How the Air Force helped avert a nuclear catastrophe and save the world.

“This is not a bluff.” Russian President Vladimir Putin’s warning in September 2022 made clear his apparent willingness to use “all weapon systems available to us”—including nuclear ones—in the war in Ukraine. Decades after the end of the Cold War and 60 years after the Cuban Missile Crisis, the serious specter of nuclear war was once again in the popular consciousness.

Weeks later, President Joe Biden told Democratic Party faithful at a fundraiser, “We have not faced the prospect of nuclear Armageddon since Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis.” What Biden was forgetting—along with politicians, pundits, and reporters across the political spectrum—was that America and the Soviet Union teetered on the brink of nuclear war far more recently than 1962. Most Americans are unaware that in 1983, in the midst of President Ronald Reagan’s first term, the world came close to nuclear Armageddon.

The 1983 incident was at least as dangerous as the Cuban Missile face-off in October 1962. Yet the 1983 scare remains largely unknown and unexamined, a missed opportunity given that the events of autumn 1983 offer policymakers, military leaders, and intelligence officers significant lessons for current challenges, especially in regard to how to prevent the war in Ukraine from escalating into a nuclear conflict.

Unlike the 1962 event, when President John F. Kennedy’s televised speeches received blanket coverage and alarmed the world, the 1983 crisis played out largely out of public view. Americans are well familiar with how Kennedy and his administration were in formal and informal contact with the Kremlin throughout the crisis, and the dramatic confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union in the United Nations Security Council played out on live TV.

Classification kept the most of the 1983 events in the shadows, however, until around 2015, when some government papers were finally declassified. Another difference from 1962 is that the 1983 events were not concentrated in anything like the 13 days of the Cuban crisis. Rather, the events played out over a much longer time frame. In 1962, the White House publicly trumpeted its resolution of the crisis. But in 1983, the White House didn’t even realize it was dealing with a nuclear crisis until after it had passed.

Indeed, the full scope of the 1983 crisis was not understood at the time by the Intelligence Community (IC). The various sub-crises were resolved quietly, out of the public eye. The interconnectedness of the 1983 crises was better understood in Moscow than in Washington, mainly because of a global KGB-led intelligence collection program.

To understand this history, it’s important to appreciate the mindset of the Kremlin at the end of the 1970s. The aging Communist Party leadership in Moscow worried that the global correlation of forces was moving inexorably in favor of the West. The Soviets judged that they were falling behind on many fronts—economic growth, technology development, and geopolitics. Because of those factors, the Kremlin also feared that its ability to keep pace with the West in military terms was threatened.

Moscow’s geriatric leaders obsessed about a potential surprise attack from the West. Most of them had personal memories of the shock of Germany’s Operation Barbarossa, a devastating surprise attack on the USSR in 1941. They feared the West could launch a Barbarossa-like nuclear first strike. To prevent a repeat of 1941’s strategic surprise, the KGB initiated Operation RYaN in May 1981, the largest Soviet intelligence-collection effort of the Cold War. Its purpose: to uncover secret Western preparations for a nuclear first strike. The Russian acronym RYaN translates to “nuclear missile attack,” implying a surprise attack.

In effect, the KGB had concluded that the West was likely to execute a first strike, and tasked intelligence officers around the world to find facts to support that conclusion. The chief architect of the operation was KGB Chairman Yuri Andropov, who in November 1982 was named General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party. Andropov feared the West’s ability—and suspected its willingness—to launch a decapitating nuclear first strike.

General Secretary Andropov viewed President Reagan with deep suspicion, and his distrust seemed justified when Reagan dubbed the Soviet Union the “Evil Empire” in March 1983, asserting the Russian government was the “focus of evil in the modern world.” Soon after, in the same month, Reagan first revealed the existence of the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), an ambitious plan to defend the Earth from intercontinental ballistic missiles with space-based defenses. The concept was immediately dubbed “Star Wars,” drawing from the movie franchise which had not yet released its third installment. Those two speeches raised Andropov’s concerns to a fever pitch, and he ordered a redoubling of the RYaN effort. The Western press may have been Star Wars skeptics, but the Soviet leadership believed it could be built, and that it would be a singularly destabilizing advantage for the West. If SDI were successful, the Kremlin concluded, the United States would possess the ability to launch a nuclear first nuclear strike with impunity.

Kremlin worries also focused on NATO and on planned U.S. deployments of new Pershing II nuclear-armed ballistic missiles in West Germany and new nuclear-armed ground-launched cruise missiles in the United Kingdom. The Kremlin viewed both weapon systems as first strike threats that could decapitate the Soviet leadership with virtually no warning. To the Politburo, NATO was an inherently offensive alliance. (Today, Vladimir Putin echoes much the same sentiment about NATO.)

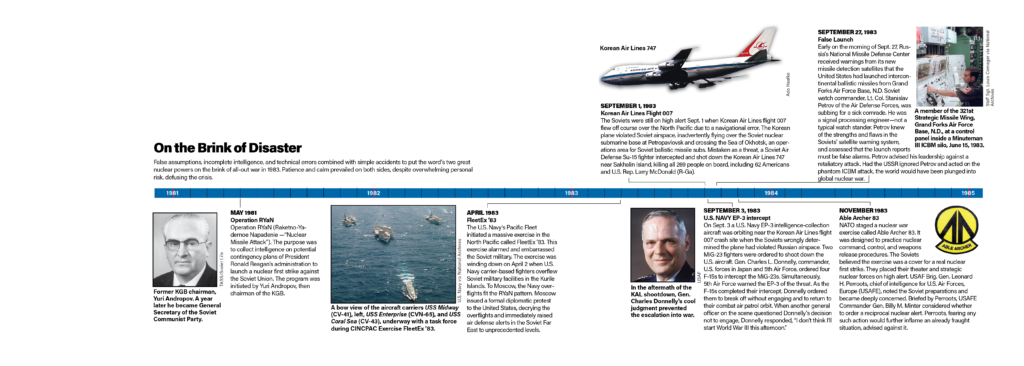

With this as a backdrop, the Soviets saw a series of events in 1983 that seemed to validate Operation RYaN’s premise and the Kremlin’s paranoia. The same month as Reagan’s “Evil Empire” and “Star Wars” speeches, the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Fleet initiated a massive exercise in the North Pacific. Called FleetEx ’83, it would both alarm and embarrass the Soviet military. The exercise was winding down on April 2, 1983, when U.S. Navy carrier-based fighters overflew Soviet military facilities in the Kurile Islands. To Moscow, the Navy overflights fit the RYaN pattern. Were these violations of Soviet airspace an attempt by the Americans to create a predicate for a nuclear first strike? Moscow issued a formal diplomatic reproach to the United States decrying the overflights and immediately raised air defense alerts in the Soviet Far East to alarming levels.

Soviet Air Defense officers in the Far East were fired for failing to respond to the U.S. Navy overflights. Across the Far East, Soviet air defense units maintained a maximum, hair-trigger alert through the summer months of 1983. No Soviet colonel wanted to be the one to fail to respond should another violation of Russian airspace occur.

In Japan, Air Force Intelligence assessed that the Soviet alerts posed a grave potential threat to American intelligence-collection flights in the Far East. In July, 5th Air Force Intelligence warned Adm. William J. Crowe, the chief of the U.S. Pacific Command, that any aircraft deemed a border violator by the Soviets—even a civilian airliner—would be at grave risk.

The Soviets were still on high alert on Sept. 1, 1983, when Korean Air Lines flight 007, flying from New York to Seoul, via Anchorage, Alaska, flew off course over the North Pacific due to a navigational error. The Korean plane violated Soviet airspace, inadvertently flying over the Soviet nuclear submarine base at Petropavlovsk and crossing the Sea of Okhotsk, a bastion for Soviet ballistic missile subs. The Soviet Air Defense system was uncertain of the aircraft’s identity and attempted to intercept the intruder several times. As KAL 007 was about to exit Soviet airspace, a Soviet Air Defense Su-15 fighter finally intercepted and shot down the Korean Air Lines 747 near Sakhalin Island, killing all 269 people on board, including 62 Americans.

To the Kremlin, the KAL incident fit the RYaN pattern. It was either a clever American intelligence-collection flight, or it was a deliberate provocation designed to create a pretext for a nuclear war. To this day, many Russian leaders believe the KAL flight was a deliberate act of American aggression.

Air Force Intelligence concluded that the Soviets were confused about the mystery aircraft’s identity during the early morning hours of Sept. 1. Inadvertently, KAL 007 flew through the orbital path of an Air Force RC-135 Cobra Ball mission that was monitoring a predicted Soviet ICBM test launch. But when the ICBM launch didn’t occur, the RC-135 returned to base, while the Korean 747 flew blithely on toward the Kamchatka Peninsula and Soviet airspace, well to the north of its planned route. The mystery flight confused and confounded Soviet commanders.

The KAL shootdown took the already frayed US-Soviet relationship to a breaking point. Official communications between Moscow and Washington essentially ceased—quite unlike what happened 21 years before during the Cuban Missile Crisis, when President Kennedy exchanged frequent official communiques with General Secretary Khrushchev, and directed an unofficial communication channel be established through his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, with the Soviet ambassador to the United States. But in the fall of 1983, Washington and Moscow were not talking.

On Sept. 3, 1983, a U.S. Navy EP-3 intelligence-collection aircraft was orbiting near the KAL 007 crash site when the Soviets wrongly determined the Navy plane had violated Russian airspace. Two MiG-23 fighters were ordered to shoot down the U.S. aircraft.

Gen. Charles L. Donnelly, commander of U.S. forces in Japan and the 5th Air Force, ordered a flight of four F-15s to intercept the MiG-23s. Simultaneously, 5th Air Force warned the EP-3 of the threat. The EP-3 pilot dove for the wave tops to evade the Russian fighters and after a tense period, the EP-3 reached Japanese airspace, safe from Soviet attack. As the F-15s completed their intercept of the MiG-23s, Donnelly ordered them to break off without engaging the Soviet fighters and to return to their combat air patrol orbit. When another general officer on the scene pointedly questioned Donnelly’s decision not to engage the MiGs, Donnelly responded, “I don’t think I’ll start World War III this afternoon.” [The author was an eye-witness to this exchange].

Maj. Gen. James C. Pfautz, the senior intelligence officer on the Air Staff—analogous to today’s Air Force A-2—supported the 5fth Air Force Intelligence analysis, which assessed that the Soviet shootdown of KAL 007 was a tragic mistake, not a deliberate act of murder. Pfautz prepared a briefing detailing his assessment that the Soviets had made a series of critical errors leading to the shootdown. But the Air Staff briefing failed to gain traction with the Intelligence Community leadership in Washington, including Director of Central Intelligence William J. Casey. In official Washington, the narrative that emerged was that the KAL shootdown was an intentional atrocity. On Sept. 5, in a nationally televised speech, President Reagan termed it “the Korean Airline massacre … a crime against humanity.”

In the days and weeks that followed, U.S. intelligence continued to analyze the event, eventually concluding that Air Force Intelligence had gotten the story right from the outset. While not absolving the Soviets of responsibility for the deaths of 269 people, the IC agreed that the shootdown resulted from months of hair-trigger alerts, fear of reprisals for not acting against a border violator, and confusion about the identity of the aircraft.

Yet at the highest levels, competing American and Soviet narratives became entrenched, and the battle lines were drawn in Washington and in Moscow. Secretary of State George P. Schultz gave an impassioned presentation before the United Nations Security Council, during which he presented classified evidence of the Soviet attack on KAL 007, raising global tensions to a fever pitch.

Weeks later, early on the morning of Sept. 27, the USSR’s National Missile Defense Center received warnings from its new missile detection satellites that the United States had launched intercontinental ballistic missiles from Grand Forks Air Force Base, N.D. (one source cites F.E. Warren Air Force Base, Wyo.). The Soviet watch commander that night, Lt. Col. Stanislav Petrov of the Air Defense Forces, was a signal processing engineer—not a typical watch stander—and he was subbing for a sick comrade. Petrov possessed unique knowledge of the strengths and flaws in the Soviets’ new satellite warning system, and assessed that the launch reports—which came in several, harrowing waves—must be false alarms. Petrov advised his leadership against a retaliatory attack.

Petrov—the accidental watch commander—was truly the right man in the right place at the right time. It took Soviet technical experts months to determine what went wrong that night. Eventually, they concluded that a highly unusual set of atmospheric conditions over the northern tier of the United States caused sunlight to be reflected off high clouds in such a way that the satellites’ sensors mistook the reflections as ICBM launches. Petrov had to make an assessment in minutes, not months. Had the Kremlin ignored Petrov and instead acted on the phantom American ICBM attack, the world would have been plunged into global nuclear war.

The Petrov incident remained unknown in the West until the late 1990s, after the fall of the Soviet Union. Word began to leak out as former Soviet officers felt free to speak and even write about the harrowing event. In a 2013 interview with the BBC, Petrov recalled how the monitors on his watch lit up with the warning first of a launch, and then and impending strike. First one missile, then another, and another, ultimately counting five incoming strikes. “There were no rules about how long we were allowed to think before we reported a strike,” he recalled. “But we knew that every second of procrastination took away valuable time; that the Soviet Union’s military and political leadership needed. And then I made my decision. I picked up the telephone handset, spoke to my superiors, and reported that the alarm was false. But I, myself, was not sure, until the very last moment. I knew perfectly well that nobody would be able to correct my mistake if I had made one.”

Unlike Donnelly, who would ultimately earn a fourth star following his deft handling of the KAL 007 tragedy, Petrov was punished for not following protocols; he was never promoted again. But he was eventually was awarded the Dresden Peace Prize and became the subject of a 2014 film, a documentary-drama, “The Man Who Saved the World.”

The final chapter of the war crisis occurred in November 1983. NATO had conducted a series of interlocking military exercises beginning that September, culminating in a nuclear war drill called Able Archer 83. It was designed to practice nuclear command, control, and weapons release procedures—including for the new generation of ballistic and cruise missiles being deployed to Europe. To the Able Archer exercise planners and participants, the drill was robust but routine. But to the Soviets, the exercise appeared to be a cover for a real nuclear first strike on Soviet territory. They reacted by placing their theater and strategic nuclear forces on, a system-wide Soviet nuclear forces alert of massive proportion.

Brig. Gen. Leonard H. Perroots, chief of intelligence for U.S. Air Forces, Europe (USAFE) at the time, noted the Soviet preparations and became deeply concerned. Briefed by Perroots, USAFE Commander Gen. Billy M. Minter considered whether to order a reciprocal nuclear alert. Perroots, fearing any such action would further inflame an already fraught situation, advised against it. Informed by deep knowledge of the Soviets, Perroots reasoned the smart approach was to de-escalate the situation by having U.S. forces do nothing unusual. The most dangerous moment came when Able Archer 83 reached its climax: a simulated request to the national command authority for nuclear weapons release.

Perroots urged his leadership to continue the Able Archer exercise, and to wind it down as if nothing unusual was happening across the Iron Curtain. Minter agreed.

Yet the full extent of Soviet preparations for nuclear war had not been understood by the Americans, and it took months to assemble the intelligence and create a complete assessment. Even then, there were disagreements within the IC about how close we had come to a nuclear conflagration. Nonetheless, Director of Central Intelligence Casey became convinced that we had nearly stumbled into a nuclear war and briefed President Reagan and the National Security Council principals accordingly. The President noted in a June 1984 diary entry how shocked he was to learn the Soviets believed the West was planning to launch a nuclear first strike.

The almost-complete lack of communication between Moscow and Washington had proved fertile ground for catastrophic miscalculation. In 1983, the two nuclear superpowers were like blindfolded boxers careening toward a death match. Almost no one on the U.S. side realized it.

Remarkably, however, the Soviet people were given a clue. Soviet Politburo member Grigory Romanov gave a national address in early November 1983, in which he described the geopolitical situation in dire terms. Soviet citizens were ordered to participate in civil defense exercises, including evacuations to nuclear fallout shelters in Moscow and other major cities. Factories, offices, and schools conducted civil defense drills. The Soviet General Staff canceled the annual fall employment of Soviet Army troops to help with agricultural harvests, keeping those forces in garrison instead. In East Germany, Soviet infantry units were sent to the field with two weeks of rations and ammunition loads, and Soviet Air Force fighter bombers in East Germany and Poland were loaded with nuclear weapons, a highly unusual action.

Soviet nuclear forces remained on varying degrees of alert through the early months of 1984. Andropov died in February 1984 and Operation RYaN wound down later in the year.

Perroots was promoted to major general and became the senior intelligence officer on the Air Staff, relieving Jim Pfautz. In short order, Perroots was promoted to lieutenant general, and he became director of the Defense Intelligence Agency in 1985. Upon his retirement, he wrote a classified end-of-tour report that recounted the events of the Able Archer 83 crisis from his unique perspective. His 1989 report prompted the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board (PFIAB) to launch a full-scale investigation of the 1983 events. The PFIAB’s report, which praised Perroots’ actions, was completed in 1990 and was finally declassified in 2015. According to the PFIAB study, General Perroots cited serious concerns about the inadequate treatment of the Soviet war scare by the Intelligence Community. The Perroots report itself was declassified by the State Department in February 2021, but after the CIA sued to have it reclassified, a federal judge ruled on Oct. 4, 2022, that it should indeed be reclassified.

Several lessons can be drawn from the near nuclear war of 1983 for leaders navigating today’s conflict in Ukraine:

Meaningful communication between adversaries is essential. It was present in 1962 and helped ensure war was avoided; it was lacking in 1983 and that absence nearly led to a nuclear war as a result. Absent such communication, it was left to the personal judgment of a few individuals to assess threats and risks and to have the courage to take prudent action.

Calm and patience are crucial. Donnelly understood when to apply pressure on the Soviets and when to withdraw it. He acted logically and did not allow his emotions or those of his senior staff to sway him. He patiently waited for situations to unfold, while taking appropriate action to be able to responsibly defend American interests, if necessary. When it was appropriate to deescalate, he didn’t hesitate to do so, despite some advice to the contrary.

Knowledge of the enemy and of your own forces is critical. Colonel Petrov knew it was highly unlikely that the United States would launch a nuclear first strike with a handful of ICBMs from one Air Force base. He understood that an American strike was more likely to be a general onslaught, designed to overwhelm the Soviets. Petrov used his expertise of the strengths and weaknesses of the USSR’s surveillance capabilities to assess incoming reports from all available sources rather than relying on satellite collection alone. Likewise, Perroots relied on his experience and gut in response to the Soviet reaction to Able Archer 83. His commander, in turn, trusted Perroots’ judgment and experience.

Mirror imaging of one’s adversary is extremely dangerous. The commonly held view in Washington during the crisis was that the Soviet leadership could not possibly believe that NATO would launch a nuclear first strike. The notion seemed patently absurd and was widely discounted. As a result, the IC downplayed numerous indicators of a massive Soviet nuclear alert. ‘Groupthink’ took hold in Washington in 1983 and the 1990 PFIAB report charged that it inadvertently put “our relations with the Soviet Union on a hair trigger.

As grave as the stakes were in 1962, they were far greater in 1983. By then, the size and capabilities of U.S. and Soviet nuclear forces dwarfed those of 1962. Had both sides’ nuclear arsenals been fully employed in 1983, nuclear Armageddon would have been inevitable. It was only the expertise and judgment of Air Force general officers, in Japan, in Washington, and in Germany—and the similar expertise of a Russian lieutenant colonel—that brought the world back from the brink of a nuclear war.

Confronting Russia’s current nuclear threats requires knowledge of the adversary, active communication, sound judgment, and the courage to make tough decisions that prevent escalation. By saying “this is not a bluff,” Putin demonstrated classic brinksmanship—an example of the Russian doctrine of “escalate to deescalate.” A firm, yet measured response is required, one that offers Moscow off-ramps to enable it to withdraw from the brink. If Putin believes backing down creates an existential threat to his regime, he will be less likely to compromise.

Today, as in 1983, open communication between Washington and Moscow is too rare. As of October 2022, Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin and his Russian counterpart, Minister of Defense Sergei Shoigu, have spoken only twice since the Feb. 24 invasion of Ukraine. History suggests more frequent contact would be prudent.

Brian J. Morra is a former Air Force Intelligence officer and retired senior aerospace executive. He is the author of the historical novel, “The Able Archers,” published by Koehler Books, which dramatizes the real events of the 1983 Soviet war scare. The Able Archers has been optioned by Legendary Entertainment to create a feature film or television series. An audio book was recently released by Blackstone Publishing. Learn more about The Able Archers at www.brianjmorra.com.