CCAs Could Make Up 1/3 of Combat Air Forces

By John A. Tirpak

The Air Force could field 1,000 or more autonomous Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) in the next decade or so, uncrewed, semi-autonomous aircraft that would accompany F-35s and future Next Generation Air Dominance aircraft into battle, Secretary Frank Kendall announced at the 2023 AFA Warfare Symposium in Denver.

The 1,000 CCAs are a planning figure, not a program of record. Kendall said the figure is based on the idea that two CCAs would partner with each of 300 F-35s and 200 NGAD aircraft.

The plan answers the Air Force’s need to build up its combat fleet at a lower cost than the $80-million-per-copy cost of an F-35A, while at the same time not exacerbating the service’s chronic shortage of pilots. Kendall asserts that CCAs should also enhance the effectiveness of crewed airplanes, particularly in lethal contested airspace.

Kendall’s mention of 200 NGADs, though “notional,” marked the first time a USAF leader offered any number for how large that fleet could be. Significantly, it is greater than the number of F-22s the Air Force acquired, even though service officials have previously said they do not plan to replace the F-22 on a one-for-one basis.

At a cost of $80 million to $100 million or more, the high cost of new fighter aircraft are among the drivers for developing CCAs, Kendall said. NGAD will cost “multiples” of what the F-35 cost today, he said.

Air Force Secretary Frank KendallWe’ve got a lot to learn, and that is going to take some experimentation … some testing and some careful thought.

Relying only on manned fighters alone would yield “an unaffordable Air Force,” Kendall asserted. He said he is now satisfied that the technology is at hand to allow CCAs to do what the Air Force needs them to do, “on a timetable” that meshes with strategic demands. He did not specify an in-service date for the first examples but has previously suggested that 2030 is a likely target.

When the Pentagon unveiled the 2024 defense budget request days later, it expanded on his comments, stating: “Investing in this mix of aircraft provides an opportunity to increase the resiliency and flexibility of the fleet to meet future threats, while reducing operating costs.” One reason CCAs should cost less: They don’t have to carry a pilot’s weight or any of the extensive life-support systems, from oxygen to ejector seats, needed in crewed aircraft.

Kendall said the Air Force is requesting “the resources needed to move these programs forward along with associated risk-reduction activities that will allow us to explore operational, organizational and support concepts, as well as reduce technical risk.”

In a press conference, Kendall said his estimate of 300 F-35s that might operate with CCAs is “somewhat arbitrary, [but] a reasonable starting point” for analysis. Not all F-35As will necessarily operate with CCAs. The Air Force already has well in excess of 300 F-35As, and has never officially deviated from its 20-year-old requirement for 1,763 Lightning IIs.

Kendall’s objective is for CCAs to cost less than half the price of an F-35. At that rate, a fleet of 1,000 CCAs would cost upward of $40 billion.

Still, the 1,000 figure “isn’t an inventory objective, but a planning assumption to use for analysis of things such as basing, organizational structures, training, range requirements, and sustainment concepts,” Kendall said.

Asked the ultimate inventory goal for CCAs, Kendall answered, “I don’t know,” and allowed that “it could be more” than the 1,000. The planning figure gives Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr. “a reasonable assumption,” he said, “a basis to begin some planning.”

Kendall added that the number of CCAs should not affect the numbers “of the crewed fighter inventory.” But in time, as the technology is proven, that is unlikely to remain the case.

Initially, CCAs can be thought of as “remotely controlled versions of the targeting pods, electronic warfare pods, or weapons now carried under the wings of our crewed aircraft,” Kendall said. These new systems “will dramatically improve the performance of our crewed aircraft and significantly reduce the risk to our pilots,” he added.

Air Force planners have said that as many as five CCAs could collaborate with each crewed fighter, filling roles in electronic warfare, suppression of enemy air defenses, sensing, communications, and even as weapons carriers. In Denver, Kendall did not narrow down what roles the notional two CCAs per fighter would undertake.

“We’ve got a lot to learn, and that’s going to take some experimentation … some testing and some careful thought,” Kendall noted. His 1,000 CCA planning figure “is a reasonable first tranche,” he added, and deploying them at the rate of two CCAs per crewed fighter is “a reasonable ratio—we’ll learn as we go.”

Ultimately, Kendall and others are seeking the “sweet spot” in the crewed-uncrewed ratio. “We don’t want to undershoot [or] … overshoot,” Kendall said. Overshooting would create “a problem program that gets caught in schedule and cost overruns,” while undershooting could leave the Air Force short of needed capabilities. “I want to push the technology without pushing it too far.”

Maj. Gen. Scott R. Jobe, Air Combat Command’s director of plans, programs and requirements, said in a panel discussion that the notion that these new CCAs would be “attritable” is a “common misconception.” He said the CCAs will be valuable weapons, expected to deploy for missions and return to base for future flights like any other aircraft.

The idea of expendable CCAs is a holdover from the last administration, when former USAF acquisition executive William Roper argued for a generation of aircraft that would be used for 5 to 8 years, then retired or sent on one-way missions in battle. The savings from designing the aircraft for long-term sustainment would be funneled into subsequent iterations of CCAs.

Under Kendall’s vision, the Air Force is focusing on CCAs that will operate alongside crewed fighters for somewhat longer. Using them as kamikazes would be up to the battle commander, he said, but they won’t be built with that purpose in mind.

“We’re going to reuse these air vehicles,” Jobe said. They must be “affordable assets. … We’ve got to make sure that everyone keeps an eye on that.”

Jobe said the Air Force is “still working out” the desired service life for CCAs. While squadrons will operate with CCAs daily, he suggested savings could be found in not flying all CCAs “until we unpack them” for combat missions.

Gen. Mark D. Kelly, who will retire this year as head of Air Combat Command, was cautious in his view of what today’s pilots can manage when it comes to flying their jets as well as CCAs. Two CCAs per fighter might be too much to aim for right away—saying he would prefer starting with one and “see where it takes us.”

Kelly said fighter pilots will need time to get used to working with CCAs in order to trust them to do what they’re supposed to without getting in their way.

“A lot of discovery” needs to happen still, Kelly told reporters during the conference. Once it’s proven that CCA can perform missions like “sensing or jamming, or something like that,” then a second aircraft could be added to perform a different mission, he suggested. Kelly said he “could see” as many as three CCAs per crewed fighter, as long as they don’t impose undue burden on the pilots who must control and direct them.

All this will take years, Kelly said. Meanwhile, the FAA and other government agencies will have to approve their use to transit commercial airspace. The Air Force risks getting ahead of itself and investing in technology it can’t employ if it isn’t careful, he warned. Another unproven capability, Kelly added: “Well before you get to weapons employment, you’ve got to get to the ability for [CCAs] to do auto-target recognition,” he said.

Advocating an iterative approach to CCAs, Kelly said the Air Force must ensure it brings RQ-4 operators, MQ-9 Reaper pilots, and RC-135 Rivet Joint electronic warfare operators into “the room” as details, processes, and requirements are worked out. Those operators “know how to handle lost links” and other potential problems that CCAs will inevitably face. The Rivet Joint operators are skilled in the “high-end jamming and SIGINT,” or Signals Intelligence, missions he thinks CCAs will take on.

Kendall said the Air Force will ask Congress to fund CCA stand-ins that are “not the ultimate” version of what’s needed, but “which we can use for a variety of things: to develop operational concepts, to develop technology, reduce the risk of the program … and start to think through some things, like how we train.”

The Air Force has been experimenting with autonomous, uncrewed aircraft like the Kratos XQ-58 Valkyrie and General Atomics’ Avenger for several years, developing autonomous flight programs like the Skyborg, and trying out crewed/uncrewed teaming concepts.

There are many useful CCA concepts already circulating in industry, Kendall said, and given that there are “a lot of candidates,” the program will be highly competitive, which in turn should drive costs lower.

Jobe said the concept of CCAs is to achieve “overmatch” of an adversary, not only in technology, but potentially in numbers.

Brig. Gen. Dale White, Program Executive Officer for fighters and advanced aircraft, said cost will be a key parameter of the new autonomous aircraft, but hardly the only factor. “We need … affordability and capability,” he said. “No matter how cheap it is,” if the CCA isn’t capable enough to send into the fight, it won’t be worthwhile.

Mike Benitez, director of product at Sheild AI, which has an agreement to develop CCA technology with Boeing, said the Air Force must constrain the manpower demands for supporting CCAs. Today’s uncrewed aircraft have a manpower requirement “four to five times” that of crewed aircraft, which is not sustainable in an Air Force where people are the most expensive asset and recruiting remains an ongoing challenge.

Benitez said the Air Force must also establish a CCA industrial base capable of producing new aircraft fast enough to replace CCAs lost to combat attrition. It must aim for “capable mass at scale,” he advised.

Kendall said he’s confident in the CCA technology, but concerned that delays and fights in Congress risk setting back the Air Force. He pleaded for timely authorization and appropriation bills, before the end of the fiscal year.

Continuing resolutions (CRs) have become routine, occurring in 12 of the past 13 years. New programs can’t launch under CRs, however, and the risk of a year-long CR could be enormous. It would waste time the Air Force doesn’t have to spare, Kendall said.

“My greatest fear” is that Congress won’t quickly enact the next defense budget, he said. Such delay would be “a gift to China … that we cannot afford.”

Saltzman’s ‘Theory of Competitive Endurance’

By Greg Hadley

AURORA, Colo.

The Space Force is doubling down on its warfighting focus under new Chief of Space Operations Gen. B. Chance Saltzman. At the AFA Warfare Symposium in March, Saltzman pressed to sharpen the Space Force’s doctrine, strategic direction, and operational concepts. He laid out a new “working theory of success” centered on long-term competition with space powers such as China and Russia, which he dubbed “Competitive Endurance.”

“I intend Competitive Endurance to be a starting point for a dialogue I believe is critical—absolutely critical—to the success of our young service,” Saltzman said. “The goal of this theory of success is to … deter a crisis or conflict from extending into space and, if necessary, allow the joint force to achieve space superiority, while also maintaining the safety, security, and long-term sustainability of the space domain.”

Chief of Space Operations Gen. B. Chance SaltzmanThe Space Force must shift this balance by making an attack on satellites impractical and self-defeating.

Competitive Endurance is undergirded by three core tenets, Saltzman said:

- “Comprehensive and actionable” domain awareness to ensure the Space Force is never operationally surprised;

- Overall “first-mover advantage” to ensure no adversary can overcome the resilience of U.S. Space Force satellite architectures; and

- Counterspace capabilities to deter adversaries from risking conflict in space, while always acting responsibly in orbit.

Saltzman never mentioned China by name, but there was little doubt the adversary he had in mind when he warned that “our competitors watched, plotted, and invested in capabilities to blunt our advantages in space.”

“The rise of these threats against on-orbit systems and increasing threats to the joint force from adversary satellites drove us to the realization that we must be able to contest and, when necessary, control the space domain,” Saltzman said.

Brig. Gen. Anthony J. Mastalir, commander of the new U.S. Space Forces Indo-Pacific component, defined that threat even more explicitly:

“The [Peoples Republic of China] has put out a lot of satellites just within the last five to six years,” Mastalir said. “There’s a lot of capability on most of those—many of those are intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance satellites designed to find, fix, track, and target U.S. forces and allied forces. They’re designed to help kill Sailors, Airmen, Soldiers, and Marines.”

Saltzman also warned about the rapid number of “dramatic offensive capabilities” the Chinese have deployed recently.

“The thing that concerns me the most is the pace with which they made their shift to a very operational aggressive counterspace capability,” Saltzman stated. “And I’ve been doing this a long time. In 2007, when they launched the [anti-satellite] missile … we knew this was different. Like, OK, this is not normal anymore. Things are going to be different. …

“Now it’s going on 16 years later, and they’ve put some remarkable capabilities on orbit and on the ground to really affect the advantages we have,” Saltzman continued. “It’s a pretty remarkable shift, if you think about how fast they put all that together.”

Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall’s oft-repeated focus on China has frequently been viewed by some as all about Air Force capabilities, but it’s clear he believes the Space Force also has significant work to do to ensure it is ready for competition and, if necessary, conflict.

Maj. Gen. Gregory J. Gagnon, deputy Chief of Space Operations for intelligence, added: “Space superiority will have to be gained in a conflict in the Pacific against the PLA. Their on-orbit armada of satellites can track us, can sense us, can see us, can connect that data … and can now hold U.S. forces at risk in a way we have never understood or had to face to date. And that is what has been the fundamental change in force design.”

Resilience in Many Ways

As things currently stand in the space domain, Saltzman said, the U.S. is so dependent on its space capabilities to fight and operate on the ground, at sea, and in the air, that China or another adversary is actually incentivized to try to take that advantage away, to go on the offensive first.

“This is an unstable condition that works against deterring attacks on space assets,” Saltzman said. “We can’t have that.”

Lt. Gen. DeAnna M. Burt, deputy Chief of Space Operations for operations, cyber, and nuclear, said that China is just as much a focus for the space operators. “We’ve talked about China, China, China, and why we need that resilient architecture in order to continue to fight through that,” she said. “We’ve focused on how the U.S. and allies … [can] continue to provide that capability through all stages of conflict.”

Current space capabilities were built for a different era, when space was viewed as benign, and the greatest threats were meteors or space debris. Now, those threats have multiplied.

“The Space Force must shift this balance by making an attack on satellites impractical and self-defeating,” Saltzman said. This, he argues, would discourage adversaries “from taking such actions in the first place.”

No wonder, then, that the first of Kendall’s seven Operational Imperatives is an “operationally resilient space order of battle.”

One way the Space Force is looking at building resilience is through proliferation—launching greater numbers of less exquisite and expensive satellites. Saltzman pointed out the benefits in taking advantage of lower-cost satellites and less costly launch services to constantly refresh constellations.

“When I learned about satellites, launch was so expensive, the missions were so exquisite, we had to build satellites to last a long time in orbit,” Saltzman recalled. On a recent trip to Buckley Space Force Base, Colo., he said, he watched new operators fly old satellites. “They’re flying satellites from my early days in the military,” he pointed out. The technology associated with a satellite that was launched 25 years ago is 25 years old. … So the idea of smaller satellites also gives us an opportunity to change our refresh rate on how fast we can put new technology on orbit.”

Other ways to achieve resilience include increased maneuverability—launching satellites with enough fuel to move in orbit as needed to avoid threats—and leveraging commercial capabilities as more and more private companies launch satellites into low-Earth orbit for things like communications and imaging. That gives the Space Force more options if its native capability is compromised.

Ukraine has made great use of commercial satellite services to resist Russia’s invasion, and while that has led to some concerns about civil and private satellites being targeted in a conflict, Saltzman affirmed the Space Force is working to more formally define how commercial capabilities can be called upon, as the Air Force does with its Civil Reserve Air Fleet (CRAF) of commercial aircraft to expand airlift capacity in emergencies.

“It’s almost like a CRAF fleet, if you will, with arrangements that we can have with commercial providers,” according to Saltzman. “So do we have ready access in crisis to extra capacity? We’re in the very early stages of kind of sorting out what they want. There’s a lot of contract work to be done, a lot of legal work to be done to make sure that that’s all in place.”

The details are complicated for an industry that doesn’t want to see its unique business assets targeted.

“The question is: When we actually go to war, what happens to those systems and how do we think about our commercial partners?” asked Kay Spears, vice president and general manager of space, intelligence, and weapon systems at Boeing Defense Space & Security. “If they lose a system, what is the liability? Is the Space Force willing to cover that liability?” Further, what constitutes liability—current revenue losses or future losses or both? “Are they willing to take that risk?” Spears asked. “It just raises, in my opinion, a lot of new questions about how we leverage commercial. But it’s not an ‘If’—it’s a ‘How.’”

Counterspace Campaigning

Saltzman also advocated for what might be called responsible counterspace campaigning—a dramatic change from years past when talk of fighting in space was taboo.

Saltzman said the Space Force is “investing in capabilities that protect our joint force from space-enabled targeting while understanding that we cannot have a pyrrhic victory in this domain.”

What exactly those capabilities are remains a mystery—most of the service’s offensive and defensive capabilities are classified.

But there’s no questioning the Space Force’s intent to keep developing its ability to deter and fight if necessary. One of three lines of effort Saltzman has defined is fielding “combat-ready forces.”

Vice Chief of Space Operations Gen. David D. Thompson said the importance of preparedness for the Space Force cannot be overstated.

“Especially in the early days of a conflict … we are going to struggle greatly to have access to the air, to the sea, to land spaces around that matter,” Thompson said. “The only way we will do that is if in those early days we succeed through space.”

USAF Goes All In on ACE

By Chris Gordon

AURORA, Colo.

When the Pentagon and think tanks run wargames on a potential war with China, they envision U.S. air bases and ports attacked from the outset by Chinese ballistic and cruise missiles. The Air Force solution: Build more bases, create more targets, and move aircraft around.

“It’s to make the targeting problem for the adversary more difficult,” said Gen. Kenneth S. Wilsbach, commander of Pacific Air Forces, at the AFA Warfare Symposium in March. “It makes them use more munitions. And it gives us the chance to keep airpower in the air to create effects.”

The Air Force calls this Agile Combat Employment.

Each of the military services is seeking to adapt to the challenges of a potential Pacific war. The Air Force has ACE; the Space Force wants more proliferated, resilient satellites; the Marine Corps is reorganizing to create a lighter, more flexible force, the Navy wants more submarines, and the Army hopes to field a new hypersonic missile in the fall—though at this point, it still faces the problem of finding a place to base it.

Air Force operators do their work at 500 miles per hour, but their bases do not move. To keep the enemy guessing, ACE seeks to rapidly move aircraft and operations around the theater, and building more airfields is one key to making that work.

Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall at the AFA Warfare SymposiumWe’re generally trying to expand the target sets potential adversaries are going to have to worry about.

The Air Force plans to spend about $1.3 billion to make ACE a reality in fiscal 2024.

“We’re generally trying to expand the target set potential adversaries are going to have to worry about,” said Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall during the AFA Warfare Symposium in Aurora, Colo. “We’re trying to make the idea of Agile Combat Employment meaningful.”

ACE responds to China’s emergence as a near-peer adversary with advanced, long-range missiles, significant intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capability, and a strategy intended to deny major overseas bases to U.S. operators in a conflict. China has also rapidly increased the number of satellites it has in orbit to 260, many of which the U.S. military believes are specifically intended to track U.S. and allied forces.

“Let’s be honest, that’s all about find, fix, track, target—against Airmen, against Sailors, against Soldiers, and Marines that are there to fight in that theater,” said Brig. Gen. Anthony J. Mastalir, the commander of the Space Force’s Indo-Pacific component. That unit was established in November to give INDOPACOM its own native Space operations liaison.

Such threats mean the Air Force must assume it may not be able to operate aircraft from its permanent air bases overseas. Instead, leaders must anticipate having to disperse forces to austere nontraditional air bases.

“Air bases are no longer considered a sanctuary from attack, regardless of their location,” according to Air Force Doctrine Note 1-21, which defines the elements of ACE.

Lt. Gen. Tony D. Bauernfeind, the head of Air Force Special Operations Command, said the change is a natural response to U.S. success over the past 30 years.

“If we look at the last three decades, our adversaries have been looking at the American way of war,” Bauernfeind said. “What do we do? We power project, we established super bases. We establish our forces and once we’ve collected ourselves, then we proceed forward with our offensive operations. Our adversaries have taken full note of that and they are going to attack our bases in a quite aggressive manner. It’s a critical vulnerability that we have. [Now,] we have to have these forces that can power project at [other] locations and be able to shoot and scoot.”

Expanding ACE

ACE may take somewhat different forms in different theaters. In Europe, the Air Force faces the “tyranny of proximity.” Massive installations, such as Ramstein Air Base in Germany, a major hub for refueling, staging, and medical support, could be subject to a Russian missile attack.

In Asia, the Air Force faces the “tyranny of distance.” Many U.S. bases are thousands of miles from one another. For example, Guam, the westernmost U.S. territory in the Pacific, is home to Andersen Air Force Base, which provides U.S. planes free access to land and stage without foreign government approval. Roughly one-third of the entire island is home to some form of U.S. military installation. To disperse its forces, ACE aims to shift away from such centralized infrastructure in favor of a “hub-and-spoke” system of smaller operating locations. Large bases, however, will not go away.

“To be successful we need to have the right amount of prepositioned materiel, at the right scalability, so that it is available or arrives in time to meet the need, but not overdoing it to the point that it rots in the tough climate and environment that we face in the Indo-Pacific,” said Brig. Gen. Paul R. Birch, then commander of the 36th Wing out of Andersen Air Force Base in Guam. “Base protection is also imperative, and it can take many forms. At the same time, being a target isn’t our main focus. Rather, the focus is getting our airpower off the ground in a way that is lethal.”

In March, F-22 Raptors deployed to the spartan island of Tinian, the next island up from Guam in the Northern Mariana Islands. Tinian hosted U.S. warplanes in World War II, but this was the first time the Air Force’s premier air-superiority fighters had ever operated there. And it immediately followed the staging of F-35 Lightning IIs there in February.

Ensuring remote bases can support U.S. forces with prepositioned equipment, fuel, and adequate runways is hardly automatic. The Air Force is investing billions to bring locations like Tinian up to basic standards.

“There’s not much there,” Wilsbach said. “There’s a runway, a taxiway, a very small ramp, and a very small terminal that acts as the commercial terminal and the other half is our ops center.”

The Department of Defense is committing to expanding basing on Tinian, with the goal that the base can eventually serve as a “divert” airfield for Andersen. In blunt terms, that means if Andersen is attacked, USAF can move operations to Tinian. The Air Force will begin to invest in ACE infrastructure at an array of locations in the 2024 budget.

For PACAF, Tinian is a natural starting point for ACE operations, with a preexisting airfield on U.S. land. But the more austere the location, the more the Air Force needs to make sure it can actually operate from there. ACE hubs, such as Guam, already exist. Now it’s time to ensure the spokes are ready to support operations, as well.

“We have places where we can go that are ready for us,” Kendall said. “We have prepositioned equipment in some cases, as well as the other infrastructure we’re going to need to operate successfully.”

ACE will require Airmen to be more flexible, to take on duties outside their specific job descriptions. Air Force leaders say Airmen already possess the quick-thinking and inventive nature to take on roles they haven’t done before, but training them to be “multi-capable” is still a work in progress.

“We’re emphasizing multiple-capable Airmen for a variety of reasons,” Kendall said in explaining the investment necessary to make ACE work. “We want our people to have skill sets to do more than one job, because, quite frankly, our forward air bases are going to be attacked. We’re going to want to be able to move people out and have them do things in smaller numbers available at a given location, but also have the resilience to absorb casualties. We have to. The reality for the Air Force in particular, even for some Space Force humans, is that they’re going to be at risk. They’re going to have to fight against stressing threats in a way in which they’re going to be operating under fire.”

The exact breakdown of what multi-capable Airmen will officially mean and what skills will be required from whom is still being determined. But the Air Force says it will begin to spend money in the 2024 budget to begin a formal training process.

As for ACE bases, Guam and Tinian are over 1,700 miles away from Taiwan, the likely flashpoint in a conflict between the U.S. and China.

The U.S. is moving to secure more basing and overflight fights in the Pacific, such as an agreement with the Philippines to eventually base some American military assets and forces there and a plan to provide nuclear-powered submarines to Australia and forward deploy American submarines there. Other allies such as Japan are strengthening their alliances with the U.S. Staging American troops on the Japanese home islands is a sensitive political issue, but the two countries are growing increasingly aligned. In the future, the U.S. might spread out from Japan’s large air bases at Kadena, Misawa, and Yokota.

“There are over 600 airfields within 2,500 miles” according to AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies. “So, while stealth bombers will be key, so will stealth fighters creatively based across the area of operations.”

In many ways, ACE is a throwback to earlier times. The Army Air Forces used a similar model in the Pacific campaign during World War II, throughout the U.S. island campaign.

“We’re returning to our roots,” Bauernfeind said. “Nobody complained and said, hey, ‘I’m just a maintainer. I’m going to do maintenance, It was all hands on deck as they established that airfield and brought in combat airpower and made it happen.”

Who’s in Charge

Another throwback aspect of ACE is the independence necessary for detached operations.

“The definition of command and control and how we thought of it was just with an air operation center,” Lt. Gen. Alexus G. Grynkewich, the commander of Air Forces Central said. That’s not going to be the case in the future.

In the Middle East, the air force has a number of small air bases, many in undisclosed locations. AFCENT has a cluster of bases under an Air Expeditionary Wing commander, and when they get an air-tasking order, Grynkewich doesn’t want, or need, to control every aspect of what they do next.

“I’m not going to tell them what base to generate from,” Grynkewich said. “I’m not going to tell them what base to land an aircraft at. I’m just going to tell them what mission it is that they need to fill and they need to get that line where it needs to go. But if I try to manage their cluster base, I won’t have the situational awareness as to how much gas or the location of the right munitions there or not.”

Grynkewich quoted an old mentor explaining this phenomenon: “I’m always in command, but I’m not always in control.”

That will be the key to ACE.

How to Solve the Recruiting Crisis

Incremental fixes and sharing your own story can

turn the tide on today’s shortfalls, leaders say.

By David Roza

From 2007 to 2017 the British cycling team made a series of “1 percent improvements” in every aspect of their operation; combined, the changes helped the team win a streak of international medals.

Faced with a projected 10 percent shortfall in recruiting, Maj. Gen. Edward W. Thomas, head of the Air Force Recruiting Service, aims to apply the same strategy.

“There wasn’t going to be a new bike, a new way to race—it was improvements by 1, 2, 3 percent in a hundred different areas,” Thomas said at the AFA Warfare Symposium. “That’s where we are in recruiting today. Much to our disappointment, there is not one silver bullet. But there are many things that we can do better.”

Changes in the works are eliminating policies that exclude highly qualified candidates, such as restrictive tattoo policies, offering better incentives for recruits, such as college loan repayments, and more strategically placing recruiters to areas where they will be more likely to find successful candidates.

The biggest problem today, Thomas said, is simply finding people interested in joining the military.

AFRS Commander Maj. Gen. Edward ThomasAmerica is changing, and those applicants coming to us are changing. We’ve got to be able to adapt.

“This has been a slow-moving train that’s been coming at us for decades, frankly,” Thomas said. “There are less veterans, less service members, less bases, less opportunity to be exposed to what it means to serve in uniform today … the longer-term challenge of lack of familiarity is one that we’re going to have to come to grips with as a nation.”

This theme came up throughout the AFA Warfare Symposium, where top Air Force and Space Force officials urged Airmen and Guardians to help overcome negative perceptions or unfamiliarity with military service by sharing widely their own stories of service.

“Retention numbers look very good,” Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall said in his keynote address March 7. “We’re keeping the people that we get. But we need to get more people.”

Strong Headwinds

The Air Force Recruiting Service is flying into turbulent times. Having barely reached its fiscal 2022 goal for the Active-duty Air Force—and missed its goals for the Guard and Reserve by 1,500 to 2,000 recruits each—recruiters went into fiscal 2023 in the hole, projecting to come up 5,000 recruits short for the Active-duty alone.

Coming out of the pandemic when recruiting went almost entirely virtual, the Air Force now faces low unemployment and rampant negative misperceptions about military service, some even fueled by veterans complaining about today’s force.

Today, unemployment stands at 3.4 percent, the lowest since 1969, according to the Department of Commerce. Worse, only 23 percent of American youth are eligible to serve in the military, Thomas said, and only 9 percent say they are interested in serving.

With margins that small, the recruiting service needs to eliminate as many barriers to entry for qualified candidates as possible.

The service changed its tattoo policy March 1 to allow a single tattoo on each hand, not exceeding one inch in size, as well as one tattoo on the neck not exceeding one inch—as long as the tattoo is behind an imaginary vertical line dropping down from the ear. Previously, the service permitted only ring tattoos on the hand and none on the neck.

“America is changing and those applicants coming to us are changing,” Thomas said. “We’ve got to be able to adapt. We were literally turning away highly qualified applicants because of a small tattoo that was between their fingers, saying, ‘We wish we could make you an American Airman but why don’t you walk next door to the United States Navy?’”

On March 10, the Air Force unveiled another change, reinstating the Enlisted College Loan Repayment program that promises repayment plans of up to $65,000 to help recruits settle their student loans and still take advantage of the GI Bill.

Thomas said the Air Force is also working with the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services to expedite the naturalization process for U.S. permanent residents who join the branch.

“I find as we travel—whether it’s in Brooklyn or Miami or different parts of the United States—that we’ve got a lot of U.S. legal residents who are high-performing,” Thomas said. “They’re high quality, they’re hungry, they’re patriotic, and they want to serve. And we want to be able to get to them.”

If each small change such as these can get a few more hundred recruits in the door, Thomas hopes the Air Force can make up its shortfall.

“We are making smart changes where we were unnecessarily preventing otherwise highly qualified people from coming into the service,” he said.

‘Reintroduce Ourselves to America’

Eliminating barriers is only going to solve some of the problem, however. The more central issue is that military service is fading from view to most high school graduates today.

The Air Force was more open to visitors when Thomas first commissioned in 1990. Back then, busloads of schoolchildren visited for tours around bases, the services sent speakers out to talk about Air Force life with the local community, and open houses for people to visit were the norm. But multiple rounds of base closures, increased security measures after 9/11, reductions in force, and two decades of high-tempo counterterrorism operations have made the service less visible to the public.

Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr. has directed commanders “to get back out and reintroduce ourselves to America,” and by that he means more than just the local community. Instead, the Air Force must reach into all “those areas where the connection is a very thin thread at best,” Thomas stated. “Those are the areas that we need to be able to reconnect with America.”

Fifty years after eliminating the draft and establishing the all-volunteer force, the military is coming face-to-face with the fact that the number of Americans who served or know someone who served continues to decline.

Today, the Air Force can no longer depend on a population “of propensed or interested individuals, those that are already leaning toward the military,” Thomas explained.

“We have to be able to connect and reintroduce ourselves to America in a way that we interest the eligible, that we expand that pool.”

Pay and benefits go only so far. The military may not always be able to compete on straight compensation, so instead it must emphasize the sense of purpose, camaraderie, and personal growth that define the service experience.

“We are shifting our advertising strategy to focus more on that transformational message … serving your community, doing things that matter, doing things that will help the nation, help your family, help grow you as a person,” Thomas added. “We are looking to be able to connect at that level, to reach people’s passion and their desire for a purpose-driven life.”

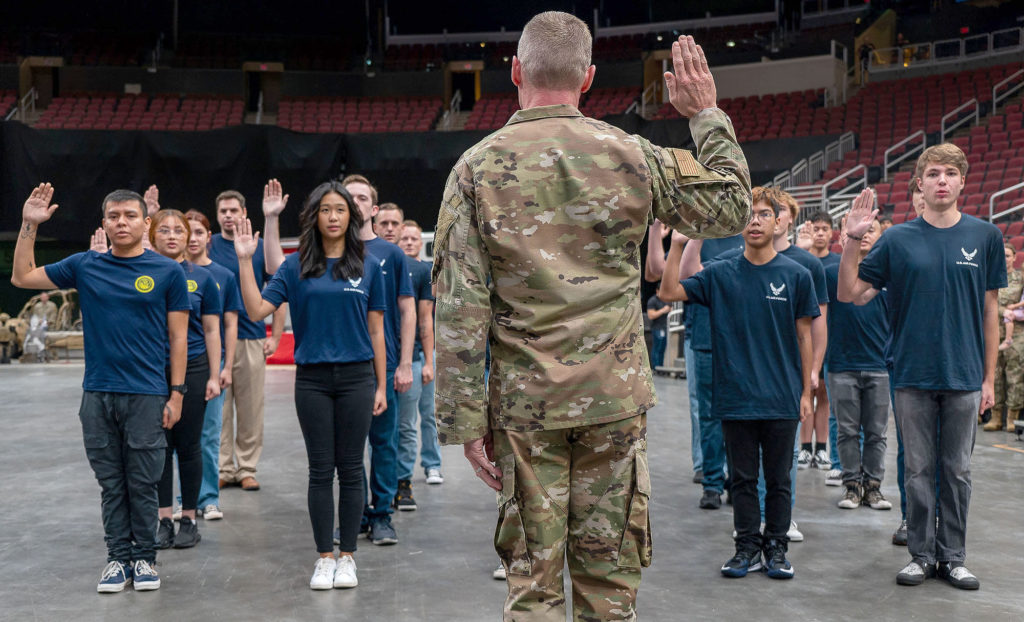

Chief of Space Operations Gen. B. Chance Saltzman, Vice Chief of Staff of the Air Force Gen. David W. Allvin, Chief Master Sergeant of the Space Force Roger A. Towberman, and Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force JoAnne S. Bass are all singing from the same songbook. The four implored Airmen and Guardians at the symposium to go home and tell their stories.

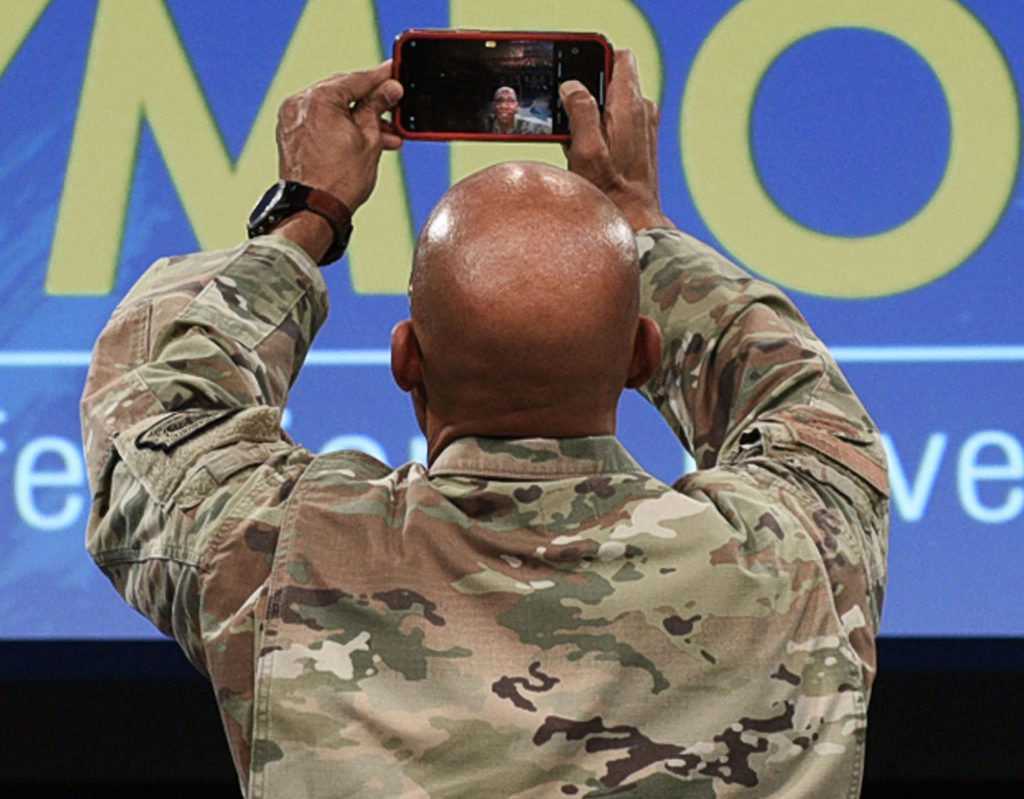

So did Air Force Chief of Staff Brown, who asked everyone in attendance to take out their phones, take a selfie, and send it to everyone they knew saying, “Because of me, airpower is the answer.”

Brown took out his own cell phone, turned around, so that the standing-room-only crowd of 4,000 was behind him, and said “I’m going to send it to my mom. … Because of our Airmen, airpower is the answer.”

Saltzman recalled that he joined the military to pay for college, then stayed on “because all of a sudden there’s relationships and people you like and respect, and it’s a fun group to hang out with,” he said. “So you take the next job, and you take the next job. And before you realize it, you have this sense of purpose.”

When Saltzman went home for visits, it seemed many of his civilian friends did not have that same sense of duty or purpose. Suddenly, service was a special point of pride.

Towberman’s journey was different. For him, the Air Force became a refuge, a place to get his life back in order.

“I messed up my life in every way imaginable between 17 and 22,” said Towberman, the second Guardian in the Space Force’s history. “I’ve stolen food to feed myself. It doesn’t matter what I do—I don’t think my debt to the United States Air Force, and now Space Force, will ever be paid.”

Towberman called on his fellow service members “to play offense” to help build up the Air and Space Forces, to share their own stories of joining and staying in the military as an inspiration for others who might follow in their footsteps. Bass echoed the sentiment.

“The best recruiters are every single one of our Airmen, every single one of our Guardians,” she said.

The 2021 document, the “Guardian Ideal” was designed with that in mind.

“Our commitment to Guardians is to not give them a reason to quit this team,” Towberman said. “That’s where the focus has to be. … We’re really focused on providing Guardians an experience that matters to them, that they feel empowered, that they feel cared about, that they’re connected to each other and to the mission.”

In recent years, the military has been increasingly portrayed as a place where young people become damaged, either through physical or emotional trauma, chemical exposure, or even poor leadership. That is not the military most Airmen or Guardians experience, the leaders said.

“Get out there, be proud, puff up your chest, tell people your stories and tell them your whole story—that’s what they need to hear from us,” Towberman said. “This is an opportunity like no other, where, especially on the enlisted side, on Day One of service, you can literally hit the reset button on your entire life and do anything you want to do.”

Opportunities like that, he said, “just don’t come along every day.”