The Civil Reserve Air Fleet is almost as old as the Air Force. It’s still going strong.

In a potential fast-moving future conflict, spread widely across the Pacific, the U.S. would depend on mighty Air Force C-5 and C-17 airlifters to move vast amounts of military materiel. But they can’t do the job alone. Air Mobility Command’s 1,145 tankers and cargo aircraft will be augmented—as they have been for 73 years—by the Civil Reserve Air Fleet.

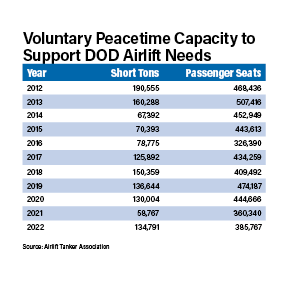

That fleet numbers some 441 aircraft belonging to 27 volunteer commercial carriers, and already carries more than 90 percent of the U.S. military’s passengers and 40 percent of its cargo on a daily basis. That includes everything from big equipment to small packages. The number of participants has remained above 25 for three years, and Transportation Command (TRANSCOM) is looking to add two more this year.

We’ve already seen a couple of our companies struggling with recapitalization, both in terms of the costs and availability, … [though] we are not expecting to lose any carriers right now.

—CRAF Program Manager David Atkinson

In exchange for day-to-day contracts to move people and cargo, participants in the Civil Reserve Air Fleet, or CRAF, agree to make aircraft and crews available to TRANSCOM in times of crisis. That means their airplanes and flight crews can, in effect, be “drafted”; if enough carriers fail to step up, the military can order an activation.

The first CRAF activation came during the Berlin Airlift, and only a few major activations have occurred since: Operation Desert Shield/Storm in 1990-91; Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003, and the 2021 evacuation of U.S. and coalition personnel from Kabul, Afghanistan.

Following that last chaotic evacuation, TRANSCOM questioned whether CRAF needed an overhaul. But a 2023 study concluded “the current setup of the program is sufficient,” said David Atkinson, CRAF program manager at Transcom, in a July interview.

CRAF was born in the 1950 Defense Production Act, at the dawn of the Cold War. Today, a quarter-century after that conflict ended, the U.S. is again competing with a peer rival, in China, as well as other challengers around the globe. The question of how many aircraft are available remains open, Atkinson noted.

“There might be a requirement for increased capacity, depending on how the enemy evolves and emerges,” he said. There could also be some adjustment to the “stages” of CRAF—each of which calls up a portion of the fleet, depending on how serious the crisis is—“and the configuration of the aircraft.”

A classified Mobility Capabilities and Requirements Study (MCRS) defines the capacity and makeup of CRAF every five years. The last MCRS was completed in 2020, and changes are likely in the next iteration, which will be conducted in 2025, Atkinson said.

The MCRS is coordinated with the Pentagon’s Cost and Program Assessment shop and TRANSCOM’s Joint Distribution Process Analysis Center.

“They do an extensive analysis, based on the most stringent threat,” Atkinson said. The last version included “Great Power Competition” scenarios, and the existing program, which calls for a minimun of 256 “wide-body equivalent” aircraft. “We have more than that in the system now,” Atkinson acknowledged.

CRAF demands fall into three categories:

- Stage I for “minor regional crises” and humanitarian/disaster relief operations;

- Stage II for major theater wars; and

- Stage III for national mobilizations.

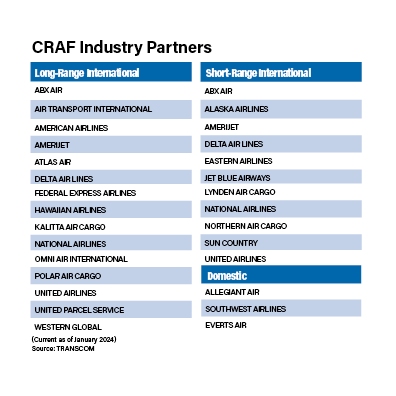

Operational needs for passengers and cargo are further divided into long-range international, short-range international, and domestic requirements.

The long-range international segment comprises transoceanic aircraft to augment AMC’s long-haul C-5 and C-17 airlifters, while short-range international supports requirements for nearby and intratheater airlift. Cargo craft must be fitted with hardened floors and tie-downs to transport pallets and equipment

AGING FLEETS

Like the Air Force, CRAF participants are also flying increasingly aging air fleets, and aircraft makers are no longer building large cargo and passenger aircraft like the 747, a CRAF staple.

For commercial carriers, “costs are pretty large,” Atkinson said. “Those are large capital investments … with every single aircraft [costing] $150 million to $200 million.”

Many carriers postponed or canceled new aircraft during the COVID-19 pandemic, and only now that air travel levels are back to pre-pandemic levels are most of those orders being reinstated. “Some older [aircraft] … may be on their third iteration through different companies,” Atkinson added.

Meanwhile, Boeing delivered its last 747 freighter to Atlas Air last year. “So no more 747s are coming,” Atkinson said. Boeing still makes the 777 and Airbus sells the A330, “But those … capitalization costs are extreme,” Atkinson said, and even if a carrier did order 100 new aircraft, they would not “all show up at once.” Modernizing the CRAF therefore will take both time and money.

“I think we’ve already seen a couple of our companies struggling with recapitalization, both in terms of the costs and also availability,” Atkinson said. “Difficulties in manufacture, difficulties in quality and safety, and everything else are affecting delivery times for those new assets,” he added. “It affects bottom lines.”

TRANSCOM holds regular conversations with its CRAF carriers to ensure its needs are unambiguous and that it understands carriers’ challenges. The two sides are in final negotiations for the next CRAF contract, which is expected to be executed in October of this year, Atkinson reported. “We’re expecting full subscribership,” he said. “We’re not expecting to lose any carriers right now.”

More freighter aircraft are actually coming to the market, but they may not have the hard decks, cargo doors and other features CRAF needs. Aviation analyst Mordor Intelligence, in a mid-2024 study, noted “the rising preference of airlines to modify and update their old passenger aircraft” as “passenger-to-freighter conversions.” However these new-to-the market freighters will tend to “carry lighter, more voluminous cargo like e-commerce packages,” and not the heavier cargo needed for military movements.

The company assessed the world freighter aircraft market at $6.57 billion in 2024, and said it’s expected “to reach … $8.70 billion by 2029.”

No new incentives will be included, but the work itself appears to be a sufficient draw. Among the contracts available are the Next-Generation Delivery System—for small package delivery—and Global Heavyweight, which utilizes empty space on airliners. The General Services Administration City Pair Program and the Defense Travel System round out military contract offerings.

“We have a lot of incentives that are extended to the carriers, but we’re always considering” other business opportunities for them,” Atkinson noted.

AGILE COMBAT EMPLOYMENT

A new wrinkle for CRAF is the way the Air Force and Marine Corps deploy. Both services anticipate more distributed operations spread out among numerous bases instead of at the large megabases that defined the recent era. What the Air Force now calls Agile Combat Employment (ACE), a hub-and-spoke model that spreads smaller units out to increase complexity for an adversary, will require a logistics system to match.

“We have a good mix of both long-range and short-range aircraft,” Atkinson said. For locations with shorter runways and fewer support facilities, additional capacity exists in the Federal Aviation Regulation Part 135 community; which includes smaller fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters. They’re typically used to support “functional command” activities, such as medical evacuation, “casualty evacuation, airdrops, parachute training, and international partnership support missions,” but they can also execute “the last mile of the mission” when needed. Part 135 operators “help us meet the requirements in the more austere environments,” Atkinson said. “They usually have smaller lift capacity and are designed to meet that tactical need. They also operate under a different set of regulations.”

Part 135 operators “help us meet the requirements in the more austere environments,” Atkinson said. “They usually have smaller lift capacity and are designed to meet that tactical need. They also operate under a different set of regulations.”

Innovations in aviation suggest there could be long-term uses for new electric or autonomous aircraft for the CRAF mission, but Atkinson said TRANSCOM “has no concerted efforts” underway at this time. The Air Force has flirted with reintroducing seaplanes, particularly to support ACE operations, but Atkinson said “very little seaplane infrastructure exists for large-scale seaplane operations.”

By design, CRAF assets do not fly into high-risk areas. They land short of a battle zone and then unload materiel and troops to move by air, rail, or truck to their final tactical destination.

CRAF operations in support of the Ukraine resupply typically include five or six freighters landing in Poland each day, where supplies are off-loaded and moved by truck or rail to Ukraine.

“That number’s gone up and down, obviously, but you know, that’s about the sustained number that we ask for volunteers, and that’s … how much the commercial carriers have been supporting us day to day,” Atkinson said.

During the 2021 evacuation of Kabul, the Air Force held a several-times-weekly “CRAF summit,” in which briefings gave carriers a classified-level insight into the dangers they faced in different destinations.

The summits were reinstated after Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. “We knew we were going to need freighter capacity,” Atkinson said. “But we wanted to avoid an activation. … Activation is not necessarily a bad word, but it’s something we try to avoid, and we need to be very judicious with our carriers in order to not needlessly affect their business.”

Are There Commercial Tankers in the CRAF’s Future?

There is a “viable commercial market” for aerial refueling, with two companies now offering such services to military customers, TRANSCOM’s Civil Reserve Air Fleet (CRAF) Program Manager David Atkinson said, but CRAF does not at this time contract with them. That could change, however.

Retired Gen. Mike Minihan was still head of Air Mobility Command in July when he told Congress that AMC is looking at contracting for commercial air refueling, and even the possibility of selling recently retired KC-10s—now parked at the David-Monthan Air Force Base, Ariz., “Boneyard”—to commercial operators, to bolster the Air Force’s air refueling capacity.

“There’s enormous value in aircraft that have the potential to provide readiness in the commercial sector,” Minihan said, adding “the important first work has been done” along these lines. “The analysis on the oversight and the certification is what’s next, and we now have enough data to do that,” he said. The potential shortcoming of the idea is that AMC has to ensure “with commercial refueling, that we don’t decrement the readiness of those in uniform flying the tankers:” Meaning, he doesn’t want to cut into the organic force’s tanking activity so much that it could hurt tanker crew proficiency. The two commercial tanker companies, Omega Air and Metrea, service a number of military air arms, but they can’t refuel aircraft headed into combat.

Metrea acquired four retired KC-135 tankers from Singapore and 14 from France, and performed the first air refueling of an Air Force jet in the summer of 2023. Omega refueled an Air Force airplane in December of last year. The mothballed KC-10s were retired last year not because of their performance—the type achieved a mission capable rate of more than 80 percent in fiscal 2023—but because the Air Force needed to shed logistical tails to save money.

At the summits, carriers got “an outline of the overall operational requirement” and TRANSCOM asked for volunteers, Atkinson said. Five companies did so, and have sustained that effort since Feb. 20, 2022.

Resupply operations supporting Israel are similar. “We again had another summit in response to Oct. 7 in Israel. … We had our CRAF carriers come in, we again gave them a classified briefing, gave them an update, and said, be prepared to volunteer. And we were able to avoid activation for that contingency as well,” Atkinson said.

More transparency is still needed. To sustain operations and enhance communications, efforts have included “adoption of mission collaboration communication tools, distribution of essential communication equipment, and robust engagement from tactical-level exercises to executive-level working groups,” Atkinson said. Stakeholders support these efforts, and “this strategy has already paid dividends. …We anticipate [it] will continue to strengthen the CRAF program.”

LOOKING AHEAD

Besides aging aircraft and geopolitical threats—“which lengthen routes, increase costs, and raise our carbon footprint,” Atkinson said—inflation is also a challenge. “It’s a constant hindrance to bottom-line profits for all carriers,” he said. “From fuel to labor costs—both pilots and maintainers, and salaries—these are a constant battle for them.”

Man-portable anti-aircraft defense systems pose a constant threat, but so far no CRAF carrier has been hit by such a weapon.

Atkinson said carriers have sought in recent years to reduce their crew sizes. The Air Force has not agreed, but TRANSCOM understands that the availability of experienced military pilots for commercial carriers has diminished.

“With the reduction in total military aircraft over the last two decades, and the commensurate reduction in the [Department of Defense] pilot force, the availability of ready-made and trained pilots for the commercial industry has declined,” Atkinson said. Yet because demand for commercial airline pilots continues to balloon, this “has the potential to exacerbate the problem.” At least for now, TRANSCOM is not doing anything to address the aircrew shortage.

“Commercial carriers bear an increasing level of responsibility to train their own personnel in-house,” he said.

In 2023, 72 years after its founding, the CRAF program was inducted into the Airlift Tanker Association Hall of Fame for “significant contributions to the advancement of air mobility.” The award marked the only program so recognized by the association. “CRAF is one of the longest enduring and best examples of industry and the government working together to offset a gap in capability and capacity at a low cost to the government,” the association wrote in a lengthy citation.

Atkinson said CRAF is regarded as successful, “but it’s a trust issue, right? We want to make sure that … these carriers continue to subscribe to the program.” He said his job, as the program manager, is to ensure “the health of the program remains intact, and a lot of that is through communication and through … very judicious use of the CRAF program overall.” Volunteerism will be encouraged because that “is how we avoid activation, quite frankly. And we will continue to do so,” unless a requirement emerges that outstrips the number of volunteers.