Why America’s Next-Generation Bomber Is Crucial to

Deterring Both Conventional and Nuclear Conflict.

The ability to conduct long-range strikes at scale in all threat environments has been a decisive U.S. military advantage for more than 70 years. Long-range bombers enable theater commanders to strike enemy targets inaccessible to other U.S. and allied forces. Yet this advantage is severely diminished today by a smaller bomber force that cannot meet growing demand for global precision strikes, in particular the contested environments we can anticipate in potential peer conflicts.

The Air Force’s B-21 Raider will be the world’s most advanced stealthy bomber when it is fielded later in this decade. For Air Force leaders, the challenge will be to fund the B-21 program to rapidly acquire the inventory it needs to meet operational demands. The Air Force cannot afford to repeat the cuts, delays, and outright cancellations that struck the B-2, F-22, and F-35A over the past three decades.

The U.S. will need a significantly larger bomber force than it has today. Without the Raider, the U.S. has no viable “Plan B.”

To achieve the capacity to simultaneously defeat Chinese aggression in the Indo-Pacific, credibly deter an opportunistic aggressor a in second theater, and still deter nuclear attacks on the United States—all requirements of the 2022 National Defense Strategy (NDS) —the U.S. will need a significantly larger bomber force than it has today. Even a delay in achieving this objective could result in a hollow U.S. military incapable of prevailing against China. Other combat aircraft lack the B-21’s attributes, and they cannot match the options B-21s offer theater commanders.

Without the Raider, the U.S. has no viable “Plan B.”

Today’s Bomber Force

In 1989, the Air Force had 411 B-52, F-111, and B-1 bombers in a force sized to deter nuclear threats and fight conventional conflicts against Cold War adversaries including the Soviet Union. This force enabled the decisive response that defeated Iraqi forces and sent them fleeing back home from occupied Kuwait in 1991. B-52s alone flew 1,741 combat sorties and dropped 27,000 tons of weapons on Iraqi targets in Operation Desert Storm—30 percent of all weapons, by tonnage, delivered by American airpower. Seven of these sorties flew directly from Barksdale Air Force Base, La., to strike Iraqi power and communications nodes on the first night of the air campaign. These sorties, called Operation Senior Surprise by the Air Force—or “Operation Secret Squirrel” by the crews that flew them—unambiguously demonstrated the ability of long-range bombers to strike any target on the face of the Earth.

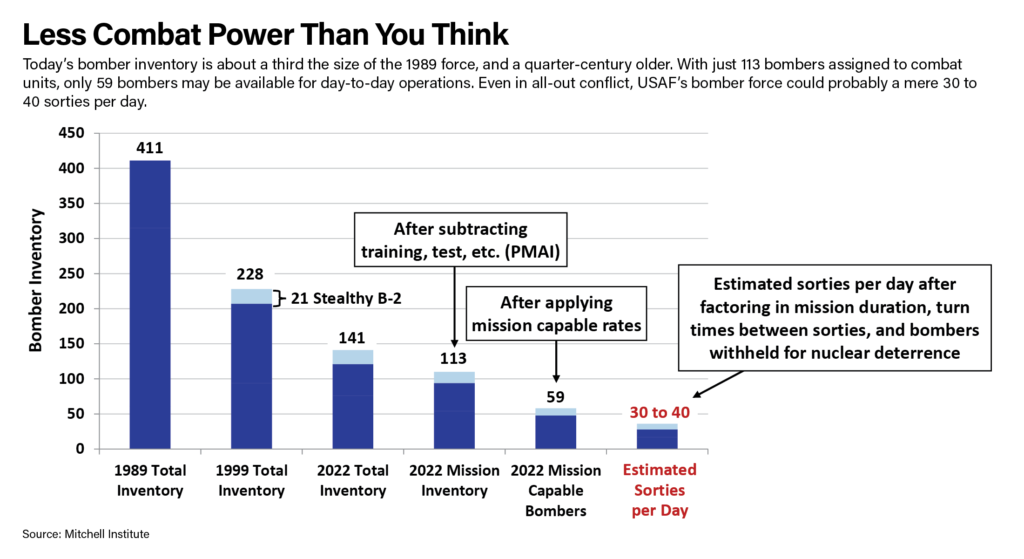

Despite their proven effectiveness, 30 years of cuts have reduced America’s bomber force to just 141 aircraft, most of which are the exact same airframes—B-52Hs and B-1Bs—that were on the ramp in 1990. Throughout the post-Cold War period, multiple Department of Defense reviews repeatedly downsized the combat air forces; labeled as “strategic” reviews, most of these assessments were, in fact, budget drills, driven by the objective to realize cost savings for other needs. The U.S. repeatedly traded current force capacity in order to sustain and upgrade remaining forces.

Today’s bomber force is also the Air Force’s oldest ever. The last new B-52 was delivered when President John F. Kennedy was in office; the Air Force took delivery of its B-1Bs in 1989. The Air Force plans to operate its B-52s until 2050, by which time they will have reached an unprecedented average age of 82 years.

DOD’s only long-range strike aircraft capable of penetrating contested areas protected by advanced integrated air defense systems (IADS) are its 20 B-2 bombers. Yet even that number is an overstatement: Only 16 of the 20 B-2s are assigned to combat squadrons; the other four are unavailable due to maintenance or testing requirements. Further, it is likely in any conflict that some nuclear-capable B-2s would be withheld from deployment to deter nuclear attacks on the U.S. homeland, especially during conflicts with a near-peer nuclear power. And because most flights would be long-duration missions across the vast expanses of the Indo-Pacific, B-2s would most likely average just 0.8 sorties per day or less.

In short, DOD’s long-range, penetrating strike capacity for a conflict with China currently totals jut six to eight B-2 sorties per day, depending on basing, sortie durations, and the time needed to turn aircraft between sorties. Losing a single B-2, whether in combat or some other reason, would reduce sortie potential by at least 10 percent.

This is the definition of a fragile force. The Air Force’s bomber inventory and other combat air forces are now too small, too old, and lack enough lethality and survivability for a peer conflict.

Three Decades of Cutting the Bomber Force

Over six quadrennial reviews, the Pentagon cut its bomber force in half. Plans now call for expanding the bomber force to meet new challenges.

| DOD Strategic Review | Bomber Force Sizing Decisions |

|---|---|

| 1993 Bottom-Up Review | 184 total bombers (100 bombers needed for one major theater war) |

| 1997 Quadrennial Defense Review | 142 operational bombers |

| 2001 Quadrennial Defense Review | 112 combat-coded bombers |

| 2006 Quadrennial Defense Review | Cut the B-52 force to 56 total aircraft (intent was to use resulting savings to modernize remaining bombers) Directed the Air Force to field a new stealthy bomber by 2018 |

| 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review | 96 primary mission aircraft New stealthy bomber canceled by the Secretary of Defense in 2009 |

| 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review | 96 primary mission aircraft (44 B-52H, 36 B-1B, 16 B-2) |

Why We Need Penetrating Bombers

Threats facing the United States and its allies and partners are now far different than the more benign security environment DOD used to justify hollowing out its bomber force in the decade after the Cold War. The dissolution of DOD’s long-range strike capabilities and capacity accelerated in the post-9/11 era, as resources were surged to fund low-intensity counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations.

While the U.S. cut, China invested. The People’s Liberation Army Air Forces’ most advanced weapons systems now approach—and in some instances surpass—the U.S. military’s capabilities. Further, China has fielded offensive and defensive capabilities “expressly designed to keep U.S. and allied forces at arm’s length and to suppress U.S. and allied operations for a period of time that is sufficient to allow the success of a fait accompli.”

China has developed an anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) complex that includes multiple variants of low-observable military aircraft, such as the J-20; the PL-15 long-range air-to-air missile, which has an active radar seeker and is carried internally by stealthy fighters; and other advanced weapons designed to intercept U.S. surveillance aircraft and air-refueling tankers, such as the 400-kilometer-class PL-XX. The Royal Uniformed Services Institute has suggested PL-15s can outrange U.S. AIM-120C/D air-to-air missiles, a standard munition used by Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps fighters for air-superiority missions.

China also has substantial inventories of the DF-21D anti-ship ballistic missile (ASBM), anti-ship and land-attack cruise missiles, and hypersonic weapons designed to strike U.S. bases and forces well beyond the first island chain in the Pacific.

China continues to modernize its nuclear forces and now has an operational triad of nuclear-capable intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM), bombers, and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBM). China’s growing nuclear warhead inventory suggests a shift from maintaining a minimum force designed to retaliate in the event of a nuclear attack on China to a force that equals or exceeds the U.S. triad.

In a conflict over Taiwan, China would be the “home team,” compared to the U.S. which would have to mount operations from a great distance away. That proximity means the PLA’s power-projection forces would be closer to mainland bases, with simpler resupply lines and greater protective cover from existing sensors and air-defense systems deployed along China’s coast.

China’s military modernization is on pace to enable it to potentially seize Taiwan by 2027 and become a “world class force” by 2049.

To counter China and defeat a Chinese fait accompli in Taiwan, the Air Force needs penetrating bombers that can deliver weapons at range, enabling theater commanders to achieve a wide spectrum of effects against the most difficult target sets. More Air Force long-range, penetrating strike capacity is now required to defeat Chinese aggression in the Indo-Pacific and meet other NDS force-sizing requirements. To a significant extent, the need for more long-range penetrating strike capacity is driven by theater commander requirements to counter China’s ’s operational advantages in a conflict that occurs along its periphery.

The long ranges required to project power against the PLA in the Indo-Pacific stresses the U.S. military’s current force design, which was optimized after the Cold War for lesser regional conflicts in far more confined and less-contested battlespaces. U.S. forces have grown accustomed to freely accessing bases near operating areas, surrounding those bases with forces, and then executing sustained, short-range operations with manageable risk, safe from enemy defenses.

Not so in the Pacific, where U.S. aircraft operating from Guam, northern Australia, and Japan must fly hundreds of miles to reach the battlespace around the Taiwan Strait and adjacent to China’s mainland. DOD’s current fixed-wing combat aircraft fleets overwhelmingly consist of fighters with a mission radius of 650 to 700 nautical miles (nm) or less, depending on their payloads and mission profiles.

To put this in context, 700 nm is like flying from Washington, D.C., to Tampa and back. The distance from Australia to the Taiwan Strait are more like flying from Washington, D.C., to Juneau, Alaska, and back—more than four times as far—and all in a single mission. Fighters operating from bases along the first and second island chains in the Pacific or from distant aircraft carriers would require aerial refueling to reach targets in the Taiwan Strait, and again to return to their bases. Critically, the PRC’s missile threats put carriers at risk, making them of little use in a defense of Taiwan scenario.

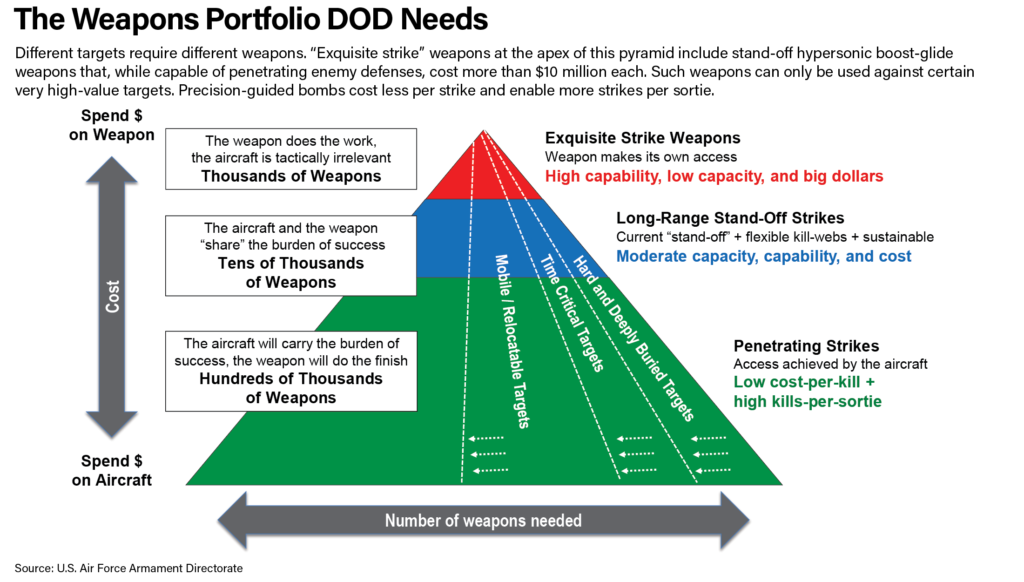

Long-range stand-off strikes are helpful, but not an alternative to penetrating bombers. Many of the forces that China would use for its initial assault operations, like SAGs and surface-to-surface missile launchers, will be moving or can quickly relocate. Highly mobile targets can significantly degrade the effectiveness of stand-off strikes. If all an adversary needs to do to be survivable is move targets a few hundred feet left or right, stand-off weapons won’t be enough to defeat them.

Only penetrating bombers have mission persistence to locate, track, and strike large numbers of mobile/relocatable targets in a single sortie. Compared to bombers, fighter aircraft carry fewer weapons and lack the range and loiter time to remain effective for long. Indeed, even in best-case scenarios, fighters operating from first island chain bases can reach parts of China’s coastline, but not much further.

What Penetrating Bombers Do

Penetrating bombers provide flexibility unmatched by other strike systems. The combination of long ranges, large payloads, on-board sensors, and other capabilities make penetrating bombers ideal for conventional strikes as well as suppression of enemy air defenses (SEAD), close air support (CAS), and other missions in all threat environments. With appropriate munitions, penetrating bombers can conduct maritime attacks and air-deliver sea mines deep into contested areas where surface ships could not operate. Maritime strike is already a key mission for the B-1 bomber, which can carry up to 24 Long-Range Anti-Ship Missiles (LRASM) per sortie.

Like other Air Force bombers, B-21s will be able to operate directly from the United States and overseas bases with less need for replenishment and aerial refueling compared to shorter-range aircraft and carrier air wings. This is crucial at the start of a conflict when Air Force tankers will be in extremely high demand to support deploying forces.

The B-21’s large weapons bays will also allow them to strike more targets per sortie than fighters, and their ability to penetrate highly contested areas will allow them to fire smaller, shorter-range weapons that are more effective against a range of targets. This increases the number and type of aimpoints that B-21s can strike per sortie compared to nonstealthy aircraft that must employ much larger stand-off weapons to strike the same targets.

Like the B-52 and B-2, the B-21 is designed to deliver nuclear as well as conventional weapons, making them “dual capable.” Bombers are the only leg of the U.S. nuclear triad that are able to be used for conventional or nuclear attacks. In a crisis, bombers can be postured to reduce their response times and dispersed to multiple bases to reduce vulnerability to counterattacks. As the most visible leg of the U.S. nuclear triad, bombers can launch, remain on airborne alert, and then recover or proceed on their nuclear strike missions, providing unmatched signaling options in a crisis.

Penetrating bombers are also the most effective means to strike mobile/relocatable targets. DOD has had a persistent shortfall in its capacity to strike large numbers of missile transporter-erector-launchers (TELs), surface-to-air missile (SAM) launchers, vehicle-based command and control (C2) centers, and other mobile and relocatable targets in contested areas. Mobilizing high-value targets has been widely embraced by the world’s militaries as a tactic to counter precision strikes. Today’s modern missile launchers can fire their weapons, stow their sensors, and relocate within minutes. For a cruise missile flying 400 nm to its target, even at high subsonic speeds, it can take more than 40 minutes from launch to impact. That gives mobile targets ample time to move.

Weapon flight times could be even greater for surface-to-surface missiles launched from more distant locations along the Pacific’s first island chain or Navy ships standing off 1,000 nm or more from China’s coastline defenses.

Another proposed approach is to design individual weapons with sophisticated sensors and the ability to loiter in target areas to find, identify, and then attack mobile targets. While valuable, such features drive up weapons costs to the point where they may be unaffordable at the scale needed for peer conflict. Weapons with a powerplant, capacity to carry enough fuel to fly long distances and then loiter, control surfaces to maneuver, guidance systems, and target seekers can cost millions of dollars each. Such costs are difficult to justify for all but the highest-value targets.

By contrast, penetrating bombers are reusable sensor-shooter nodes that can organically close kill chains against mobile/relocatable targets in contested airspace. This is a huge advantage over stand-off strike systems that depend on off-board sensors for target cues, especially in contested areas where space-based sensors and long-range data links may be degraded or denied. Smart munitions are no longer smart when they lose necessary data inputs.

The compressed kill chains of penetrating strike aircraft can also reduce the time available to an adversary to counter attacks. Compressed kill chains that improve the probability that PGMs will reach their designated aimpoints could also reduce the total number of weapons and sorties needed to strike large target sets. This is critical at the onset of a campaign when time and resources can make the difference between success or failure.

Penetrating bombers are the best means to strike very hard/deeply buried targets over long ranges. Killing hardened targets like aircraft shelters, C2 centers, and weapons storage facilities, typically requires large, hardened warheads specifically designed to penetrate through layers of concrete and steel. Destroying the most hardened and deeply buried targets requires extremely large penetrating weapons, like 5,000-pound “bunker buster” bombs or 30,000-pound GBU-57A/B Massive Ordnance Penetrators (MOP).

Cost-effectiveness is even more apparent when bombers are compared to long-range surface-to-surface launchers. As a rule of thumb, a PGM’s cost correlates with its range, technical sophistication, and launch mode. So a short-range, air-delivered JDAM with a simple GPS guidance unit costs tens of thousands of dollars; a more sophisticated mid-range Small Diameter Bomb II glide weapon costs about $200,000; and a powered JASSM-ER with a range exceeding 500 nm costs about $1.2 million. By comparison, surface-to-surface weapons require much larger rocket boosters to accelerate them from zero altitude and speed into ballistic trajectories, increasing the size and cost of such weapons. The Army’s surface-to-surface Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW) apparently has the range to launch from Guam and reach targets along China’s coastline, but at a cost of $50 million or more each, that’s an awfully expensive way to destroy a single target.

Crewed-Uncrewed Teaming

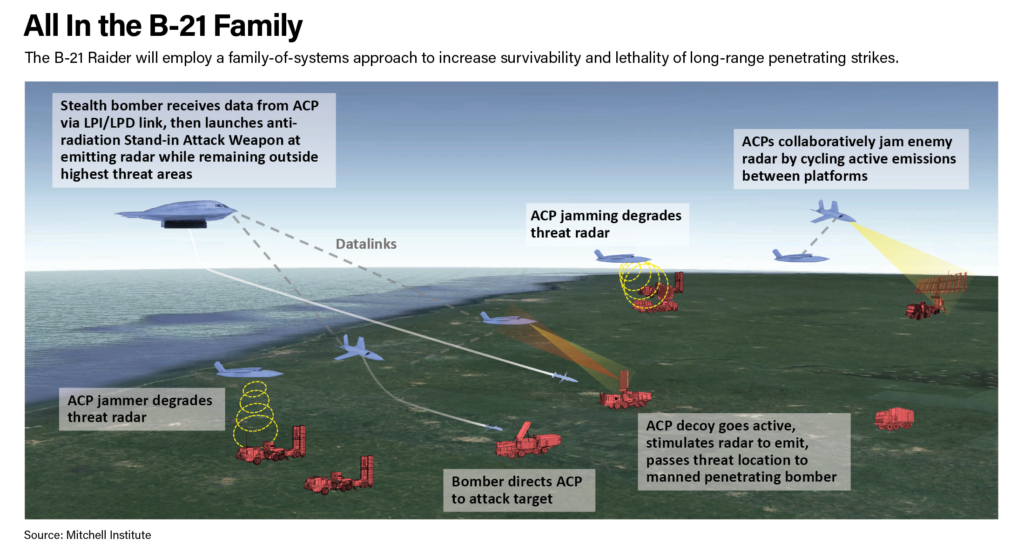

With advanced computing and sensors, B-21s will help usher in an era of crewed-uncrewed teaming, operating with collaborative combat aircraft at scale. B-21’s family-of-systems force design creates opportunities for the Air Force to use next-generation UAVs in new ways, increasing the B-21’s survivability and lethality. Penetrating bombers could be accompanied by or even carry AI-enhanced autonomous collaborative platforms (ACPs) that could locate targets—including moving targets—and pass cues to B-21s without the need for the stealthy bombers to use their own onboard radars or emit other detectable energy. Other ACPs could act as jammers or otherwise emit to stimulate enemy defenses to react in ways that can be detected. A bomber crew could then suppress or maneuver to avoid these threats

B-21s could also act as long-endurance information gateways, ISR nodes, and even “quarterbacks” for ACPs that are distributed across large areas. Unlike single-seat fighters, multi-crew bombers would have greater human cognitive capacity to perform as airborne ACP battle managers in combat environments. In combination, these attributes will make crewed bombers—not just ACPs—force multipliers in future teaming operations.

Notably, in order to maximize the capability that its future fleet of penetrating bombers and fighters could offer, DOD must also develop a new family of precision-guided munitions. These new PGMs should be designed to overcome advanced IADS that are increasingly capable against individual munitions like nonstealthy cruise missiles and even fourth-generation aircraft. Ensuring weapons are survivable maintains efficiency; otherwise, it takes more PGMs—and aircraft sorties—to attack and destroy each target set.

Sizing the Future Bomber Force

Today’s bomber force of 141 total aircraft can theoretically generate up to 59 sorties per day at the start of a conflict. The reality, however, is significantly less, since nuclear-capable B-2s and B-52Hs would almost surely be withheld to deter nuclear attacks on the U.S. homeland.

A deployed bomber might only be able to generate an average of 0.7 to 0.8 sorties per day or less depending on its air base location, mission duration, and the time needed to regenerate for its next sortie. Realistically, that suggests the entire bomber force might generate only 30 to 40 sorties per day. This will not provide the penetrating strike capacity to rapidly blunt and then defeat a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. Nor does it address the potential need to replace bombers lost in combat.

Sizing the Air Force’s bomber inventory and other combat air forces today for a single peer conflict, as the NDS requires, increases the risk that other opportunistic adversaries could open a second front, draining resources from the primary fight. Given China’s hegemonic ambitions in the Indo-Pacific, Russia’s initiation of the largest conflict in Europe since World War II, Iran’s nuclear and regional ambitions, and North Korea’s growing inventory of long-range missiles, the risk of an opportunistic second war is significant. DOD cannot expect the defense industry to rapidly rebuild force capacity as a hedge against a second conflict during a crisis. Because of the time it takes to train and supply ready forces, the Air Force must instead size those forces to reduce this risk. To be credible as a deterrent, the U.S. bomber force needs the capacity to simultaneously fight in the Pacific and respond to aggression in Europe or another theater.

Nuclear deterrence layers additional requirements on the number of bombers needed. The NDS requires the Air Force to size its bomber force to deter or respond to nuclear attacks even while engaged in a conflict. But here, too, there are new twists: In the past, the U.S. sized its nuclear forces to deter a single nuclear peer adversary. Today, however, China is emerging as a nuclear peer, joining Russia, and North Korea and Iran are also threats. Russia never stopped modernizing its nuclear forces and has now withdrawn its participation from all nuclear treaties. China is in the midst of a rapid nuclear build-up that could create a force of at least 1,000 warheads by 2030, according to Commander of U. S. Strategic Command General Anthony J. Cotton.

Dual-capable B-21s would be the most cost-effective means of quickly increasing the size of the U.S. triad compared to expanding the Air Force’s ICBM fields or acquiring additional Columbia-class submarines. Expected to make first flight in the coming months, B-21s will be flexible assets, able to support global operational requirements or go on nuclear alert in the event of a crisis. The alternatives are single-use systems. Moreover, each nuclear-capable B-21 would count as a single warhead if New START warhead counting rules were applied to future arms control agreements. No other alternative offers this “two-for-one” advantage or has the same potential to hedge against the uncertainty that spans the spectrum of conflict.

Another sizing consideration is that top Air Force leaders have already indicated a need for growth beyond 100 B-21s. Gen. Timothy M. Ray, former commander of the Air Force Global Strike Command, concluded that the Air Force must have 225 total bombers including B-52s to support the NDS and its single war force planning construct, and then-Chief of Staff of the Air Force Gen. David L. Goldfein testified to Congress that “a moderate risk force is 220 bombers of which 145 would be B-21s.”

Other studies have proposed an even larger bomber force. An independent study required by the 2018 NDAA recommended the Air Force field up to 24 bomber squadrons (383 total bombers) based on its assessment of forces needed to defeat Chinese and Russian aggression nearly simultaneously. Recent studies led by the Mitchell Institute have recommended the bomber inventory include at least 300 aircraft, including 225 or more B-21s.

Recommendations

1. DOD should increase the range and payload capacity of its strike forces for peer conflicts. DOD’s past decisions to retire two-thirds of its bombers created a combat aircraft inventory barely large enough for conflicts against lesser regional adversaries. DOD now requires much greater long-range strike capacity to defeat Chinese aggression in the Indo-Pacific and deter other threats as directed by the NDS.

2. A Total Force of more than 300 bombers including 225 stealthy aircraft is needed to provide the penetrating strike capacity needed to defeat peer aggression. Overwhelming strikes to rapidly attrit warships, armored vehicles, missile TELs, and other PLA offensive weapons will be critical to defeating a Chinese invasion of Taiwan and aggression elsewhere around the world. Only bombers can deliver warheads large enough to defeat very hard or deeply buried shelters, C2 centers, and weapons storage bunkers deep in China’s interior.

3. Developing a force capable of conducting long-range strikes at scale will require DOD to prioritize cost-effective capabilities. Defeating a Chinese invasion of Taiwan or another area it seeks to dominate may require U.S. forces to strike 100,000 or more aimpoints—too many to rely primarily on high-priced one-time-use missiles launched from stand-off ranges. Stand-off strike platforms require target cues from off-board sensors, secure data links, fire-control systems, and other capabilities that increase the complexity and expense of their kill chains. DOD analyses that have considered these and other factors repeatedly conclude that penetrating bombers capable of organically finding, tracking, and attacking multiple aimpoints per sortie are the more cost-effective means of striking large target sets over long ranges in contested areas.

4. A larger bomber force would be the most cost-effective means to deter two peer nuclear adversaries. Today, Russia’s nuclear forces are more modern than the U.S. triad, and China is increasing the size and capabilities of its nuclear triad to reach or exceed parity with the U.S. Only the expansion of the dual-capable B-21 force offers a “two-for-one” cost benefit with the potential to offset the growing threat from two near-peer nuclear adversaries.

5. A robust, faster B-21 acquisition rate is critical to deterring Chinese aggression. The PLA may be prepared to forcibly reunify Taiwan with the Chinese mainland before the end of this decade. This timeline coincides with the Air Force combat air forces reaching a new low in size and scale. Maximizing the B-21’s acquisition rate is necessary to manage costs and achieve objectives quickly. The Air Force must remain wary of a “buy-to-budget” approach, rather than advocating for additional funds to buy what is needed. Throttling B-21 acquisition to achieve short-term budget savings will increase program costs in the long run.

Col. Mark Gunzinger, USAF (Ret.) is the director of Future Concepts and Capability Assessments at The Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies.