft and conducted aeromedical research. He made the switch because of the allure of more flying time and potential “adventure,” he later told an interviewer.

Among his activities at the center, Kittinger flew zero-gravity missions and flew “chase” for high-speed rocket sled runs made by fellow researcher John Stapp.

He joined Projects Man High and Mile High to study the effects of cosmic radiation on human physiology in preparation for U.S. manned space missions. As the pilot of a balloon dubbed “Mile High One,” Kittinger achieved an altitude of 96,000 feet, about a quarter of the way to outer space. For this work, he received the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Project Excelsior, which ran from 1959 to 1960, was meant to study the ability of a human being to survive an extremely-high altitude ejection. Kittinger, in a space suit, jumped from Excelsior I, II and III, from 76,000 feet, 74,000 and 102,800 feet, respectively—the last being about 20 miles above the surface of the Earth. The Excelsior I mission was disastrous and nearly killed him, as the drogue line wrapped around his body and he blacked out from spinning in descent, enduring 22Gs. He was saved by an automatic back-up chute.

On the final record ascent, he discovered that his right glove had not been properly pressurized, and he told Air & Space Forces Magazine in 2014 that his hand had “doubled in size” due to the low atmospheric pressure. He also nearly suffocated, as his air hose pushed against the helmet neck midway through the ascent but became freed near the apex of the flight. The ambient temperature at the time of his jump was -94 degrees Fahrenheit.

On the last mission, he set records for highest balloon ascent, longest parachute freefall—about 16 miles—and fastest speed by a human moving through the atmosphere without an aircraft: 614 miles per hour.

The missions were also meant to test improved parachute design for ejections in atmospheric regions of low air density and at high velocity.

“One of the objectives,” Kittinger told an interviewer in 2014, “was to devise a means of escape from very high altitude.” Reserarch and experience had shown that pilots ejecting at high altitude or extreme speed went into dangerous spins. He said the drogue chute design resulting from the research “is still in use today; every ejection seat has it. That makes me and my team very proud because we made a contribution.”

A photo of Kittinger, automatically taken after he made his record jump, was featured on the cover of Life Magazine. He also appeared on TV on “The Ed Sullivan Show” and “What’s My Line,” discussing his exploits.

In 1960, Kittinger received the Harmon Trophy directly from President Dwight Eisenhower for “outstanding accomplishments in aeronautics.” His final high-altitude balloon flight was with Project Stargazer in 1962, in which he explored the feasibility of performing astronomical research from high-altitude balloons as part of a two-man crew.

Returning to the combat air forces in 1963, Kittinger deployed to Vietnam, where he flew the A-26 Invader for two tours. After a stint as a fighter pilot with US Air Forces, Europe in Germany, he returned to Southeast Asia in 1971, flying F-4 Phantoms out of Udorn Royal Thai Air Force Base. He commanded the 555th Fighter Squadron.

Kittinger shot down a MiG-21 in combat on March 1, 1972, engaging a “superior number of enemy aircraft” which were attacking friendly ground forces, according to his Silver Star commendation. Two months later, however, he was shot down, along with his backseater, 1st Lt. William Reich, and taken prisoner.

He spent 321 days as a POW in the infamous “Hanoi Hilton,” enduring repeated torture and serving for a time as the commander of the prisoners. Kittinger became skilled at catching rats for additional protein and led the other prisoners in defiant religious services and exercises. He was repatriated in 1973 after the Paris Peace Accords, as part of Operation Homecoming.

“We never doubted we would get released,” Kittinger said in 2014. “It made us better Americans, to appreciate what we had. Being a POW was life-changing.” He received a second Silver Star for his heroism as a POW.

Returning to duty, he attended the Air War College and then served as a Vice Wing Commander in USAFE. He retired from the Air Force as a Colonel in July, 1978, with 29 years of service, having accrued more than 7,600 flying hours and 483 combat missions.

Kittinger continued to fly aircraft and balloons in retirement, accumulating a further 9,100-plus flying hours. In September 1984, he became the first person to make a solo crossing of the Atlantic Ocean in a helium balloon, flying from Maine to Italy, where making a crash landing, he broke his foot. That year, he was elected to the National Aviation Hall of Fame.

At the time, he told U.S. News and World Report: “Life is an adventure, and I’m an adventurer. You just have to go for it. That is the American way.”

In 2008, he received the National Air and Space Museum Award for his lifetime of achievements.

After turning down requests for assistance from many seeking to break his parachuting records—because they were either not prepared for the attempt or not able to make the requisite investment in equipment—Kittinger agreed to help Felix Baumgartner of Red Bull fame. Besides consulting on the design of the 2012 attempt, Kittinger served as the “capsule communicator” for Baumgartner, talking him through the ascent in the gondola and ensuing 24-mile jump, during which Baumgartner exceeded the speed of sound, traveling at 833.9 mph.

Although Baumgartner fell a greater distance than Kittinger, he popped his parachute a few seconds shy of Kittinger’s freefall record, which still stands.

Joe Kittinger Park in Orlando, Fla. is named for him; it is decorated with an F-4 on a pole that is painted as Kittinger’s aircraft in Vietnam.

He published an autobiography in 2011, “Come Up and Get Me,” co-authored with Craig Ryan. The book’s forward was written by Apollo moonwalker Neil Armstrong.