Few issues over the past 80 years have led to more discord between the Army and the Air Force.

According to Air Force legend, the best way for airpower to support Army battlefield troops was proven in Operation Torch in North Africa in 1943. The trouble is that the ground forces were not that impressed with the proof, and they did not subscribe to the legend. Eighty years later, the issue remains unsettled.

Operation Torch, commanded by US Lt. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, began in November 1942 with a combined US and British invasion of Algeria. The goal was to link up with the British Eighth Army driving westward from Egypt and Libya and crush the German Afrika Korps in between them.

For US airmen, it was the first real combat experience against an enemy in proximity to friendly ground forces, a mission that would become known as “close air support,” or CAS. US airpower was controlled by the ground commander, who parceled it out in increments for the benefit of local ground units.

That approach—plus the demand for a defensive “air umbrella” overhead—was inefficient and ineffective. It scattered the air effort for limited and temporary results. German airpower took a punishing toll on US air and ground forces.

The priority was soon switched from local air patrols to establishing air superiority and attacking German forces and resources that had not yet reached the front.

The change worked to the clear advantage of allied ground forces, both in the results of the land battle and in reducing the losses the Germans were able to inflict. Luftwaffe attack sorties dropped by 80 percent, then dwindled to almost nothing. German rear echelons were increasingly unable to sustain operations at the front.

In April, tactical airpower resumed direct support of ground forces, flying as many as 2,000 sorties a day. The campaign ended in May with the surrender of 275,000 Axis troops.

This is much more effective than any attempt to furnish an umbrella of fighter aviation over our own troops.Army Field Manual 100-20

Operation Torch led to Army Field Manual 100-20, “Command and Employment of Air Power,” published in July 1943. It proclaimed land power and airpower as “co-equal and interdependent” and provided for theater commanders to exercise command of air forces through their subordinate air force commanders.

FM 100-20 was approved by the Army Chief of Staff, but without consultation or concurrence from the Army ground forces. It was celebrated by the Air Force as a “declaration of independence for airpower,” but the argument was just beginning.

The Coming of CAS

In 1914, the Army declared infantry to be “the principal and most important arm,” with the cavalry and artillery corps in support. When the Air Service emerged, it was regarded as another corps to “aid the ground forces to gain decisive success.” The strafing of trenches and enemy positions in World War I was a precursor of CAS.

A doctrinal split developed in the 1930s with the advent of the B-17 long-range bomber. In the Air Corps view, the most important mission was strategic bombardment. Establishment of air superiority came second.

“Attack aviation” was third. It made no distinction between interdiction—disrupting or destroying enemy capabilities before they could be brought to bear against friendly troops—and close air support.

FM 100-20 listed air superiority as the first priority for theater tactical aviation. “This is much more effective than any attempt to furnish an umbrella of fighter aviation over our own troops,” it said. Second priority was to “prevent movement of hostile troops and supplies into the theater.” A third priority was action “to gain objectives on the immediate front of the ground forces.”

Between 1943 and 1945, there were enough airplanes to supply regular support for ground troops in contact with the enemy, so the doctrinal disagreement was not a serious problem.

The Key West agreement of 1948 assigned postwar roles and missions to the armed forces. A major function of the Air Force, which had been created in 1947, was “to furnish close combat and logistical air support to the Army.”

CAS for Marine Corps ground units was left to Marine Corps aviation. “Marine Corps doctrine stressed that Marine airmen were soldiers first, flyers second, and that airplanes represented but one of a number of ancillary weapons the ground commander could use to support his infantry,” said historian John Schlight. Marine airpower remained constantly available to the ground commander and had no responsibility for gaining control of the air, isolating the battlefield, or air interdiction.

Air Force Col. (later Gen.) William W. Momyer observed that if Allied air forces had followed this doctrine in World War II, “the German Air Force would have been the victor” since it would have gone unopposed.

Culture Wars

The weight of evidence from conflicts since World War II confirms that the Air Force’s most valuable support for the Army—both to the outcome of the ground battle and in limitation of casualties—is air superiority and air interdiction.

Theater commanders, who must choose priorities for their airpower, generally understand this, but the perspective of the ground forces tends to be less analytical and more visceral.

Big threats may be more important in the long run—they are distant and out of sight. Ground units seldom know about them. The enemy confronting them directly is a matter of life and death. Close air support is a large factor in confidence and morale.

To the Air Force, CAS is part of a broader air campaign that also includes interdiction and air supremacy. To the Army, CAS is a vertical extension of the ground battlefield, and airpower is a supporting arm.

“CAS is a function vital to the mission of ground forces for successful combat at minimal cost,” the Association of the US Army said in 1993. “In the Army view, the Air Force is not greatly interested in the function and tends to neglect it in favor of strikes deeper into enemy territory.”

Such perceptions have been encouraged by Air Force statements on occasion, notably during the nuclear “massive retaliation” era of the 1950s. USAF doctrine in 1954 held that it was no longer necessary to defeat an enemy’s ground force.

The Army was also listening in the 1980s when program officials for the F-15 air superiority fighter, wrapped up in their zeal to hold down the airplane’s weight, adopted the slogan, “not a pound for air-to-ground.” The slogan was no indication of what the Air Force actually did. A multirole variant of the aircraft, the F-15E, went on to perform both air interdiction and CAS. It is still doing so—four decades later.

Korea and Vietnam

The prevailing image of the air war in Korea is the clash of F-86 Sabres and MiG-15s in MiG Alley along the Yalu River. That, however, was the lesser part of the effort by Far East Air Forces.

The great majority of FEAF missions were in aid of the ground battle: 23 percent of them close air support and 55 percent interdiction. In the early months of the war, FEAF threw everything it had, including B-29 bombers, against the North Korean invaders.

At first, the propeller-driven F-51 Mustang, which could operate from rough airstrips and which had a long loiter time, was used extensively for CAS. F-84E Thunderjets arrived in December 1950 and took over the main close air support tasking for the rest of the war.

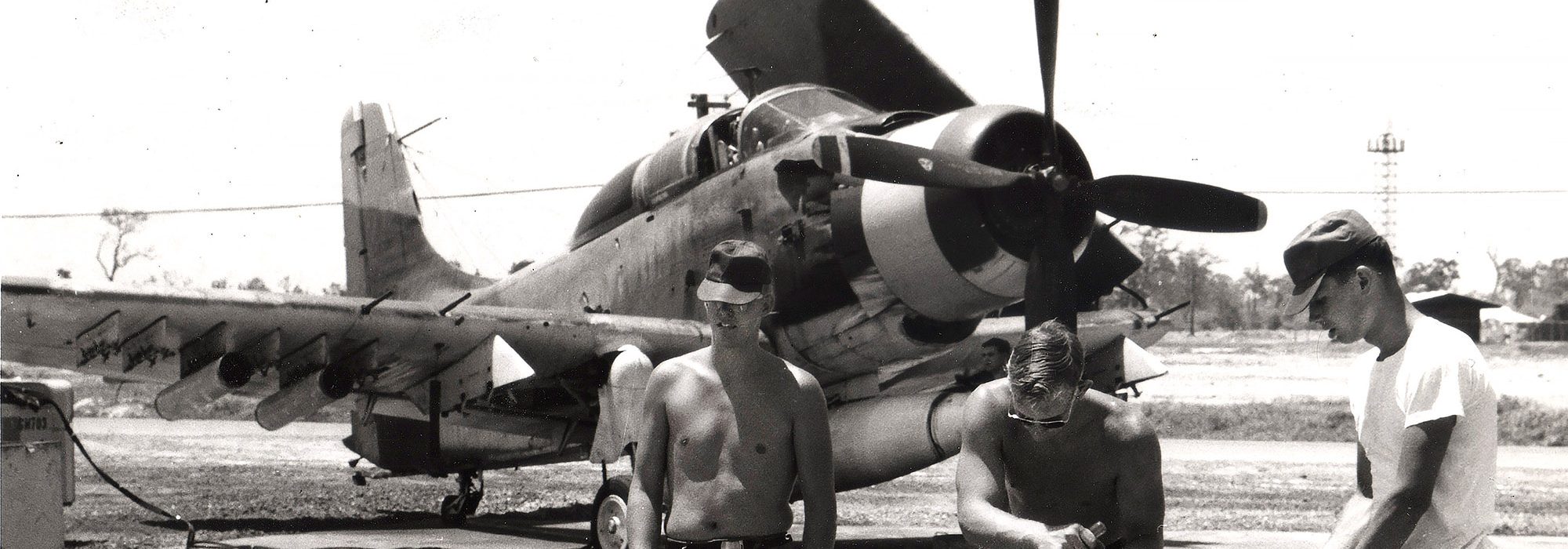

When USAF air commandos went to Vietnam in 1961 to train and assist the South Vietnamese, they flew vintage propeller-driven aircraft, the best of which was the A-1E Skyraider. The restriction on jet aircraft in Vietnam—seen as a possible violation of the Geneva Accords on Southeast Asia—was not lifted until the introduction of US ground troops in 1965.

The A-1Es, flying low and slow and able to loiter in the battle area, were popular with ground units, but improving enemy air defenses forced their withdrawal from South Vietnam in 1967. The main Air Force platforms for CAS were jets, the F-100 and F-4.

The Air Force flew air superiority and deep interdiction missions in North Vietnam and Laos, but the action in South Vietnam was in support of the ground war. Unlike previous conflicts, there were no fixed lines and few large engagements. Airstrikes were directed by forward air controllers in light aircraft. FACs were used occasionally in World War II and Korea, but they were fundamental to strikes in Vietnam. Eventually, improving defenses required “fast FACs” in jet aircraft.

When possible, CAS missions were planned ahead of time for coordination of the strike and selection of the best weapons. About 30 percent of the allocated CAS missions, though, were held back as an “immediate” resource for response to unexpected needs. It took about half an hour to get bombs on an immediate target, but in tight situations, an aircraft already in the air could be diverted.

It wasn’t exactly CAS, but the Army heartily appreciated the B-52 bomber formations that laid down saturation carpet bombing with high explosives in areas 1.2 miles long and about half-a-mile wide.

Special Airplane

In 1961, the Army introduced helicopters into Vietnam for “direct aerial fire support,” claiming that it was different from close air support, which was an Air Force mission. In 1966, the two services struck an agreement in which the Army would have all the combat helicopters and the Air Force would have all of the fixed-wing airplanes.

USAF, under pressure from Congress and the Department of Defense and fearing possible loss of the mission, announced in 1966 its intention to develop the “A-X,” the Air Force’s first—and so far only—specialized aircraft for close air support. Up to then, CAS had been an additional task for fighter and attack airplanes.

The A-X evolved into the A-10 “Warthog,” which became operational in 1977. The A-10A was relatively slow, with a top speed of 439 mph. Its main claim to fame was the seven-barrel rotary GAU-8 30 mm cannon that protruded from its nose.

In the original design, the Gatling-style gun could pump out 2,100 rounds per minute, later raised to 3,900, but it typically fired short bursts with a distinctive sound described as “Brrrt.” The A-10 airframe was essentially built around the gun.

A total of 713 A-10s were eventually built, and the ultimate model, the A-10C, could reach a top speed of 518 mph. The Army ground forces bonded with the A-10 and viewed with disfavor USAF’s proposal in the 1980s to replace it with a faster, multi-role aircraft.

There was a flurry of interest by the military reform movement in a notional airplane called “the Mudfighter,” slow and simple, heavily armored, and loitering above clusters of ground troops.

Meanwhile, the Air Force was moving in the opposite direction. Believing the A-10 could not survive in mid- to high-intensity conflicts in the 1990s, USAF evaluated 28 options for close air support and concluded that the “A-16,” a variant of the F-16 fighter, was the best choice.

“The data does not say ‘Mudfighter’, ” said Gen. Larry D. Welch, Air Force Chief of Staff. “No matter how you slice it, the data says ‘A-16’.”

The A-16 variant would have had stronger wings and a 30 mm cannon but it never went into production. Congress, in 1990, directed the Air Force to retain two wings of A-10s. Plans for the A-16 faded away.

AirLand Battle

The Army underwent an epiphany of sorts in 1982 with its “AirLand Battle” doctrine, which acknowledged that a war in Europe could not be won at the point of contact. CAS was still important, but defeat of Warsaw Pact forces required deep strikes and interdiction. The Army could not do it without the Air Force.

USAF’s Tactical Air Command embraced AirLand Battle in 1983. NATO also signed up, adding a “Follow-On Forces Attack” strategy aimed at destroying or disrupting enemy forces in rear echelons.

It sounded like what Gen. Carl A. Spaatz and RAF Air Marshal Arthur Coningham said in 1943, except for one thing: With AirLand Battle, the Army was always in charge and airpower was always the supporting force.

Air Force doctrine recognized “battlefield air interdiction,” a separate mission broken out from general interdiction, and referring to targets some distance from the front, but of special importance to ground operations.

To the Army, this was all part of an “extended battlefield.” The corps commander was authorized to set the “Fire Support Coordination Line,” within which the ground forces controlled all “fires,” including airpower. In time, Army commanders claimed the right to draw the FSCL hundreds of kilometers ahead of the positions they actually occupied.

With the Gulf War impending in 1990, US Central Command’s off-the-shelf Operations Plan 1002 was built around AirLand Battle. The assumption was that the ground forces would take the lead in Operation Desert Storm, which was about to unfold.

In the Gulf

To the surprise of all—especially the Army—the war plan chosen by the CENTCOM Commander, Gen. H. Norman Schwarzkopf, was not AirLand Battle. Instead, Desert Storm consisted of sequential phases, beginning with a 38-day air campaign. Ground forces did not play a major role until the final four-day phase, when the Iraqi forces were battered and reeling.

The early emphasis was on deep air operations against strategic “centers of gravity.” Sixty-seven percent of the overall air effort targeted the Iraqi fielded forces, but close air support accounted for only six percent of the sorties. Both the A-10 and the F-16 performed well.

Battlefield air interdiction was not included in the Desert Storm concept of operations or the Air Tasking Order. It was dropped from Air Force doctrine in 1992. AirLand Battle was eliminated from Army Field Manual 100-5 in 1993.

In the regional conflicts of the 1990s, airpower figured prominently, but very little of it was close air support. The nature of the engagements seldom called for it. In Operation Allied Force in Kosovo, US ground forces were not even employed. It was all airpower. The demand for close air support did not surge again until operations in Afghanistan and Iraq after 2001.

A-10s remained in the force following the Gulf War, although some of them were placed in storage in an overall reduction of Air Force combat wings. In response to criticism in 1994, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Merrill A. McPeak offered to give the Army the close air support mission along with the A-10s if the Army thought it could do the job better. His offer was declined.

The Joint Strike Fighter program in the mid-1990s led to the stealthy F-35 Lightning II, envisioned as a successor to both the F-16 and the A-10. It was to replace the Marine Corps AV-8 Harrier as well. In 2007, the Air Force began installing new wings on the oldest A-10s to extend their service life.

The service partnership hit another bad bump in Operation Anaconda in Afghanistan in 2002, when the Army division commander complained about slow delivery of close air support. What he did not mention was that the Army had underestimated the opposition, did not request CAS in advance, and did not notify the Combined Air Operations Center of the operation until hours before it started. Even so, the air component managed to put a substantial number of precision attacks on target the first day.

CAS for Future Wars

In recent years, the main dispute has been about what kind of airplane should be used for close air support. In 2013, Congress failed to meet its self-imposed deficit reduction goals. This triggered a massive budget sequester, with half of the money to be taken from the armed forces.

The Air Force, searching for big savings available by eliminating entire programs, proposed to retire the A-10s. The Warthog was getting old and was no longer capable of surviving in high-threat environments. Accusations arose immediately from the ground forces and Congress that this was another attempt by the Air Force to abandon CAS.

Exasperated, USAF chief Gen. Mark A. Welsh III—himself a former A-10 pilot—said that “CAS is a mission, not a platform,” that the Air Force was flying 20,000 close air support sorties a year, and that about 80 percent of those flown in Afghanistan since 2001 were by aircraft other than the A-10. The F-16 alone had flown more CAS missions than the A-10.

No matter. The A-10 was a symbol of commitment to soldiers engaged in close combat, and Congress refused permission for its retirement. The Air Force announced that the A-10 would remain in the inventory until the 2030s and that an additional number of them would get wing replacements.

For the foreseeable future, CAS will be divided up between two domains. Against low-technology adversaries or when the opposition is minimal, the Air Force will use A-10s and perhaps modified light aircraft. Army AH-64 attack helicopters will most likely be restricted to this regime as well.

In high-threat conflicts, the preferred choice for CAS will be the F-35, with which the Marine Corps also proposes to replace its CAS AV-8 Harriers. A problem in this is that the Air Force has only about 200 F-35s altogether, far short of the 1,763 on which it had planned.

“Although in isolation CAS rarely achieves campaign-level objectives, at times it may be the more critical mission due to its contributions to a specific operation or battle,” current Air Force doctrine says. “CAS should be used at decisive points in a battle and should normally be massed to apply concentrated firepower and saturate defenses.”

That is stated cautiously, but it is not far from what Coningham and Spaatz said in 1943.

John T. Correll was editor in chief of Air Force Magazine for 18 years and is a frequent contributor. His most recent article, “Disaster in the Philippines,” appeared in the November issue.