VANDENBERG AIR FORCE BASE, Calif.—Col. Scott Brodeur has big plans for the Combined Space Operations Center here as he enters his last few months as commander.

The CSpOC is a secretive command-and-control organization that tracks objects in space and acts as a liaison between those who operate military space assets and those who need their services. But Brodeur wants to make the center’s work truer to its name.

He is leaving the CSpOC this summer to run the National Space Defense Center, the Colorado-based counterpart that focuses on defending satellites and other assets from harm. The colonel is only planting the seeds for a better CSpOC now, and is just one voice in a fledgling service charting its future day by day. But if his plan succeeds, it could outlast him to shape international military space cooperation for decades.

The CSpOC was formed out of the Joint Space Operations Center in July 2018, evolving from a multiservice group that focused solely on using space assets to support combat operations. Now-Space Force boss Gen. Jay Raymond proposed the CSpOC become a new kind of center. It would continue the old mission, but while building closer partnerships with commercial companies, academia, civilian agencies, and strengthening outreach to other countries.

For being an international hub, Brodeur found when he took command in June 2018 that the CSpOC wasn’t talking to the outside world much. The center needed to alert its coalition partners about an issue that was happening, and Brodeur wanted to call the space ops centers in the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada.

“People are fishing around with papers and are like, ‘What’s the number?’” Brodeur told Air Force Magazine in a recent interview. “I was like, ‘Do we not contact them like every day?’”

The answer was no. The partners sometimes planned future work together, and strategy experts conferred in periodic meetings. U.S. Strategic Command, which until recently oversaw military involvement in space, also facilitated those discussions.

“There was not a day-to-day thing,” Brodeur said.

He immediately instituted phone calls at every shift change to discuss intelligence, situation reports, requests from forces for space support, and more.

“That has grown into numerous engagements of bringing our partners here for education, immersion, and dinner,” Brodeur said. “We send people out to their operations centers, so that now we’ve actually built a relationship where there isn’t a shift that goes by where we haven’t talked to the partners, which is pretty cool. But that wasn’t the case when we became the CSpOC.”

Another milestone on the path to closer international collaboration involves Operation Olympic Defender. Created in 2013, it is the overarching effort to deter hostile actions in space, just as Operation Inherent Resolve serves as the campaign against the Islamic State group. The CSpOC largely handles warning and assessment duties and space support to warfighters under Olympic Defender.

They’re busy: in 2019, the center received 764 requests for space support from forces overseas—a 400 percent increase over the previous year. It tracked 762 missile launches around the globe; sent notifications 105 times to tell someone an adversary satellite had moved (and tracked 340 foreign satellite maneuvers); resolved satellite communications signal interference 189 times; and built about 11,000 space weather reports.

“It’s supporting a carrier strike group in the Sea of Japan. It’s … monitoring the communications, or looking at electromagnetic interference on a bomber mission that may be dropping munitions in Syria,” Brodeur said.

“If we do a show of force, I might be looking at an adversary airfield for aircraft taking off using [Overhead Persistent Infrared],” he added. “I may be monitoring special communications for special ops doing a tasking mission in Yemen. We support humanitarian assistance. We do thousands of space weather reports and custom reports for customers, and then we support a whole host of exercises.”

Then-STRATCOM boss Gen. John Hyten opened Olympic Defender to America’s four “Five Eyes” partners—the UK, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand—plus France and Germany in December 2018. The order allowed the coalition to create a multinational space force that is still evolving today.

“We’ve offered their input into an annex to that order that says, ‘Here’s the capability, the people, our interests, our priorities that we’re presenting, and maybe there’s some stuff we’re not, and here’s my red lines … and what I won’t do,” Brodeur said. “The UK and Canada have officially come back with their annexes and said, ‘I join.’”

Australia has done the work to join Olympic Defender but had not formally declared its intent to do so, Brodeur said Feb. 6.

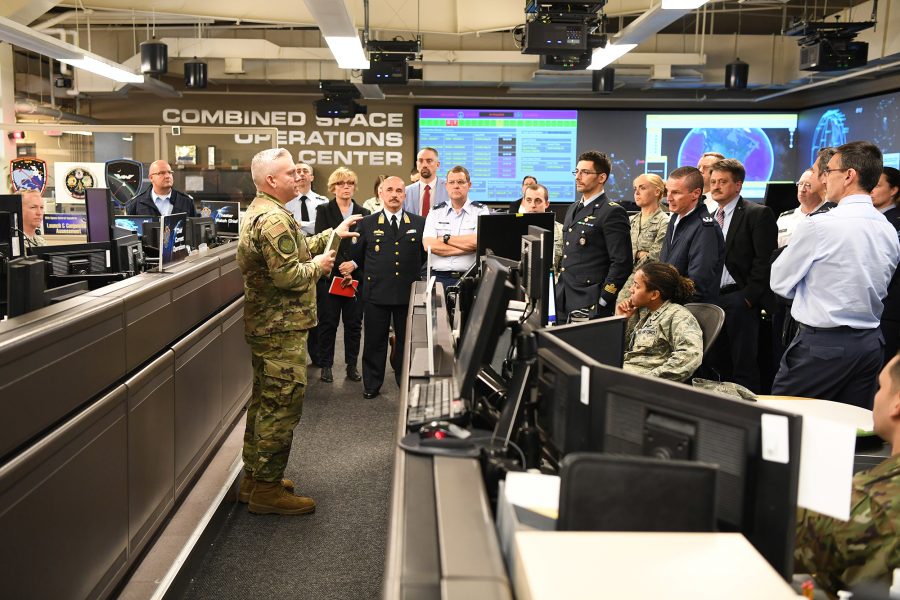

The CSpOC hosts two types of foreign personnel: Five Eyes exchange officers, who work on the ops floor here while an American counterpart goes to the other country, and other nations’ liaison officers, who provide input on behalf of their own country but don’t have a seat on the floor. The center also has information-sharing agreements with 25 countries and at least 75 companies.

About half of the 13 crew positions on the floor are filled by coalition personnel, while some jobs are still too classified for them to do. The CSpOC also hosts a growing Mission Defense Team that scans space systems for vulnerabilities and fixes any that pop up.

Brodeur said he expects new partnerships with countries like Japan, Italy, and “maybe even South Korea,” in the near future, and the center could be getting a new liaison relationship this year. Those people could initially have a more limited role through the multinational space collaboration office, but eventually will be allowed to plug into regular operations.

Once a country signs up for Olympic Defender, Brodeur wants everyone to see the same information. The Space Force is pursuing a new ops floor for space domain awareness that would connect counterparts all over the world with a common picture of what’s happening on orbit. CSpOC personnel hope to be up and running in a new facility across campus at Vandenberg by the end of the year, though prohibitive policies can take longer to untangle.

If successful, for example, a German space situational awareness officer could tap into Germany’s SSA Center from the U.S., and a French officer could do the same for a new SSA facility under construction in France. That work would make the combined force more aware of what’s happening to foreign and domestic space assets and more responsive to any issues that arise, instead of having those officers simply advise the U.S.

“No one is doing this type of integration in space anywhere else, and the only place it’s going to be is here, and to be able to take … an administrative liaison relationship with these partners and being able to give them an operational environment where they can now communicate and work through the actual architectural and communications issues, is a complete game-changer,” Brodeur said.

That doesn’t happen now because militaries are still figuring out how to share information with people who might not have the right security clearance level, but should still be in the loop. Royal Canadian Air Force Maj. Michael Lang, an exchange member at the CSpOC, told Air Force Magazine there’s been a huge improvement over the past decade, but collaboration still isn’t as fast as he’d like it to be.

Brodeur wants a more comprehensive space domain awareness screen that shows support to the entire globe at once, instead of separately looking at areas like the Middle East and Indo-Pacific.

The CSpOC will see other changes as well. Brodeur expects the defense-focused part of Space Force will take on more of the center’s command-and-control responsibilities in the future. Partnerships with commercial companies will grow and diversify. The center could get a training system so people can take risks and make mistakes without fearing the real-world consequences. And Brodeur wants to fill his empty billets.

“We’re not fully manned … and we struggle with the budget shortfalls. But mission-wise, we’re still able to carry on,” he said. “How we present some forces to geographic combatant commands is going to cost money, and I know that even if we had all of our billets funded, we’re still working on the people and the education and the [military construction funding] to build the ops centers and the headquarters.”