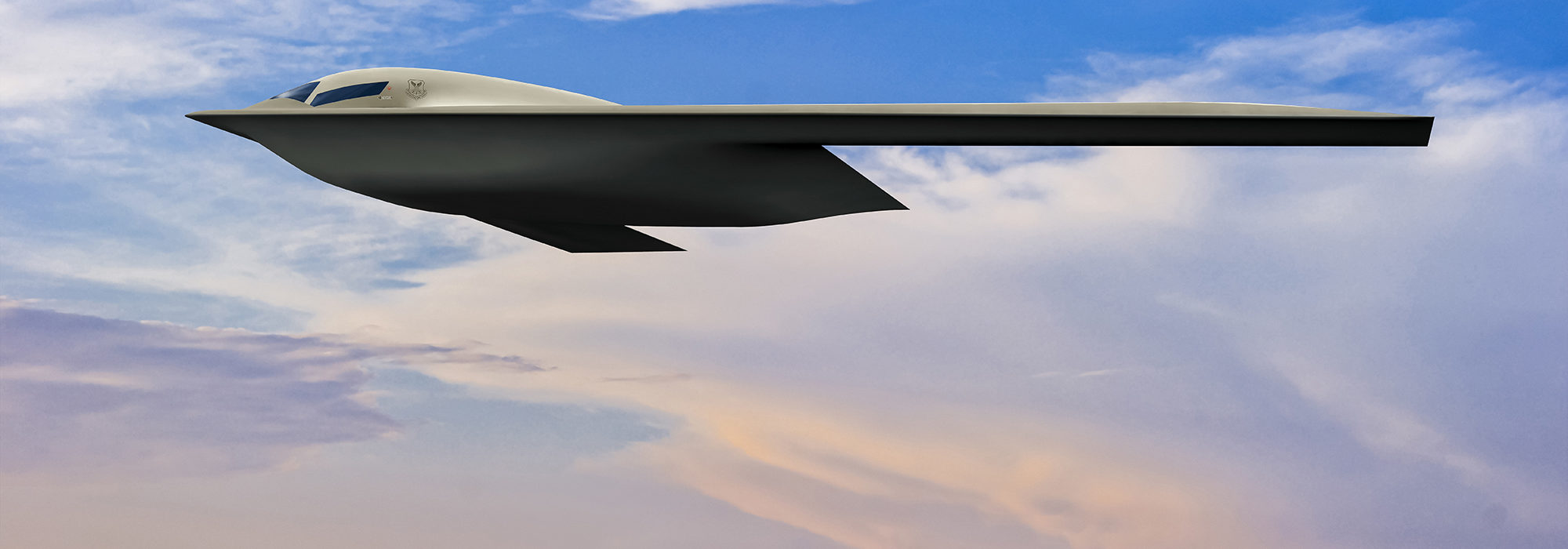

B-21’s First Flight Postponed to 2023

By John A. Tirpak

The first B-21 bomber will not make its first flight until 2023, at least six months later than planned, the service said in May. While leaders offered no single explanation for the setback, the service said the Raider program is still on track to meet baseline cost, schedule, and performance targets established at Milestone B award.

Rapid Capabilities Office director Randall G. Walden, who predicted last year that the B-21 would fly in “mid-2022,” said in March the first flyable B-21 was largely assembled and starting calibration testing. Air Force and industry sources still expect the first B-21 to be rolled out this calendar year.

Lt. Gen. David S. Nahom, the Air Force’s deputy chief of staff for plans and programs, said in May that as many as 145 B-21s could be needed, a 45 percent jump from the 100 specified earlier. But a full acquisition plan and strategy still awaits completion of engineering and manufacturing development, and the requirement could shift with emerging strategy and technology.

Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr. told the Senate Armed Services Committee on May 3 that an “ongoing analysis” of B-21 requirements and indicated how many “other capabilities that work with the B-21”—such as additional escorts—could alter the equation. Brown said the Air Force is “working through crewed and uncrewed collaborative platforms that can work very closely with the B-21.”

Calling the program “on track,” Brown also said the Air Force is doing all it can to ensure the plane is “easier to maintain … to increase aircraft availability.”

Members of the Senate and House Armed Services Committees have praised the B-21 program, with Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.) calling it an “exquisitely run program.” The Air Force plans to invest nearly $20 billion in B-21 procurement and another $12 billion in research and development over the five years from fiscal 2023 through 2027.

The B-21 is planned to succeed the B-1B and B-2 bombers, but exactly when remains unclear. The Air Force has long promised the B-21 will be a “available” for combat use in the “mid-2020s” and announced three years ago that it would retire its B-2s and B-1s in 2031 and 2032, respectively. But Nahom said all plans hinge on the B-21’s progress and pledged the aging bombers will remain until they “shake hands” with the B-21s that replace them.

As for when the first B-21 takes to the skies, an Air Force spokeswoman would say only that will be “data- and event-driven, not a date-driven event.”

Next Air Force One Will Arrive 2-3 Years Late, USAF Says

By John A. Tirpak

The next presidential airplanes will arrive up to 36 months late, the most recent program delay to strike a major Air Force acquisition. Assistant Air Force Secretary for Acquisitions, Technology, and Logistics Andrew P. Hunter told lawmakers in May that the VC-25B had slipped again, up from a 17-month delay reported earlier. It’s “quite a significant delay,” he said.

Boeing is the sole-source contractor for the next “Air Force One,” officially the VC-25B. There will be two aircraft, both 747-8s that are being customized for the role. Delaying a further two to three years “means we will have to sustain [the existing 30-year-old] aircraft longer,” Hunter said, which will have a direct impact on future budgets requiring “further resources to cover the gap.”

An Air Force spokesperson said the delay “is due to a combination of factors,” including “impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic,” a change of vendors for the interior work, “wiring design timelines and test execution rates.”

The Air Force “recommends” that the “objective”—or goal delivery time—should be set at 24 months, while the “threshold,” or must-have, be set at 36 months, according to the spokesperson. The Pentagon’s acquisition and sustainment chief, William LaPlante, will decide on the timing after “an update to the acquisition program baseline,” she said.

“Based on how the contract was written, as the expected completion date moves to the right, the threshold date also moves to the right,” she noted. “The new schedule baseline will contain the updated completion timeline.”

DOD’s LaPlante Sees Risk in Sentinel ICBM

By Greg Hadley

No sooner had William LaPlante been confirmed as undersecretary of defense for acquisition and sustainment in April than he announced a series of “deep dives” into plans to modernize the three legs of the nuclear triad, starting with the program he views as having the most significant risk—the LGM-35A Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile, known until recently as the Ground Based Strategic Deterrent.

LaPlante told the Senate Armed Services strategic forces subcommittee in May that of all the nuclear modernization efforts underway—including the B-21 bomber and the Columbia-class submarine—the Sentinel has the furthest to go.

“They’re somewhat early—one or two years into the engineering, manufacturing, and development—trying to get to a first flight,” LaPlante noted. “I would say … there’s still a significant risk.”

Radiation-hardened electronics and the nuclear infrastructure are the primary areas of concern, he said. “I intend to look into it, and I will give you that assessment of where that is,” LaPlante said.

The Sentinel, formerly called GBSD (for Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent) is to replace 50-year-old Minuteman III missiles and officials have said it cannot be further delayed without risking the credibility of the U.S. intercontinental ballistic missile force.

The Air Force is seeking $3.6 billion for the Sentinel program in fiscal 2023, plus $444 million in military construction for infrastructure improvements. Current plans would see initial operational capability by 2029.

Adm. Charles “Chas” A. Richard, head of U.S. Strategic Command, warned the Senate panel that any delays to that timeline will have real-world impacts.

“Weapons program delays have driven us past the point where it is possible to fully mitigate operational risks,” Richard said. “In some cases, we’re simply left to assess the damage to our deterrent. Further programmatic delays, budget shortfalls, or policy decisions to lower operational requirements to meet infrastructure capacity will result in operational consequences.”

Already, Richard warned, the U.S. has a “deterrence and assurance gap against the threat of limited nuclear employment.” That issue, Richard said, has been highlighted in recent months by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and threats to use low-yield nuclear weapons; and by China’s “strategic breakout” in rapidly and massively upgrading its nuclear arsenal.