Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III told lawmakers North Korea’s weapon supply bolstered Russia in its war with Ukraine, part of a broader coalition that has aided Moscow’s efforts including Iran and China.

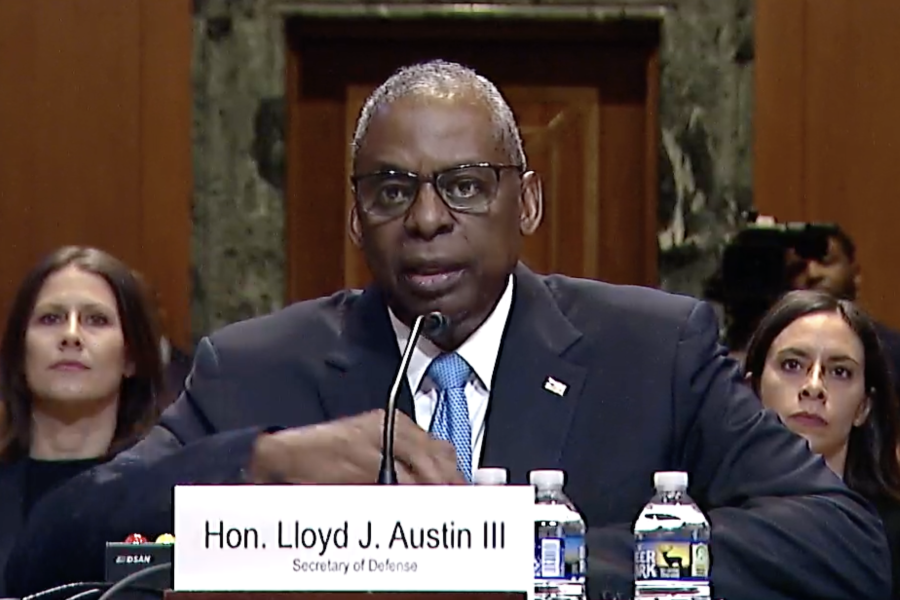

“We saw Russia engage North Korea, who provided quite a bit of munitions and missiles, and the drones provided by Iran really helped to begin turning the tide there for Russia a bit, and allowed them to get back up on their feet, in addition to them increasing their production in their industrial base,” Austin told the Senate Appropriations defense subcommittee on May 8.

The White House reported that North Korean-produced ballistic missiles were fired into Ukraine from Russia in January. The following month, it disclosed that since September 2023, North Korea had delivered more than 10,000 containers of munitions to Russia. Experts have noted that arms sales likely began in 2022 during the initial stages of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“Without the help from Iran, North Korea, and China, this probably would not have occurred to the degree that it has occurred,” Austin said, referring to the current scale of the prolonged war.

Recent findings have cast doubt on how effective these weapons are. On May 7, Kyiv’s top prosecutor told Reuters nearly half of the Pyongyang-made missiles fired at Ukraine by Russia between December and February “lost their programmed trajectories and exploded in the air.” Experts note this isn’t surprising, given Pyongyang’s outdated weapon production skills and some of their stocks dating back to the Cold War era.

However, it does pose concerns for the U.S. and its allies, as North Korea can effectively “test” its missiles in Ukraine, which could lead them to enhance munition production and provide better arms to Russia and others in a few years.

“North Koreans can learn about how effective their weapons are,” Andrew Yeo, senior fellow at the Brookings Institute, told Air & Space Forces Magazine. “I can’t say these improvements will be made immediately, but I would say over the course of a year or two, that they could make improvements to their missiles.”

Yeo added that for Russia, simply having more missiles in their arsenal is crucial at the current war stage. And the longer the conflict goes on, the more opportunities for North Koreans have to enhance their production capabilities.

In exchange for missiles, Russia is believed to be giving North Korea economic aid and military technology. This could also could extend to the exchange of military equipment.

“The question is if Russia would help them with industrial production and provide them with weapon parts or components,” said Yeo. “These all violate sanctions, but it seems clear Russia doesn’t care too much about upholding international sanctions.”

Austin said that the Pentagon is being “as effective as we can” by being engaged in the right channels to meet these challenges through sanctions. But he added that the effort “continues to be a work in progress.”

Yeo said sanctions remain a vital tool for slowing production.

“It makes some companies and individuals think twice if they want to do business with North Korea,” said Yeo. “We don’t know how much more would be entering and exiting North Korea if sanctions were completely removed, so there’s still some impact of having sanctions. But because much of the trade in resources like energy is coming from Russia and China, and the big players aren’t enforcing them, they are just not as effective.”

According to Yeo, the continuous illicit arms trade is a lifeline for “cash-strapped” North Korea. With demand rising from conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza, the regime profits from selling ballistic missiles, small arms, and other weapons. The revenue then funds its missile, space, cyber, and nuclear programs.